In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket Roger Seymour recounts his search for an ailing former West Indies Test cricketer.

Prologue

Back in the mid-1970s to mid-1990s, whenever the West Indies were playing, a standard feature of the landscape was everyone’s radio tuned to the cricket match. Every passing vehicle blared live commentary. Lots of folks, mainly men, walked around with transistor radios plastered to their ears, and would immediately respond to any request for the latest score. Replies such as, “Two fifty for three, Richards on 88, we are in the driving seat,” were standard fare. However, the high quality broadcasts were more than a source of commentary, as audiences were constantly updated on all manner of subjects in between the action.

“We would like to say a special hello to the former West Indies Test bowler, Inshan Ali. Sadly, we heard that he is very ill in hospital and is unable to attend this Test match. We understand that he still maintains a keen interest in the game and he watches every ball of every match on the telecast, or, as in this instance, is listening on the radio,” the commentator had a distinctive Trinidadian accent. It was during one of the breaks of the Third Test between the West Indies and Australia, at the Queen’s Park Oval in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad. Scheduled for 21st – 26th April, 1995, the hosts won in three days by nine wickets, in a low-scoring affair on a grassy under-prepared pitch, to level the series. Scores: Australia, 128 & 105, West Indies, 136 & 98 for one.

…..

Hitting the trail

“Good afternoon, Caura Chest Hospital,” the receptionist answered.

“Good afternoon, “ I replied. “Can you say if Inshan Ali, the former West Indies Test player, is still a patient there?”

“I wouldn’t be able to say, but I can check with the wards if you can hold?”

“Sure, I will.”

I could hear her euphonious voice, as she enquired at the Nurses Station. I waited patiently, as she diligently checked every ward, to no avail. Further enquiries within the hospital revealed that he had been discharged a few months before.

I turned to Gerry Smith, a Trinidadian friend, who had made the initial queries as to Ali’s whereabouts.

“No longer there,” I informed Gerry.

“Sorry about that, Caura is just about ten minutes away,” Gerry replied.

It was shortly after 3:00 pm on Friday, 9th June, 1995. The sun was high in the clear, bright, blue sky and the heat was almost unbearable. We were standing at a telephone kiosk at St Helena’s Junction, a stone’s throw from Piarco International Airport, where Gerry worked for BWIA (the precursor to Caribbean Airlines).

“Let’s check the directory to see if he is listed,” I suggested, flipping open the two-inch thick Telecommunications Service for Trinidad & Tobago (TSTT) directory securely attached to the booth. Six Inshan Alis were listed.

“Based upon the area code, it could only be this one,” Gerry said, pointing out one of the numbers.

I duly punched the seven-digit code on the keypad.

“Good afternoon, can I speak to Inshan Ali?” I asked

“He doesn’t live here anymore,” a man answered. “I’m his friend Harry. Can I take a message for him?”

“Can you say if he has returned to hospital?”

“Inshan was never in hospital. Who are you looking for?”

It turned out that the Inshan Ali who once resided there was a school teacher. I hung up and withdrew the TSTT phone card. Tracing luck, I had purchased one showcasing the 1994 West Indies team.

I crossed to the cool side of the street where Gerry had retreated in order to escape the blazing sun. What next? Gerry motioned that we head to Preysal, Ali’s home village. After a moment’s hesitation, I agreed. I was only in-transit for 12 hours, and I had hoped to track down Ali in that short window. It was then 3:30 pm and my check-in time at Piarco was 11:00 pm.

A taxi driver advised us that to get to Preysal, “You fellas have to go to Couva, and take a taxi from there.” A short drop in his taxi took us to the Old Southern Main Road at Caroni. There, we joined an old minibus heading for Chaguanas. The journey took us through central Trinidad, sugar cane country. As I gazed out the window at the waves of green shoots of the recently planted crop, I pondered the subject of our pursuit.

Inshan Ali

Inshan Ali was a pint -sized (not that he grew much taller) school boy from the tiny village of Preysal when he first caught the attention of the public. As a back of the left- arm (unorthodox) googly and chinaman bowler, he rose to prominence in the Trinidad and Tobago Wes Hall Youth League. At the age of 16, he made his first-class debut in the Annual North-South match, representing the latter team. His arrival in the national squad soon after, was heralded as that of another mystery spinner from the Hummingbird Isle, in the mould of Sonny Ramadhin, as he was already an exponent of the art of disguising the spin on the ball. In his territorial debut, he snared five for 32 off the Windward Islands.

In 1969, under the outstanding leadership of Bernard Julien, Trinidad and Tobago, the hosts, won the West Indies British American Tobacco (BAT) Under-20 Youth Series. The champions’ team included Ali, already an established member of the senior national side, and the likes of Oscar Durity, Sheldon Gomes, and Richard Gabriel, all of whom would go on to become regular members of the national team, competing for the Shell Shield. This element of youth combined with the experience of veterans Joey Carew, Willie Rodriguez, Wes Hall and the Davis brothers – Bryan and Charlie – led to a revival of fortunes for Trinidad cricket, which had been at a low ebb for some time.

In February/March 1970, a strong Duke of Norfolk XI, led by former England Captain Colin Cowdrey, toured the Caribbean. The squad included then current England Test players, Mike Denness, Robin Hobbs, Phil Sharpe, Derek Underwood and Alan Ward, and future Test players, Jack Birkenshaw, Tony Greig, and Chris Old. The visitors lost to Trinidad by nine wickets, after succumbing to the mesmerizing spin of Ali. In routing the English tourists for 150 in their first innings, Ali captured eight wickets for 58, and then grabbed another four for 95 in the second, as did his fellow 19-year-old teammate, Julien, who took four for 74. It was the Duke of Norfolk XI’s only first-class defeat of the tour. Two weeks later, on the same Queen’s Park Oval wicket, Ali’s three second innings wickets for 21, including the prize scalp of then rising star Lawrence Rowe, contributed to Trinidad’s 219-run defeat of Jamaica, and their first lien on the Shell Shield.

……

The minibus chugged into Chaguanas at 4:30 pm, where the taxi stand was a scene of pure chaos, with passengers, cars and minibuses spewing in all directions. By a stroke of good fortune, amidst the mad scramble of workers clamouring to get home, we managed to wedge our way into a taxi, and were soon flowing on the Southern Main Road. On the way to Couva, as Gerry nodded off, I skimmed my notes.

April, 1st,1971, Kensington Oval, Barbados. Fourth Test, West Indies versus India. With the hosts trailing 0 – 1 in the five-match series, the desperate West Indies Selectors replaced most of the bowling attack, save for Captain Gary Sobers, dropping Grayson Shillingford, Keith Boyce, Jack Noreiga, and Lance Gibbs. The pair of 21-year-old bowlers – Ali, and Uton Dowe, the Jamaican fast bowler – made their Test debuts. There were recalls for the Barbadians, all rounder John Shepherd and medium fast pacer Vanburn Holder, who had participated in Barbados’s defeat of the visitors in the territorial match. Opener Joey Carew, who was injured, was replaced by Maurice Foster. Despite the West Indies compiling 501 for five declared, and then reducing India to 70 for six, the hosts were stalled by a record seventh wicket partnership of 186. On a flat pitch, Ali troubled the lead protagonist, Dilip Sardesai (150), with his chinamen and googlies, but to no avail. Gavaskar (117*), held the second innings together, as the visitors survived for a draw. Ali’s inauspicious debut had yielded a solitary scalp, and the unflattering match figures of 40 overs – five maidens – 125 runs – one wicket.

In 1972, Ali was selected for the Second, Third and Fifth Tests versus the visiting New Zealanders. Confusing the Kiwis with his each-way spin, he always appeared the most dangerous bowler in the West Indies lineup, but suffered from a spate of dropped catches. In the final Test on his home turf, the Queen’s Park Oval, Ali loomed as the match winner, grabbing five for 59, as the tourists were dismissed for 162 in their first innings, 206 in arrears. In the second innings, he snared two early wickets, but the hosts’ push for a series victory, was once again, let down by missed chances.

Sobers, unperturbed, as usual, by the five drawn matches, boldly predicted that Ali would be the trump card against the Australians the next year. It was not to be, as Ali, who would suffer from haphazard selection over the course of his Test career, was chosen for the First Test in Jamaica, and the Third and Fifth Tests in Trinidad. Ali troubled the Australian batsmen, but they were quick to pounce on loose deliveries. Thus, his ten wickets, second to Gibbs’ 26 (at an average of 26.80), were achieved at the hefty cost of 47.30 runs each.

Ali was selected for the First Test of the 1973 Tour of England at the Oval, where the hex of 20 Tests without a victory was finally broken. Ali’s efforts were more noteworthy with the bat than the ball. He scored 15, whilst adding 59 vital runs for the ninth wicket with Boyce, 72, as the West Indies totalled 415 in their first innings. He captured a solitary wicket off 34 overs as the West Indies won by 158 runs. Ali was not selected for the final two Tests, but played in most of the first-class fixtures, where he delivered the most overs (352.2) on the tour, whilst reaping a tally of 38 wickets, surpassed only by Boyce’s 41.

…..

The taxi came to a sharp halt. It was almost five o’clock. It was relatively quiet in Couva, as Gerry and I stood on the pavement – “by that Coca Cola sign and a private taxi will pick you up” – as per instructions from the taxi driver. A private licensed car soon stopped in front of us, “Preysal?”, the driver queried.

“We are looking for Inshan Ali’s home,” Gerry explained, as the car pulled away from the curb.

“I know where he lives, I’ll show you,” the driver and another passenger answered in unison, as if they had rehearsed, as we proceeded east, away from the harsh sun.

We entered the tiny village of Preysal, which had provided a representative on Trinidad teams since the 1960s, and produced two Test players, Ali and Rangy Nanan. We were in cricket country. The game was almost a religion. The name adorning the village’s cricket ground reminds visitors of the favoured son – the Inshan Ali Recreation Ground. The driver stopped midway up a slight slope, in front of a white bungalow. It was 5:25 pm.

A man and a woman were sitting on a bench at the side of the house. We introduced ourselves, explaining our quest. The man, who bore a worried look, was Asgar, Inshan’s father, and the woman was Zolita, one of his sisters, who brought us up to date on Inshan’s status. Her brother, a cigarette smoker, had fallen ill in January, and was being treated for throat cancer. A few weeks prior, he had been transferred to the San Fernando General Hospital. Most weekends, they brought him home to look at his club, Ready Mix Preysal in action.

Asgar, who never missed Inshan’s matches, chipped in that Inshan had made a comeback the previous year, taking 33 wickets in four games. Preysal finished in the penultimate place, eighth, narrowly avoiding relegation from the National Cricket League Division One championship. Wazzard, one of Inshan’s younger brothers, was now a member of the village team. We thanked the Alis for the update and promised to keep in touch.

The sharp sun had taken its toll and I was wilting as we sauntered across the road in search of a ‘private’ taxi. It was 5:50 pm, and the sun was setting as we sipped two Carib beers under the shade of the awning of a roadside bar in Couva. We pondered our next move. San Fernando was an hour away, further south. I opted to call it a day. Gerry persisted that we had come too far to quit. I acquiesced and we boarded a comfortable minibus. Exhausted, I retired to the rear seat, and scribbled a few lines in my notepad.

1974: The Shell Shield Tournament. Ali and his good friend Raphick Jumadeen, a left arm orthodox spinner with a reputation for keeping his end tidy, nearly spun a weakened Trinidad and Tobago team to the title. In the end, they finished runner-up on 26 points, as Barbados, with 30 points secured another lien. Ali befuddled all the batsmen on his way to setting a new tournament record of 27 wickets, taken at the miserly average cost of 16.07 runs per wicket. His list of victims included several of the cream of West Indies batsmen: Roy Fredericks, Rohan Kanhai, Sobers, Viv Richards, Jim Allen, and Lawrence Rowe. In the final match versus Jamaica at the Queen’s Park Oval, Ali had the remarkable match figures of 13 wickets for 98, with second innings returns of 19 – 8 – 20 – 7. The first eight batsmen all fell to the guile of Ali at some stage during the match.

Test series versus England. First Test, 2nd – 7th February, at Queen’s Park Oval. Whilst the West Indies celebrated their first victory in 12 years at the Oval, Ali’s efforts were negligible. A single wicket in the first innings, was followed by a fruitless 37 overs costing 99 runs. Recalled for the Fifth Test at the same venue, his performance with the ball improved, as he took four wickets. However, his batting nearly stole the show, as he waged a fierce battle with the English bowlers. In the final session of the sixth day, the hosts, clinging to their 1 – 0 series lead, were chasing 226 for victory and required 60 runs with only Boyce, Ali and Gibbs remaining. With the home crowd cheering every run lustily and the all rounder Boyce leading the way, Ali fought valiantly for over an hour. It wasn’t to be. England Captain Mike Denness claimed the new ball, and Ali (15) lofted a catch to deep mid-off of Greig (13 for 156). 197 for nine. Gibbs soon followed; the West Indies lost by 26 runs, and England levelled the series.

When the selectors announced the squad for the 1974 /75 Tour of India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, inexplicably Ali was omitted. Trinidadians were very vocal in their protests. It must have been a devastating disappointment to the little man from Preysal, who must have relished the prospect of bowling on the dusty wickets of the Indian subcontinent. The 1975 Shell Shield Tournament brought a modest return of just nine wickets for Ali, as Trinidad finished in the cellar. His performance with the bat was another story. He was the top scorer in both innings in a heavy opening match loss to Barbados. In the second game, at Jarrett Park in Jamaica, Ali arrived at the wicket soon after lunch on the final afternoon, with Trinidad, chasing 351, reeling at 157 for seven. Three and a half hours later, Larry Gomes, 171*, and Ali, 30*, had secured an unlikely draw, having taken the score to 275 for seven.

Ali, in spite of his poor showing in the 1975 Shell Shield, was recalled for the 1975/76 Tour of Australia, but only saw action in the First Test, which the visitors lost by eight wickets. His inclusion was based on his performance just prior, in the state match versus Queensland, at Brisbane, venue of the opening Test. Ali spun the West Indies to victory by an innings and 90 runs in three days, with the superlative returns of: 12.6 – 2 – 42 – 5, & 15.7 – 3 – 36 – 6. Ali did little beyond that on the tour. His swansong Test appearance was in the Fourth Test against Pakistan at the Queen’s Park Oval in 1977, where his five wickets could not compensate for two batting collapses as the home side suffered a humiliating defeat by 266 runs.

Gerry was shaking my shoulder, “Wake up, wake up, we have arrived.” I groggily stumbled from the bus. I rubbed my eyes, 6:45 pm.

The San Fernando General Hospital loomed in the moonlight. Our destination was Ward Eight on the second floor. Cautioned by the guard on the ground floor that it was past visiting hours, we returned to the entrance to procure a special pass, which was kindly provided. All the lights were on in the building. The clean floors glistened as we proceeded to the second level, peering through the windows from the hallway.

“There he is,” Gerry whispered. There was a small television set on a table at the foot of the bed where Ali was curled up, sound asleep; his trademark shock of hair, now grey, still very much there.

We approached the Nurses Station and explained our late intrusion. She replied that she would have to seek Ali’s permission and returned soon after to say that he would be glad to receive us, but we could only spend five minutes.

Ali’s skin was very dark and his visage was that of a very aged person. We introduced ourselves, and there was an immediate sparkle in his eyes. The subject was cricket. He extended his hand. Despite the ravages of his illness, his large palm and unusually long fingers presented a very firm grip. He couldn’t speak, his vocal chords having been removed, but readily grasped the extended notepad to answer my questions.

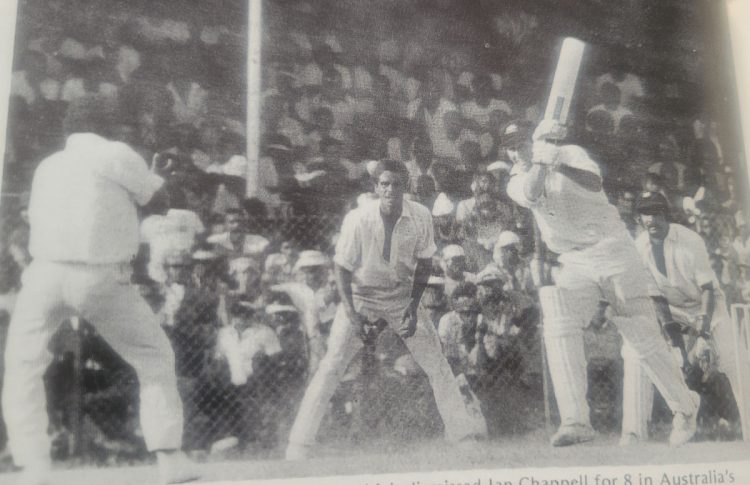

“Most difficult batsman you bowled to?” His quick scribble was very legible: ‘Ian Chappell.’

“The reason for your success in cricket?” ‘I practised everyday from 10 o’clock. It is the only reason why Preysal produces so many good cricketers. Practice. Practice,’ he scrawled again and again for emphasis.

“Best match you ever played in?” Without hesitation, he wrote, ‘1973 Test vs Australia. Oval.’

“Could we have won that match?” The affirmative shake of his head was most definite.

The nurse came in. We had to leave. One final quick question.

“Will we ever see another Inshan Ali?” He smiled broadly and shook his head vigorously from side to side. A rasping sound escaped from the back of his throat, “Noooo, nooo.”

We thanked for his time and wished him well. He smiled warmly as he waved goodbye.

We departed the hospital in silence. It was now 7:10 pm and quite dark. We ambled down the hill, turned right and climbed another hill. We stopped at a roadside bar, where I placed an order, “Two Caribs please.” We sipped the beer in silence, lost in our own thoughts.

We got into a taxi bound for Curepe. The taxi driver deftly wheeled the 280C Datsun cab on to the Sir Solomon Hochoy Highway. Sitting in the middle of the back seat, I watched the speedometer needle in trepidation as the driver accelerated. He soon hit maximum speed, as the ‘clock filled.’ The wind rushed past the open windows, and the voice of Bette Midler wailed from the stereo set.

“From a distance there is harmony,

And it echoes through the land,

It’s the voice of hope,

It’s the voice of peace,

It’s the voice of every man…”

I stared out into the night.

Notes

Inshan Ali passed away on Saturday, 24th June, 1995 at 12:15 am, at the age of 45. It was the third day of the Second Test between England and the West Indies at Lord’s.

Former Trinidad and Tobago Captain Theo Cuffy paid the following tribute, “I have never seen anyone like Inshan, and I will never see anyone like him in my lifetime again. He was a simple man who walked with kings, but never lost the common touch.”

On Saturday, 22nd November, 2014, “Pride of Preysal – The Inshan Ali Story”, written by his sister, Shafeeza Ali-Motilal, was launched at the Couva / Point Lisas Chamber of Commerce in Couva.