The Mayor of New York City, Eric Adams, has been indicted on five criminal counts in a corruption probe involving soliciting bribes from wealthy foreign businesspeople as well as receiving illegal campaign contributions from foreign nationals. The bribes include US$100,000 worth of luxury international travel and at least one from a Turkish government official. Prosecutors alleged that Mr. Adams pressured government officials into approving paperwork for the Turkish House, a Manhattan skyscraper that houses the Turkish Consulate.

The Mayor of New York City, Eric Adams, has been indicted on five criminal counts in a corruption probe involving soliciting bribes from wealthy foreign businesspeople as well as receiving illegal campaign contributions from foreign nationals. The bribes include US$100,000 worth of luxury international travel and at least one from a Turkish government official. Prosecutors alleged that Mr. Adams pressured government officials into approving paperwork for the Turkish House, a Manhattan skyscraper that houses the Turkish Consulate.

Two weeks ago, Jamaica’s Integrity Commission presented a report to Parliament in which it raised serious concerns about the 2021 financial declaration of Prime Minister Andrew Holness. The Commission alleged that Mr. Holness omitted bank accounts from his declaration and had an unexplained increase in his net worth of J$1.9 million, equivalent to US$12,000. The Commission also disclosed that three companies linked to the Prime Minister filed tax returns showing no taxable income, despite conducting transactions worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Additionally, one company wholly owned by Mr. Holness was being investigated for a loan issued to it in the amount of J$50 million, equivalent to US$310,000. The Prime Minister has disputed the Commission’s findings which have been referred to the Financial Investigations Division for further investigation. The Director of Corruption Prosecution has indicated that there is not enough evidence to press charges against Mr. Holness in relation to the filing of incomplete declaration.

According to Transparency International (TI), public officials must be held accountable for accurately reporting their assets, as mandated by law. Requiring asset declarations, along with effective monitoring and enforcement, is key to identifying conflict of interest and fighting corruption. TI further stated that: (i) while the failure to disclose assets does not automatically imply corruption, it is essential that any irregularities should lead to thorough investigations; and (ii) the Executive’s overwhelming control over the legislature in Jamaica weakens Parliament’s oversight ability, creating an environment where abuse and corruption can thrive.

Here in Guyana, the Integrity Commission needs to go beyond monitoring the filing of financial declarations of senior public servants and politicians. With the assistance of experts, it should critically examine all declarations and carry out whatever investigation it considers necessary to ensure they are complete and accurate and there is no mismatch between the declarations and the observable lifestyles of public officials.

In last week’s article, we highlighted the case where the Chinese authorities imposed sanctions against one of the Big Four accounting and auditing firms, PwC, for its failure to detect and report fraudulent transactions involving a failed property developer. According to China’s Ministry of Finance, the auditors were aware of material misstatements in the financial statements of the developer but failed to point them out, and even issued false audit reports. PwC were the auditors of the developer for the past 14 years which raises the important issues relating to audit independence, cozy relationships between auditors and their clients, conflicts of interest, and the provision of non-audit services at the same time.

During the presentation of his 2023 report to the Speaker of the National Assembly on the audit of the public accounts, the Auditor General stated that this was the fourth consecutive year that the report was presented within the statutory deadline of 30 September. While we acknowledge the importance of having timely audit reports, we have always caution against compromising on the comprehensiveness and quality of the audit in order to meeting set deadlines. In today’s article, we explore the topic with specific reference to the auditing of Guyana’s public sector.

The public accounts defined

The public accounts of Guyana do not relate to central government activities alone. By Article 223(1) of the Constitution, they include: (i) all central and local government bodies and entities; (ii) all bodies and entities in which the State has a controlling interest; and (iii) all projects financed by way of loans or grants from a foreign State or organization. We raise this because during its scrutiny of the public accounts over the years, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) has been examining central government activities to the exclusion of those of bodies forming the wider public sector. The latter comprises 180 entities: 39 public enterprises, 61 statutory bodies, 10 municipalities, and 70 Neighbourhood Democratic Councils.

The PAC’s approach serves only to encourage the Audit Office to pay less than the desired attention to non-Central Government activities which are perhaps in greater need for audit scrutiny and reporting. Examples include the Guyana Sugar Corporation, Guyana Power & Light, National Industrial and Commercial Investments Ltd., Mahaica-Mahaicony-Abary Agricultural Development Authority, Guyana Water Inc., and the Georgetown City Council. There are numerous sets of financial statements sitting in the Audit Office waiting to be audited and reported on, especially in relation to local government bodies.

While there is some form of reporting on the accounts of some of the non-central government entities in the Auditor General’s report, it is restricted to audits that have been completed for the period reviewed. In the circumstances, the report does not give a full and complete picture of the status of the results of the audit of all entities forming the wider public sector, which is a significant shortcoming. To ensure the proper and timely accountability for the use of all public resources, which it should be noted belong to the taxpayers of the country, it is highly desirable for financial reporting and audit of all non-central government activities to run in parallel with those of central government. In this regard, legislators have a crucial role to play in ensuring that this so. They must demand from all State-owned/controlled entities in receipt of funds from the Treasury, full accountability in the form of having up-to-date audited financial statements that reflect a “clean bill of health”, as a condition for further funding via the National Budget. The failure to do so would be considered a dereliction of duty to the public.

Deadline for the submission of audited public accounts

Section 74 (2) of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act requires the Auditor General to submit to the Speaker the audited public accounts along with his report thereon within nine months following the end of the fiscal year. This deadline has been in place since Guyana gained Independence when systems and procedures were to a large extent manual. Despite the rapid advances in information technology, this deadline remains in place to date. On several occasions, we have argued for the revision of the accountability timeframe – budget preparation, budget execution, financial reporting, auditing, and PAC scrutiny – so that the entire cycle can be completed within twelve months of the close of the fiscal year.

Apart from ensuring the timely discharge of accountability responsibilities and financial stewardship requirements, the added advantage is that legislators will have an important frame of reference on which to rely when considering the Estimates for the following year. At the moment, the Estimates are approved without any consideration of how the funds allocated in the previous year have been expended.

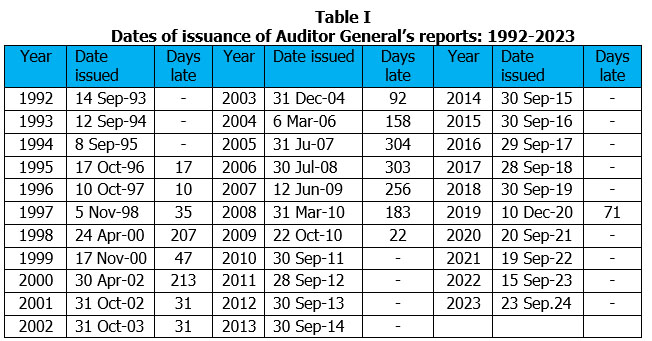

Table I, extracted from the Audit Office’s website, shows the dates when the Auditor General’s reports were issued since the restoration of public accountability in 1992:

It was not until 31 October 2012, some eight years later, that the Auditor General was substantively appointed after he stated publicly that he could continue acting until reaching the age of 65, the then retirement age of the Auditor General. At the time, the Auditor General was about to reach the retirement age of 55 in his substantive position of Deputy Auditor General. When I pointed out that he could not do so and must demit office, the following day he was sworn in as Auditor General!

Prior to 1994, the Audit Office along with three other agencies – Inland Revenue Department, Customs & Excise Department and the Accountant General’s Department – were in receipt of special salaries as part of the Economic Recovery Programme since these offices were deemed pivotal to the country’s economic recovery. However, this special arrangement was discontinued in 1994, as a result of which the Audit Office began to lose qualified staff. This attrition continued until the passing of the Audit Act. This was the major contributory factor for the delay in the finalization of the Auditor General’s report for the years 1995 to 2003.

That apart, the quality and comprehensiveness of the audit could not have been sacrificed for timeliness as there were major issues that had to be dealt with. For example, irregularities were discovered in the Essequibo Road Project involving the supply of inferior quality of stone from overseas, short shipment of stone, diversion of stone to other projects, and falsification of invoices. Another example was the illegal exportation of dolphins. Also, when I returned from Africa after a two-year stint at the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations and assumed duties on 1 September 2004, I found a good deal of unfinished audit work and therefore I could not have closed the 2003 audit in order to meet the deadline of 30 September 2004. It took another three months before I could have done so.

Deadlines for the submission of audited accounts for non-Central Government entities

The respective legislations provide for the audited accounts of public enterprises and statutory bodies to be presented to the National Assembly within six months of the close of the year. It is not clear how many of these 100 entities have complied with this requirement. As regards Local Government bodies, the ten Municipalities and the 70 NDCs are required to prepare and submit to the Auditor General financial statements within four months of the close of the year. The Auditor General audits these statements and issues his reports as soon as practicable thereafter. He is required to give the Treasurer one month’s notice of his intention to conduct the audit, and within 14 days, the Treasurer must publish a notice to this effect. The notice must state that interested persons have the right to inspect the financial statements as well as to make representation to the Auditor General as to the correctness and legality of the accounts, including the entries therein.

Within one month of the completion of the audit or as soon as possible thereafter, the Auditor General is required to submit his report to the municipality or the NDC, with a copy to the Minister. Upon receipt of the report, the Treasurer must publish a notice to this effect, indicating that the report is open to inspection for a period of 28 days.

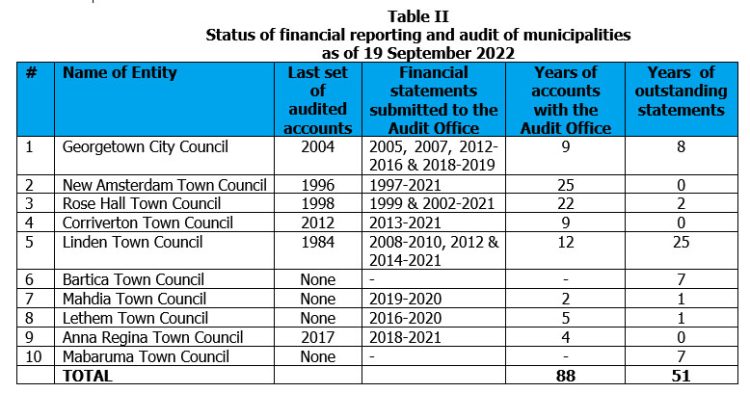

As indicated in our article of 4 September 2023, there were 88 sets of accounts still with the Audit Office in respect of the municipalities, of which 25 relate to the New Amsterdam Town Council, which was last audited to 1996. Similarly, Rose Hall Town Council was last audited to 1998, with 22 sets of financial statements with Audit Office. Table II shows the status of financial reporting and audit of the municipalities as of 19 September 2022:

The above position is unlikely to significantly differ as of last month. We will await the availability of the 2023 Auditor General’s report to confirm whether this is so. It is also unclear how many NDCs have up-to-date financial reporting and audit.