By Nigel Westmaas

Atkinson Field, situated in what was Hyde Park and later evolved into Timehri and eventually the Cheddi Jagan International Airport, originated as a US military base during World War II. The US presence in British Guiana was bolstered by the 1941 99-year Lend-Lease Act with the United Kingdom, which allowed the US to provide military aid to its allies including the rights to build military facilities in British Guiana. Atkinson Field, like similar US military installations in Trinidad, became a strategic site, contributing to a rise in US military and cultural influence in the region. While ostensibly designed to fight Nazi Germany, Atkinson Field came to represent infrastructure beneficial to both the US and Guyana, resource driven imperialism, and economic and social impacts on Guyanese society.

US Army forces had arrived to survey land for a bomber airfield near Georgetown. Even before it officially entered the war in December 1941, the US had begun construction at Hyde Park, 25 miles south of Georgetown along the east bank of the Demerara River. The site was cleared, hills were levelled, and a long concrete runway was laid. This was in concert with another military base on Guyana soil – a naval air station at Makouria, Essequibo river.

Originally built on a 68-acre tract, with 40 miles of paved roads, Atkinson Field grew into one of Guyana’s most significant aviation facilities. Sources estimate that 6,800 people, including 5,007 Guyanese assisted in constructing both bases “over a 20-month period”. Atkinson Field officially opened on June 20, 1941, with the establishment of a weather station. The airfield was named after Lieutenant Colonel Bert M Atkinson, a World War I aviator who commanded aircraft on the Western Front in 1918. Atkinson retired in 1922 and died in 1937.

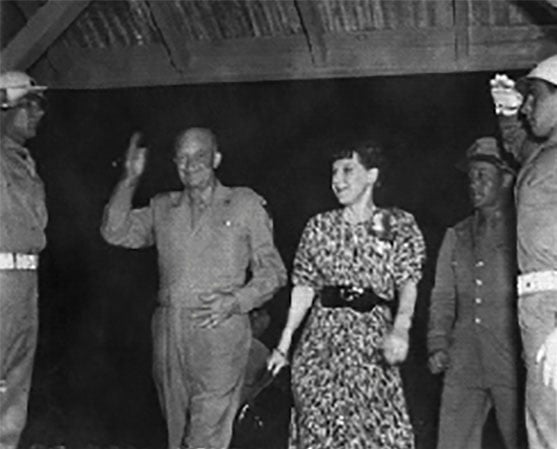

arrive at Atkinson Field airport in 1946

According to the New York Daily News in February 1946, Atkinson Field’s selection was “a natural choice because it is not only the doorway to South America by air but guards the approaches to the Caribbean and that part of South America above the Brazilian hump. It is equidistant 1,500 miles from the Panama Canal and Natal; 2,660 miles from Times Square and only six hours bomber time from Panama and Miami.”

Initially, Atkinson Field’s mission focused on defending British Guiana from German U-boats during the war. It also served as a key staging point for American aircraft crossing the Atlantic en route to the European theatre via the South Atlantic transport route. The airfield played a crucial logistical role, with American aircraft loaded with munitions and supplies ferried across the Atlantic to West Africa and onwards to British forces fighting in North Africa. Around this time, a large American blimp passed along the coast daily, monitoring for German U-boat activity.

Thousands of American troops passed through Atkinson on their way home from the European war theatre under the “Green Project” later described by the US War Department as “one of the greatest airborne troop movements in history”.

High-profile visits to the base, such as those by Eleanor Roosevelt during the war and Dwight Eisenhower in 1946, reflected the growing importance of the Atkinson in the war effort but also its strategic position in the Americas. Five-star General George Marshall also visited the base on at least one occasion. Roosevelt was welcomed by the Governor General at Atkinson not Georgetown, but she had promised to “come again”.

In 1943, with the discovery of bauxite deposits in northeast Brazil, the airfield’s mission expanded to protect the coastline of northeast South America, guarding against potential submarine landings by Axis forces.

Roberta Walker-Kilkenny’s 1990 assessment of US-British Guiana relations during World War II provides a detailed analysis of the strategic importance of British Guiana to the United States. As Kilkenny noted, “From a geopolitical perspective, the establishment of military bases in British Guiana provided a southeastern outpost for US protection of the Panama Canal Zone and was the closest US base to the West African coast and Natal.” But there was more than just strictly military interest. While contemporary US interests in Guyana are centred around its oil reserves, in the 1940s the resources of greatest interest were bauxite, timber, rubber and sugar. Bauxite, in particular, was crucial for armament production.

Atkinson’s infrastructural, social and cultural impact

Ivan Carew, a former Guyanese worker at Atkinson, reflected on his experience with the resident American military and the Guyanese workforce. He wrote that the infrastructure at Atkinson included “power plants, water treatment plants, sewage systems, emergency water reservoirs, a large hospital, barracks, military headquarters, a bakery, laundry, mess halls, aircraft hangars, underground ammunition dumps, canteens and warehouses.” Others mentioned additional amenities available during the war such as tennis courts, basketball courts, a track field, library, gym, and a swimming pool.

Anthony Vieira also highlighted the development of hydroponics (the technique of growing plants using a water-based nutrient solution as against soil) at Atkinson by the Americans: “the hydroponic’s operation I saw at Timehri covered hundreds of square feet in a kind of terrace layout, ie the plants presumably tomatoes, lettuce, bora, cabbage etc were grown in terraces probably hundreds of feet long and 2 ft deep x 2 ft wide, with some sort of cover establishing a greenhouse, to keep out excessive sunlight, insects and rainfall.”

The presence of white American military personnel in British Guiana during World War II inevitably introduced racial tensions. Harvey Neptune, in Caliban and the Yankees (2007), emphasised that the arrival of US military forces in the South American colony of British Guiana “provoked comparable racial anxieties” to those experienced in Trinidad, where the establishment of a US base in 1941 had already led to considerable racial strife.

In Guyana, colonial racial hierarchies were well-established, and according to an unauthorised document at the time: “there is a strong colour line observed in British Guiana… while it does not in any way affect interbusiness relations among the local inhabitants, it is very strongly marked in local contacts.” The leaked missive further noted, albeit incorrectly, that social life in the capital, Georgetown, “may be divided in the following categories: British whites, Portuguese, mixed Portuguese, and mixed coloured.”

The American military was instructed to conform to these racial divisions. Officers were explicitly advised that they were “not expected to associate with groups in this colony with which they would not associate at home,” reinforcing the idea that US Jim Crow racial segregation should be upheld. American officers were expected to follow the example set by British officers and police, who adhered to “fixed social contacts,” ensuring that racial lines were not crossed. Instances of officers fraternising with “undesirable companions,” a euphemism for people of colour, were seen as disgraceful and “reflected discreditably on the command and on the US.”

The enforcement of this colour line was evident in public spaces, such as clubs. Kilkenny noted an incident where “several Englishwomen in the Club protested the presence of Mr Nurse, an Afro-Guianese.” The instructions given to US officers, the adherence to a strict racial hierarchy, and the exclusionary practices in social spaces all serve to underscore the deep entrenchment of race in the daily interactions and power structures in Guyana becoming more apparent in the war years. Yet, in spite of all the “colour line” restrictions, according to Vibert Cambridge in his masterly work Musical Life in Guyana (2015), “by the time the war ended in 1945, there were 79 brothels in Georgetown that catered to American servicemen.” Cambridge also cited information that concluded, “one person in ten in the city (Georgetown) had venereal disease” and wryly declared, “clearly, access to the ‘Yankee bladder’ a euphemism for condoms- was limited to Yankees only.”

Contrasting responses to the base

Kilkenny’s research uncovered two different, but striking responses to the US presence in the colony by Guyanese leaders. In 1944, she noted, President of the British Guiana East Indian Association Jainarine Singh, “met with the US Naval Observer… and Vice-Consul George Widney to discuss US acquisition of Guiana.” However, the article stated that US Secretary of State Cordell Hull, on hearing of the offer, “cabled the Consulate to advise that continued association with Singh and others sharing his views could prove an embarrassment” (to the US).

Contrastingly, Head of the Manpower Citizens Association Ayube Edun had a tiff with the US. In 1945, Edun had called for the return of Atkinson to Guyanese control. In response, he faced astonishing vitriol from the American Vice-Consul, who concluded that Edun was “inevitably anti-American since he was interested in the descendancy of the white race, the ascendancy of the coloured races, and the destruction of the capitalistic system.”

The British Guiana Labour Union, led by Hubert Critchlow, tried to organise bauxite workers in the area but “wartime regulations” disrupted this union activity. Meanwhile, President of the British Guiana Trades Union Council AA Thornr had called on the British government in 1944 to “consider terminating the base agreement at the end of the war.”

Post-war developments

In 1949, another notable event was the suspension of use of the air base at Atkinson Field by the Americans, which was promptly acquired by the government. This acquisition significantly impacted government expenditure, as noted in Hansard on May 17, 1950. However, the airport’s development encountered challenges, and it wasn’t until March 1952 that a new terminal building at Atkinson Field was inaugurated by the Governor while Grumman and Dakota aircraft flew overhead.

Atkinson Field also served as a detention site during the 1953-54 period of political unrest, when members of the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) were held there. This occurred during the so-called “emergency” sparked by anti-communist mania, as colonial authorities feared the growing influence of anti-colonial and leftist forces following the PPP’s victory in the 1953 elections. The colonial government, alarmed by the party’s progressive policies and its potential alignment with global communist movements, declared a state of emergency, suspended the Constitution, and arrested key PPP leaders. According to detainee Eusi Kwayana, when they arrived at the Atkinson detention centre, which was not in direct view of the airport, soldiers were in the process of erecting a barbed wire fence.

On March 16, 1959, Minister of Works and Communication Boysie Ramkarran called Georgetown Mayor Forbes Burnham at the Town Hall from Atkinson via a “new automatic telephone exchange.” Said Ramkarran, “Hello, your Worship, we are calling from Atkinson to inform you in Georgetown that the line is now in operation.” However, in August of the same year, a fire severely damaged the Atkinson airport facility.

In September 1963, the Cuban government requested permission from the British colonial government for its aircraft to refuel at Atkinson Field while en route to other South American countries. Given the Cold War context, it is likely that this request was denied.

By 1965, the US had agreed to review the Atkinson Base pact, signalling a period of reassessment and potential change. Significant investments soon followed with an eye to the continued strategic value of the base in a cold war perspective. On March 17, 1965, the Guiana Graphic reported that the United States provided $2.6 million for a new airport terminal, with plans to replace the old “Atkinson shack”. Later Prime Minister Forbes Burnham declared his intention to review the Atkinson deal. By December 1965, further development was on the horizon, with work on the Atkinson-Mackenzie highway slated to start during ‘freedom month’.

In addition to these political and infrastructural developments, Atkinson Field also hosted car racing events such as “Thrills on Wheels.” Motorcycle and car racing later became a defining feature of the area with the opening of the South Dakota Circuit in 1956, which became a staple for motor racing enthusiasts across generations, continuing up to the present day.

Atkinson Field base was handed back to Guyana with independence in 1966 but as Kilkenny observed, “The Second World war legitimised the US presence in Guiana as security and intelligence force. Both the “Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and FBI were active, together with other intelligence agencies. The Consular officers gathered information as well.” And starkly she noted, “more information on the intricacies of Guyanese economic and political life and terrain were gathered between 1940 and 1946 than during any previous period in the history of US-Guiana relations.”

On May 1st 1969 Guyana’s lone international airport named Timehri was formally opened by Prime Minister Burnham after an expenditure of $7.1 million, including the reconstruction of the control tower and a new runway. Thirty-two years later, in October 2001 Timehri Airport was formally renamed Cheddi Jagan International Airport.

The transformation of Atkinson Field from a US military base to Guyana’s primary international airport symbolised the broader shifts in the nation’s post-colonial trajectory. From its strategic significance during World War II to its role in Cold War geopolitics, the base left an indelible mark on Guyana’s infrastructure, communications, security landscape, and economic development.