Lengthy periods rarely go by these days without one of more readable articles on Guyana appearing in one or another section of the international media. These, frequently, depart radically from the ‘Banana Republic’ themed pieces, virtually the only types of reportage on the country that used to appear in sections of the global media. If the issues that spawned the controversial pieces are far from non-existent these days, those, for the most part, have become subsumed beneath the rags to (potential) riches pieces that appear in the international media on a country that foreign journalists had previously taken to describing as a ‘banana republic’.

The banana republic scenario commonly embraced themes that included rigged elections, ethnic tensions and dire poverty, among others. If those themes are yet to disappear entirely from international reportage on Guyana, oil and its prospects for social, economic and (perhaps even) political transformation are now numbered among favoured journalistic ‘offerings’ on Guyana by sections of the international media.

One of the more recent pieces, an article titled ‘Oil boom in Guyana: The world takes notice of one of Latin America’s smallest nations’ published in a Swiss/German language daily newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) has shifted the narrative to projecting Guyana simply as “one of Latin America’s smallest nations with 15 billion liters of oil lying off its coast.” Possessed of its new-found petro credentials, the article says, “Guyana now wants to play a bigger geopolitical role in the global theatre.”

One of the more recent pieces, an article titled ‘Oil boom in Guyana: The world takes notice of one of Latin America’s smallest nations’ published in a Swiss/German language daily newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) has shifted the narrative to projecting Guyana simply as “one of Latin America’s smallest nations with 15 billion liters of oil lying off its coast.” Possessed of its new-found petro credentials, the article says, “Guyana now wants to play a bigger geopolitical role in the global theatre.”

In much the same manner that, not many moons ago, international media houses had to comb their way through a thicket of negatives to unearth scraps of pleasing narrative about Guyana, these days, both global powers and regional partners like member states of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) are drawing closer to Guyana. For its part, Washington, these days frequently refers to Guyana as a ‘strategic partner,” while China too is expanding its presence here through investments. The pleasing narrative persists, making reference to the country “working on regional initiatives like a road link with Brazil” and aiming “to be a leader in rainforest conservation.” Oil, it seems, has significantly rewritten the country’s foreign policy narrative and now causes the international community to take the country more seriously.

If sections of the NZZ article appear to find it difficult to avoid repetition of the condescending narratives of a handful of years ago – “Guyana, a country in South America’s northern region is about twice the size of Germany but has a population smaller than Luxembourg’s”; “its parliament is made up of part-time members, and the nation’s highest court convenes in a modest wooden building”; “George-town, the capital, is home to just 200,000 people” – it parades a photograph of President Irfaan Ali with US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken as a ‘step up’ for Guyana, an acknowledgement by Washington of the country’s new-found petro credentials. The same ‘credential’ was bestowed on the Guyanese President following his 2023 visit to China following an invitation by President Xi Jinping.

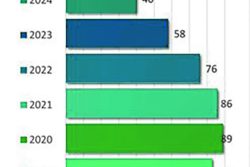

NZZ goes on to describe Guyana’s rise from obscurity to significance and the country’s ongoing transformation, for the most part, to five years of ‘tapping’ into Guyana’s “15 billion barrels of oil,” effectively “making it the third-largest oil producer in Latin America, behind Brazil and Mexico” and on its way to becoming a “global powerhouse.” Guyana’s oil discovery, the NZZ article states, positions the country as a “rival” to “Qatar’s production levels.” It goes on to add, pointedly, that “different countries are eyeing Guyana for different reasons, each pursuing its own strategic interests” whilst describing Venezuela’s recent significantly hyped up territorial claim as a distraction from what ought to be the diligent pursuit of growth and development that ought to derive from the country’s enormous oil resources.

Not a great deal in the hemisphere these days is seen outside the framework of strategic considerations. The reality here is that while Guyana’s new found ‘oil wealth’ may have lessened the historical pressures that arose from the country being seen (and referred to in the western media) as a ‘Banana Republic’, the country’s oil wealth does not reduce its other vulnerabilities, not least the constant threat by Caracas to annex a significant portion of the country’s land mass. In international circles the view exists that Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro is likely to play the ‘territorial integrity card’ at points in time in the future when it suits him. Some months ago the roar of a US fighter jet over Georgetown served as a poignant reminder that the Venezuela’s threat to further press its territorial claim is very real.

In effect, how to manage the country’s oil wealth in a manner that enhances its hemispheric and global image as an asset with which to help ‘manage’ what, recent developments suggest, is the Maduro administration’s determination to continue to strategically play the territorial claim card, an effort that will closely embrace the deploy of its petro resources to enhance its global socio-economic standing, is likely to be its most demanding mission in the period ahead.