Every Man, Woman and Child in Guyana Must Become Oil-Minded – Column 140

Introduction

President Irfaan Ali enjoys his encounters with international journalists, including BBC’s Steve Sackur and more recently New York Times’ International Climate Correspondent, Somini Sengupta. While the President has ably navigated the questions posed to him, he has benefitted from some important questions which Sackur and Sengupta failed to ask – like how he moved from “renegotiation” to “sanctity of contract.” Or the reason(s) for his country’s refusal to join more than 90% of the open countries of the world in signing the global Framework imposing a minimum corporation tax rate of 15% on companies like Exxon, Hess and CNOOC. Whether intended or otherwise, the beneficiaries are the oil companies, the sufferer being Guyana, It now begs the question whether a local journalist would raise these vital topics.

As if the 2016 Agreement is not sweet enough – no taxes, low royalty and a 40-year stability – there is the relinquishment provision which gives Exxon almost exclusive control of the country’s most important sector for decades to come. While Exxon headlines the Stabroek Block, it controls the equivalent of 21% of Guyana’s total area of 83,000 square miles, through its involvement in the Stabroek Block, the Canje Block and the Kaieteur Block. With the exception of the East India Company up to 1857, there are no comparable statistics anywhere in the world, where a company enjoyed such dominant control over any country.

Contract Administration

Having resiled from its renegotiation commitment, the Administration, ignoring the signal failures identified below, boasts about its contract administration, meaning how the Ministry of Natural Resources oversee the operation of the various Petroleum Agreements entered into by the Government of Guyana.

Each and every failure comes at a cost and while the focus has understandably been about the Stabroek Block, it has detracted from Exxon’s role in two other blocks – the Kaieteur Block and the Canje Block, with significantly smaller areas than Stabroek.

Contract administration is a critical aspect of resource management, where the State must ensure that contractors fully meet their legal, fiscal, environmental and other obligations under their Agreements. Equally important is avoiding situations where, through poor oversight, negligence, or incompetence, companies receive greater benefits and more latitude than are legally permissible. Unfortunately, from the very inception of the 2016 Agreement, there have been concerning lapses in administration.

Contract failures and relinquishment

Raphael Trotman allowed Exxon to claim US$460 million in pre-contract costs, significantly more than their own financial statements revealed. Eight years after the Agreement was signed, not a single Ministerial audit has been completed, with only two audits combining several years instead of the required seven annual audits. Then there is the case of a staggering sum of US$211 million of unsupported expenditure being cleared at an administrative level rather than by the Minister of Natural Resources.

These issues are facilitated by inadequate accounting and reporting, weak and permissive environmental oversight, and a lack of disclosure and accountability.

Another critical failure is in the handling of relinquishment provisions under the various Petroleum Agreements. “Relinquishment” refers to the obligation of oil companies to give up, within no more than ten years, the area over which they are granted a prospecting licence. This provision is crucial for ensuring that areas not explored, or which are proven unproductive are returned to the State, allowing for potential reassignment or conservation.

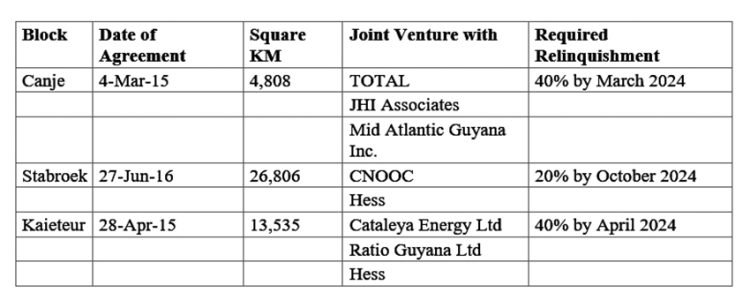

To understand the scale of this issue, let us examine the three Blocks where Esso is the Operator. According to the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission, these Blocks are as follows:

First, two quick asides. Exxon was permitted extraordinary latitude under the relinquishment clause of the 1999 Agreement, and now, under the legally questionable 2016 Agreement, it is allowed seven years instead of the usual four before it relinquishes any of the vast blocks it was awarded. Utilising an exception permitted in the then law, all that is required of Exxon after four years is to request a renewal, without any obligation to relinquish.

At the end of this renewal period, which lasts for three years, Exxon must request a further three-year renewal but must relinquish at least 20% of the original Contract Area, excluding Discovery and Production Areas.

The retained area should comprise no more than two discrete areas, no piece by piece. At the end of that second renewal period, i.e., after 10 years, Exxon shall relinquish the entire Contract Area, with the exception of Production and Discovery Areas and Areas under Appraisal Programmes. The Agreement was signed, dated and executed on 27th June 2016 but notarised on 7/10/2016 – which can be interpreted as 7th October 2016, or 10th July 2016. Even if we accept the word of Exxon’s former clandestine public official doing secret PR work for the company, Exxon should have given up 20% of the Stabroek Block no later than 7th October of this month. The big question is whether any such relinquishment has been effected. For the Canje Block, 20% of the contract area should have been handed back by 4th March 2019, and another 20% by 4th March 2022, with the remainder to be handed back by March 2025. For the Kaieteur Block, 20% of the contract area should have been handed back by 28th April 2019 and another 20% by April 2022, with the remainder to be handed back by April 2025.

Question of Administration

All companies awarded petroleum agreements must apply for renewal of their licenses before the current period ends.

This is crucial because each renewal comes with the obligation to give back (relinquish) part of the area they control. In this regard, I do not recall any public disclosure of timely applications for renewals, the extent of the relinquishments and whether the applications were granted.

The administration of the petroleum agreements covering vast areas of Guyana’s territory is about the country’s sovereignty as well as our national patrimony. The public has a right to know how these areas are being managed. Any carelessness in administration comes at a huge cost to Guyana, and by not enforcing relinquishments as stipulated, the country can lose opportunities to re-auction areas bringing in substantial revenues since the country is de-risked.

Conclusion

The administration of Guyana’s oil blocks reveals a complex picture of rapid development coupled with significant challenges. While the success of the Stabroek Block has brought benefits, the apparent lack of enforcement of relinquishment provisions in other blocks raises serious concerns about the overall management of our oil resources.

Next week, we will look at the Prime Minister Samuel Hind’s defence of Exxon.