By Nigel Westmaas

“In August, during our school holidays, the cane fields in our village were harvested. A consuming expectancy claimed us all as, impatiently, we awaited the burning of the cane to remove the thick undergrowth, the impenetrable thrash which colonised the ground as the cane reached 12 feet or more. The aroma of burnt cane and scalded cane juice was seductive. It was a signal for our harvest to begin. The night before the cane was cut, in darkness or in moonlight, our reaping of choice, juicy stalks, provided sheer bliss through many hours of cane sucking, heightening the peculiar freedom stolen by boys in the night.” – (Clem Seecharan, Jock Campbell: the Booker Reformer in British Guiana 1934-1966)

Sugar, or ‘bitter sugar’, as Cheddi Jagan would compellingly describe it in a booklet, was central to the rise of the transatlantic triangular trade. According to conservative statistics, an estimated 40,000 ships conducted the grisly trade in the enslaved from the African continent. European ships brought manufactured goods to Africa, traded them for enslaved Africans, transported these individuals to the Americas to work on sugar plantations, and returned to Europe with sugar and other goods. This intercontinental trade was a crucial part of the early capitalist system—what Sven Beckert, author of Empire of Cotton, aptly terms “war capitalism.” This system’s viciousness led to wars of aggrandisement over land, the destruction of societies in Africa, primarily for sugar production, beginning in the 16th century.

Sidney Mintz, in Sweetness and Power, highlights the dual nature of capitalism that produced sugar. On one hand, it generated immense wealth and contributed to the material development of millions; on the other hand, it fuelled the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, wreaked environmental destruction, and, as one writer noted, led to “unhealthy consumption patterns” on a global scale.

The European demand for sugar profoundly influenced the world, playing a pivotal role in shaping modern global capitalism. Sugar was part of a broader system of exploitation and control of land, alongside other key commodities like salt, cotton, silk, tobacco, tea, coffee, gold, timber (and paper), and oil. Among these, sugar stood out for its significant economic, political, and cultural legacy, shaping the international economic system for over four centuries. As Vincent Roth noted in Timehri magazine: “throughout Europe, sugar continued to be a costly luxury and an article of medicine only until the 18th century when the increasing use of tea and coffee brought it into the list of principal food staples. Thus, in 1700 the amount used in Great Britain was 10,000 tons; in 1880 it had risen to 150,000 tons, and in 1885 the amount used was well over a million tons.”

In Guyana’s case, sugar has been more than a commodity; it has been the foundation of the nation’s economy, politics, social structure, and cultural identity throughout its history. From the early colonial plantations that fuelled the horrific trade in Africans to the rise of powerful sugar barons and later companies, who wielded immense influence, the story of sugar is deeply intertwined with Guyana’s economic journey through centuries of change.

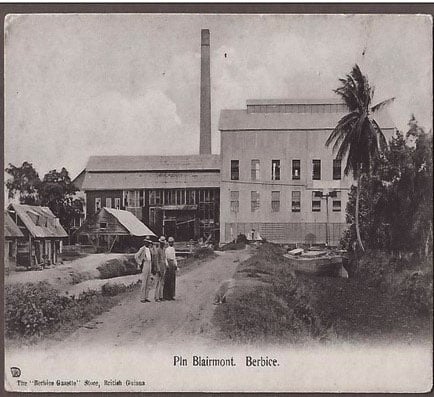

However, the traditional factories, economies of scale, and vast fields that once dominated industry are no longer prominent today. The number of sugar factories (former plantations) has decreased from a high of about 120 plantations in the late 19th century to four today.

Sugar in Guyana – its historical roles

As elsewhere, the history of sugar production in Guyana is a story of colonial exploitation and economic development, as well as an array of cultural expressions and resistance. However, sugar is not the only crop with such a legacy in Guyana. Cotton and coffee also played pivotal roles at various points in history. Like sugar, these crops fuelled the machinery of slavery and economic disparity, leaving indelible marks on societies and economies.

Sugar cane was a notably demanding crop. Environmental factors such as weather patterns, soil fertility, and pest infestations posed significant challenges to sugar production, requiring those in exploitative control, like global capitalism everywhere, to continually adapt their methods to maintain output and profitability.

From the start of sugar production in Guyana in the 1630s until emancipation in 1838, Africans and African Guianese were forced to labour on sugar plantations (and in other forms of labour) for approximately 210 years.

We can assess Guyana’s political and economic decision-making experience in sugar production through several broad phases. The first phase, from the 1640s to 1740s, was marked by near-total Dutch monopoly dominance. The second period, from the 1740s to 1814, was characterised by dual control of the Dutch and British, with the Dutch maintaining political control and the British beginning to dominate economically by the early 19th century. The third phase began with the British takeover from 1815 until emancipation in 1838, as tensions between slavery and free trade capitalism became more evident.

Meanwhile, powerful planters’ lobbies and law offices worked to protect the interests of those who controlled sugar production. Insurance companies, merchant clerks, and banks played crucial roles in financing and securing the often-risky business of sugar cultivation and trade. The importance of the sugar trade was frequently debated in political legislatures, highlighting its profound impact on both national and international economies.

In “A Voyage to the Demerary,” Henry Bolingbroke described the typical plantation in Demerara-Essequibo as a “curious mixture of European industry, arithmetic, and frugality, with a Caribbee indifference to luxury, grace, and accommodation.” From all indications, he was coupling the character of the plantation owner with the nature of the land and the mobilisation of finance and technology to achieve the eventual outcome, profit.

Reportedly, the first sugar estate on the east coast was Plantation Kitty. In 1797 George Pinckard stated that the “windmills of Plantation Kitty afforded a landmark for ships making the Demerara River, the estate being the only one on the East Coast growing sugar, all the other hundred and fifteen plantations in the area being then under cotton.”

By 1846, there were 35 sugar estates along the coast. According to historians Da Costa and Higman, “in 1810, 58% of slaves worked on sugar estates, 10% on coffee, 20% on cotton, and another 8% on urban activities.” The large involvement of enslaved people in the Guianese economy raises the issue of unrest and its impact on sugar production. One of the largest enslaved rebellions in the Western Hemisphere occurred in 1823 in Demerara.

In his remarkable edited collection Guyanese Sugar Plantations in the Late Nineteenth Century, Walter Rodney provides notes from the Argosy newspaper, covering approximately 120 estates during the identified period, with brief descriptions of each.

The world-famous “Demerara yellow crystals,” as noted by Rodney were associated with the new vacuum pan technology of the late 19th century. This product gained a high reputation as a ‘direct consumption’ or ‘grocery sugar.’ The premium price and popularity it enjoyed in retail stores in the United Kingdom during the 1880s and 1890s led to several attempts to fraudulently market other sugars as Demerara crystals.

The Booker family were prominent merchants based in Liverpool in the early 18th century, involved in shipping activities long before the official establishment of their firm. They played a key role in the trade routes between Britain and its colonies, particularly in Demerara, where they began their operations well ahead of formal company creation. In 1885, John McConnell, a significant figure in the business world, joined the Booker company. This partnership marked an important development in the company’s history, but it was not until 1900 that the firm’s name officially changed to Booker-McConnell, reflecting the growing influence of McConnell and solidifying the company’s place in the commercial landscape.

In 1834, when the abolition of slavery was declared by British parliamentary edict (along with generous “reparations” or kickbacks for the planters), Guiana was a colony progressively expanding its sugar production. This was in stark contrast to the other British colonies in the West Indies. Indeed, sugar production in Demerara, which really escalated from the 1740s, fast became the main colonial crop for all three counties. At the level of production sugar was clearly on the upward curve.

African emancipation came in 1838, and the plantation system attempted to retain African labour as they looked for labour elsewhere. As Walter Rodney opined, “the traditional interpretation is that this Black labour force then skipped the plantation. The evidence… is that the African people continued to work – in many senses they even intensified certain aspects of their work on the plantation. But they did so under conditions in which they now had, and began to put into practice, an alternative vision about the organisation of work, about their culture, about their politics and about what they expected in society.” In 1841-42 and again in 1848 there were sugar strikes largely by African Guyanese – strikes which Rodney deemed a major achievement: “black labour on the plantation…that only three years before had been described as persons dehumanised within the most fearsome social system we have known, were operating like a modern proletariat, making wage demands…for working conditions…and going on strike.”

While indentured workers came from Portuguese, Chinese, and African backgrounds, the largest group consisted of Indians from various regions of the Indian subcontinent. Between 1839 and 1917, approximately 239,000 Indians arrived as indentured labourers. Their arrival introduced new cultural and religious practices, significantly contributing to Guyana’s diverse identity. However, this period also saw resistance to the system of indentured labour, resulting in what Pulandar Kandhi termed “indentured insurgency.” These immigration patterns shaped Guyanese society, fostering the development of a multiracial, multiethnic population that included a working class and, later, a middle class across all ethnic groups.

Later developments in sugar

The harsh conditions faced by workers on sugar plantations led to the rise of labour movements and trade unions. Strikes and protests became common, playing a crucial role in the fight for workers’ rights and political change. The sugar industry has been central to numerous commissions of inquiry and legislative ordinances, as governments and stakeholders have sought to regulate and capitalise on its production and trade. One notable example was the Venn Commission, established in response to the shooting of the Enmore sugar workers in 1948.

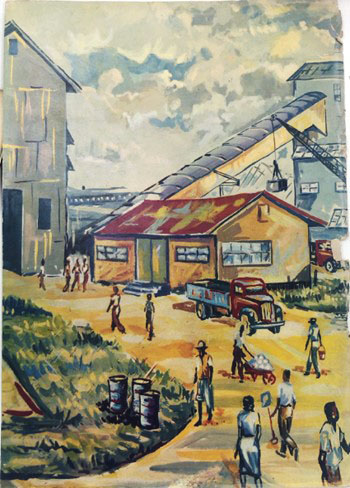

In the early 1950s, the sugar industry in British Guiana underwent consolidation, leading to the rise of a massive conglomerate, Bookers, alongside a few smaller companies that dominated the industry. By 1953, Booker Brothers, McConnell & Co Limited had become the parent company for several operating companies, the largest being Bookers Sugar Estates Limited, which managed 11 of the 15 major sugar estates in British Guiana.

According to Rodney, “Bookers used capital out of the sugar plantation for investment both in the economy outside of sugar, in the service sectors, in the light industrial sectors…” This was evident in the company’s reach in economic interests. Bookers had significant interests in the rum industry, Limacol, printing services, shipping and transport, insurance, wharves, stockfeeds, drug stores, travel agencies, petroleum agency representation, gold trading, and general stores.

Reform of the industry chronicled by Seecharan’s magisterial work on Jock Campbell examines the role of the individuals, who were instrumental in significant social reforms away from the monopolistic, uncaring hand of capital. These reforms included the development of spaces for leisure, amelioration of working conditions, technological improvements in the industry, cooperation with the Guiana state, among other initiatives inclusive of the development of the infrastructure for cricket.

Beyond its economic and political influence, sugar has inspired literature, poetry, and political oratory, fuelling social and scientific discussions about its role in shaping human history. Writers and poets have often used sugar as a metaphor for exploring themes of power, exploitation, and resistance, while political leaders have debated its implications for health, trade, and international relations. A noteworthy literary work that captures the spirit and struggles of this industry is the late Rooplall Monar’s “The Cane Cutter,” first published in the 1966 edition of the Chronicle Christmas Annual. Monar’s portrayal of the cane cutters offers a glimpse into the harsh realities of plantation life, including the physical demands and social injustices faced by the workers.

In the 1970s, the Government of Guyana nationalised the sugar industry, aiming to address social inequalities and improve economic control. The Guyana Sugar Corporation (GuySuCo) was established to manage sugar production and distribution.

Despite nationalisation, the sugar industry faced challenges, including fluctuating global prices, competition from other sugar-producing countries, and issues with productivity and efficiency.

In summary, sugar has been a central force in Guyana’s historical development. Sugar involved all these things and significantly influenced the coastal plain’s landscape and shaped the political environment, leaving a lasting mark on the country’s history and development for a long time but is now replaced by the emergence of the oil industry. Ulbe Bosma writes in The World of Sugar: “in the mid-nineteenth century, sugar was what oil would become in the twentieth: the Global South’s most valuable export commodity.” Oil, like sugar, will face the vicissitudes of the global capitalist system. It will also create enormous wealth and changes in social class arrangements (and the physical landscape) in Guyana. More importantly, to borrow from Alan Adamson’s evocative note on sugar, oil will correspondingly face the “simultaneous processes of growth and decay” that will be inevitable with the still powerful global capitalist “war” system that prioritises enormous profits over the earth, seas and human development.