Part 1 – preliminary bookmarks

Transparency under the Public Procurement Act 2003 (the Act or PPA2003) has been of interest in Guyana for some time. Recently two findings on awards already made have been published by the Public Procurement Commission (PPC) which give insight into the modalities of tender evaluation under the Act. A narrative is now proposed over five parts, to shed some light on obstacles to remove or mitigate possible favouritism, waste and fraud in public procurement; and on the potential for overcoming same.

The materials

Whilst some parts of the material could be quoted, most would have to be paraphrased. The narrative will be based on (1) PPA2003 (2) Extracts from a tender report for the Guyana Defence Force (GDF) Reinforced Concrete Wharf at Ruimveldt, as contained in (3) Summary of Findings dated June 24, 2024 published on the PPC website, for a “Bid Protest” for a contract which had already been entered into. Under observation in the narrative are the GDF as the entity expending public funds under a contract with a private-sector, successful contractor in a ‘done deal’; National Procurement and Tender Administration Board, (NPTAB) as agent for the GDF for the evaluation; and the PPC an independent body with certain oversight powers under the Constitution. The first two-named represent the government as important stakeholder; while other stakeholders are the average worker riding home in a minibus, the successful contractor, the bid protestor, and indeed the other unsuccessful bidders.

Even before the ambitious investment plans, decidedly acrimonious political party exchanges have ensued over correctness of public procurement action. Recently in a high-level meeting with senior officials from the Ministry of Public Works and the GDF, amongst others, government warned that any departure from the country’s procurement rules would not be tolerated. Previously government has warned of strict consequences for those found in violation. The PPC in its published findings above, (the Findings) analysed that the protest, in fact by Correia and Correia Ltd, was proper. Despite this to date the PPC has proposed no public resolution to the protestor; fortuitously the Correia and Correia protest is not political party sponsored or supported. (4) More limited reference will also be made to a second published finding regarding an award under the Hinterland Electrification Programme, where a protest was rejected by the PPC without furnishing reasons; this rejection dated December 29, 2023 is also on the website.

100 years ago

Around 1927 a contractor entered into a contract with the local authority in Northampton in the UK, for the erection of dwelling houses. The contractor made an arithmetical error in arriving at his price, having deducted a certain sum twice over. Northampton sealed the contract, assuming that the price arrived at by the contractor was correct. The issue reached the court, which held effectively that the contractor was bound by its original tendered amount, under a principle that the seller of goods (read, contractor) had responsibility of ascertaining the value of the goods which he or she was selling, and bore the risk of the selling price (read, tendered price) being inadequate.

This piece of information is the first bookmarker to be made prior to unpacking what can be learnt from the two PPC publications, and will be referred to below and in a later Part.

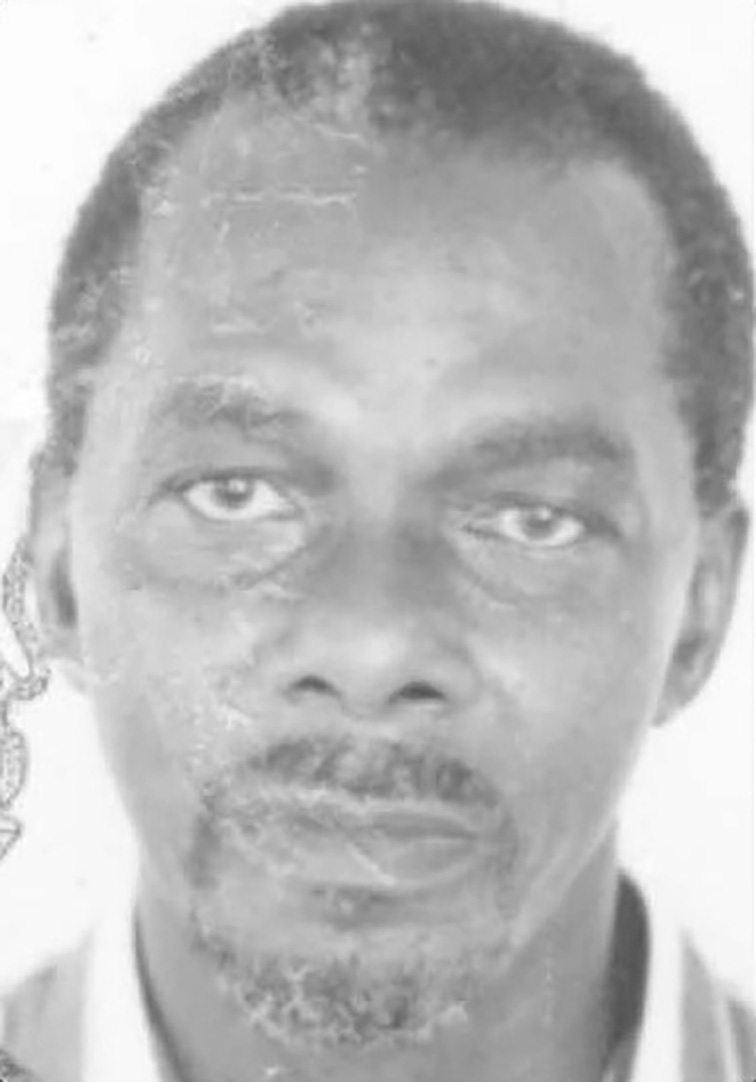

Tribute to Edmund Browne

Few persons would guess that prior to PPA2003 there was a period when fairness in public works tenders was pursued voluntarily. About 1977 when I joined the then Ministry of Works and Housing, the quantity surveying section was headed by Edmund C. Browne who diligently adhered to a ‘Code of Selective Tendering’ when the Section was required to evaluate tenders. The quantity surveying section’s main responsibility was to help drive implementation of the government’s capital programme, contributing an expertise on managing construction costs and timelines. The Code was sponsored by a joint body of professionals and contractors in the UK and set out parameters for both single-stage and two-stage tendering. The latter was used to select a bidder early, during design of the works. This could be intricate, but suffice it to say that at stage one bidders were required to submit piece-rates only, to enable a fair comparison between bidders at stage two.

These procedures were developed, at least in part, by one Aubrey Barker who headed the Section prior to my joining and who had distinguished himself amongst his peers in the Commonwealth, whilst at home the government named a long road after him. Undoubtedly Mr Browne’s management was inspired by his predecessor, but separately there was a dedication in his work, for which tribute ought to be paid now: tenders were examined by tender numbers to avoid or reduce bidder identification; tender amounts must be completed in figures and in words (this avoided misunderstanding as in the Northampton tender, above); and in event of arithmetic errors by a bidder in the bills of quantities, the bidder must stand by the tendered amount or withdraw, (this was really a condition of the Code) all maintained without oversight or even concern by higher authority.

Regrettably the Section was wound up (along with the even more important Architects Section) in the post-assassination 1980’s crackdown on public servants, teachers and others, (including protesting schoolchildren) for reasons never acknowledged by any government since. Emund C. Browne, SLS, Dip Building Economics, (1931 to 2010) the last substantive Head of the Quantity Surveying Section, an unsung professional promoting fairness in public procurement.

New conformity contracts

The Code was discontinued as globally there was an upswing in out-sourcing of government services and public procurement principles were overtaken by mainstream law. This is the third and final bookmark: a principle so overtaken arose in a landmark case in 1990 whereby, if bidders have made a bid-bond deposit required by the procurement entity, as happens in certain

government tenders in Guyana, new contracts are immediately formed between each bidder and the procurement entity whereby the latter is held by strict obligation to give consideration for the award of tender to each of the bidders if, but only if, such bidder conforms to the time and requirements set out in the tender documents; the other side of the coin is that each conforming bidder has an enforceable right (not just an expectation) to be considered for award, along with other conforming bidders. The case hereafter will be called ‘Blackpool and Flyde’; and the new contracts will be called conformity contracts, which are not to be confused with the contract after award, to the selected bidder. Significantly the Blackpool and Flyde principle found its way into the modalities of PPA2003 – as will be seen in later Parts. Hence the award process in question on behalf of GDF comprise three phases: (1) examination of each tender to check for responsiveness to requirements; (2) evaluation of only tenders so conforming, in fair comparison; (3) recommendation to the GDF, who must take responsibility for the award already made.

Enter PPA 2003

The entry of PPA 2003 introduced the principles of fairness and transparency into all stages of public procurement – from first public notice to final de-briefing. This is seen from the statement of intent placed on the forefront of the Act “…to promote fairness and transparency in the procurement process.” with the remainder of the fore page devoted to listing six overarching objectives (the Objectives). As this narrative develops on PPA2003 “promoting fairness and transparency” will the magic words.

The next part will deal with the heart of evaluation.