Miranda Bernard, Marjorie Rodrigues and Helen Thomas, producers of Amerindian art and craft, cassava-based products and the popular potato wine also known as Fly are a few of the many women successfully using the traditional indigenous products they produce to earn a livelihood.

Bernard, who specialises in the production and sale of art and craft, and Rodrigues who produces, buys and sells cassareep are both single parents who have used the profits from the sales to help to educate their children.

Stabroek Weekend encountered these resilient women peddling their offers during the Ministry of Amerindian Affairs Cultural Extravaganza that included an art and craft exhibition, and sale of Indigenous beverages and foods held at the National Park tarmac earlier this month.

Miranda Bernard

Bernard, of Pakuri Village also known as St Cuthbert’s Mission, makes mats using tibisiri and other indigenous materials she finds. “I specialise in headdresses, headbands, necklaces, earrings, bracelets and foot-bands,” she said.

The profits from the sale of her craft are also helping her son who is now an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto in Canada.

She also buys and sells some other art and craft like placemats, fruit baskets, jewellery baskets, bread baskets, bottle holders among other things.

“I make my biggest sales at exhibitions like these,” she said, adding, “We also have a craft shop in the village where I put some of my stuff to sell. We give ten percent on the items sold to the craft shop.”

She also caters for individual orders. She noted that many people in the village are craft producers so that marketing of their products is competitive. She does not supply stores in the city because they want the craft way below the cost of production.

“The way I calculate my business, I factor in the materials, labour and transportation,” she said.

Bernard took over the craft production business from her parents after her father died seven years ago and her mother fell ill and is still recuperating. Her other siblings all pitched in their lot to assist with their mother’s recovery.

“Both of my parents took care of me and my son, Meschach Bernard, before my dad died, and my mom fell ill. They were self-employed. They did their own farming and made handicraft, and sold at exhibitions. They also reared poultry,” she said.

Bernard was a teenager at the time of her son’s birth. When her father died Meschach had just written the then Secondary Schools Entrance Examina-tions and secured a place at St Cuthbert’s Secondary School.

“Because of the environment at the secondary school, my son was not doing well,” she said. “My brother who lives in Canada suggested that I send my son to a private school to get a better education. He said education is the only investment to bring us out of poverty. He insisted on him going to a private school and to pay his school fees” she said.

Bernard decided to register her son at Camille’s Academy which was then known as Camille’s Institute, on the East Bank Demerara. Fortunately for Bernard, she has a sister who lives at Soesdyke, East Bank Demerara who undertook to take care of her son.

She related, “When I took his results from St Cuthbert’s Secondary, the head teacher of Camille’s said she could not put him into form one because his grades were too low.”

Meschach was placed in a remedial class and by the mid-term he wrote a test to determine whether he could join the form one class or continue in the remedial class and write the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC) examinations in his sixth year in school. He passed the test.

“Before I went back to Pakuri I had a good talk with him,” she said. “I told him to study hard. I told him if you have to write CSEC in six years time it would be hard on me. When he wrote the exams at mid-term he passed with over 60 per cent. After that Christmas term he started to climb up in his academic work. … His father, who lives in Canada, put in his papers which came through a few weeks before he was due to write 16 CSEC subjects for which he had signed up, mainly science. He left before writing the exams.”

In Canada, she said, Meschach scored 100 percent on his entrance exam to high school. In Grade 11 he continued scoring 90 to 100 percent.

He told his mother he studied late into the night because he wanted to do well and he knew the sacrifices she was making at home, including for himself. Bernard is one of seven siblings and is the only one living with her mother in the family home at Pakuri.

“I had to and still have to send him money to help him, and I do this from the profits I earn,” she said.

On leaving high school, Meschach, now 19, applied to several universities and many accepted him to specialise in different areas. However, he did not accept any because he was waiting for a reply from the University of Toronto where he had applied to study forensic science. That was the university of his choice. It was the last university he heard from. He is now a second-year student at the University of Toronto.

“His dad is in Canada, but he does not live with him,” Bernard explained. “He lives with my brother, the same one who had advised me to send Meschach to a private school. His father only helped to put his papers through to go to Canada. I am very proud of my son. He often says if it was not for his uncle insisting that he left Pakauri to attend a private school, he does not know what life would have had in store for him. And he would have never been in a university like he is today. He is proud of the foundation he got from Camille’s Academy.”

Meschach works part time on Saturdays and Sundays.

Marjorie Rodrigues

A native of Acquero, Santa Rosa Village, Moruca, Rodrigues markets one of the best, if not the best cassava cassareep, locally. It is marketed as Moruca Cassava Cassareep and could be obtained at the Ministry of Amerindian Affairs craft shop, Thomas and Quamina streets. Rodrigues, now 62, started selling cassareep about 44 years ago in order to ensure that her only child successfully completed teacher’s training at the Cyril Potter College of Education.

“My daughter was about 18 years old at the time. I started with one five-gallon bucket of cassareep which holds about 26 bottles (750-millilitres each) of cassareep. As a single parent with no other source of income I did that to ensure she had some money to buy the things she needed. I kept part of it to reinvest,” she recalled.

She continued doing this even after her daughter graduated from CPCE. Then she fell ill and had to stop.

“Then I had to return to it because there was no other means of income,” she added.

Before she started to supply the Ministry of Amerindian Affairs craft shop with cassareep, Rodrigues was supplying Shell Beach Adventures run by businesswoman/environmentalist Annette Arjoon whom she had met at the Ministry of Amerindian Affairs’ first art and craft exhibition that was held at Sophia.

“I used to make cassava biscuits at that time. I don’t do it anymore because it is too costly. I continued with the cassareep,” she said.

She began selling 26 bottles of cassareep, monthly, to the Amerindian craft shop which was then housed at the Amerindian Hostel in Princes Street, Georgetown.

“That wasn’t lucrative at the time. As time went by, and sales increase, things became better. That is how, today, I’m still supplying them,” she said.

The cassareep business has helped her to develop beyond her expectations.

“It has done quite a lot for me. I was able to build for my mother, who recently passed on, a proper house which I had promised her even though it’s not quite finished. I’m now in the home. I built it with the profits I made from the sale of cassareep,” she said.

Rodrigues travels between Moruca and the West Bank Demerara where her daughter resides to look after her business.

“I only have one child and she’s a teacher. I travel to do my own business because she cannot help me in certain areas,” she noted.

During the Christmas season, when people look forward to making their pepperpot, she said, “I am really busy and sometimes there is not enough cassareep to go around.”

She contends that her cassava cassareep is pure. “You can identify it by the smell and the taste,” she said.

She makes cassareep herself, but she buys most of it because of the amounts required.

“From 200 pounds of cassava you would get about one and a half bottle. And you will get nothing much especially if the cassava is dry which is good for cassava bread but not for cassareep. That is why I go out and buy but most times people come to me, and I buy from them,” she related.

To ensure her product is of good quality and because cassareep is not boiled over several days or a few weeks, as it was done in the past, Rodrigues boils the cassareep she purchases.

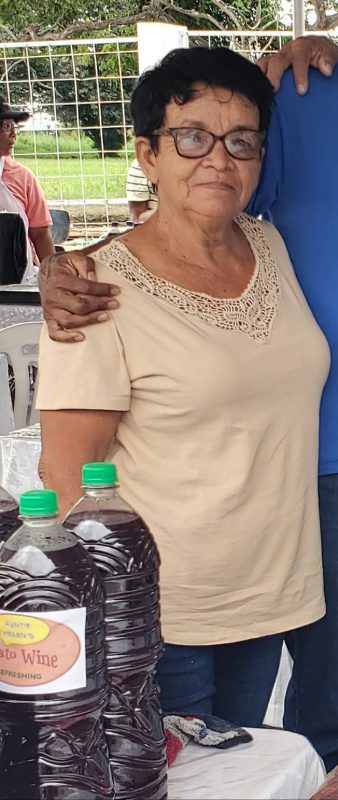

Helen Thomas

Thomas is well known at Amerindian Heritage Exhibitions for her Fly. She markets her wine as Auntie Helen’s Potato Wine.

Thomas, who makes her own wine, has been in the business for over 40 years.

“Former Amerindian Affairs Minister Carolyn Rodrigues encouraged me to sell the fly at an exhibition that was held at the Umana Yana in Kingston. That was where I first marketed my wine outside of Moruca,” she recalled. When the exhibition moved to Sophia, she had been selling Fly there every year since.

“I make my own Fly. After I learned to make Fly, I knew it was a good business. When you make a good product people go after it. Then I started to plant my own potatoes. I farm it myself and I get good results. The better the quality of potatoes, you reap, it’s a better drink you get,” she said.

She makes her Fly with the black sweet potatoes. “In Moruca we have the black sweet potatoes that gives the Fly that dark ruby colour,” she said.

She noted that other vendors sell a pink-coloured Fly which she opined is not “the real thing.

When I see the pink-coloured Fly at the exhibition I know they’re not getting the real potatoes like we get. It’s only people from Moruca make the really nice Fly.”

Asked how she learned to make the wine, Thomas said, “From my mom. She passed it on to me and I’m passing it onto my daughter-in-law.”

Asked how she makes it, she said, “You know there is always a secret to making the best beverages. I can’t share the recipe. I can tell you I boil all my water in making the wine and prepare the wine under very hygienic conditions because we don’t want people to get sick. We don’t want them to say it’s the Fly that made them sick.”

This year, she said, she was honoured to sell a five-gallon bucket of Fly to the Office of the President. Most of her customers, she said, are “my Moruca people” and other indigenous people.

“If the government or the Ministry of Amerindian Affairs can help us to market our products, that would be a great help to us. We are Amerindians all the time, not only in September,” she noted.

Last year at Sophia, some foreigners sampled the wine and later they bought several bottles to take away. “The wine lasts a very long time,” she said.

Mainly from the sale of Fly, Thomas has built her own house and furnished it.