By Nigel Westmaas

The contribution of early radical movements and individuals in British Guiana (Guyana) to the anti-colonial, labour, and nationalist movements is an underexplored but pivotal aspect of the country’s history. The radical tradition in Guyana spans centuries, from the early enslaved rebellions and maroon resistance to the emergence of organised labour, indentured labour insurgency, and nationalist struggles. Radical movement theory suggests that such movements are born out of profound dissatisfaction with entrenched systems of power and reflect an intersectional resistance to multiple, overlapping forms of domination, including economic exploitation, racial subjugation, and political disenfranchisement. Whether expressed through rebellion, strikes, or political organisation, early radicalism was driven by an inherent resistance to these systems and the desire to transform the socio-political landscape.

However, this radical tradition was far from monolithic. It encompassed a spectrum of ideologies and motivations, ranging from the outright revolutionary ambitions of the 1763 revolution to the more reformist goals of early labour unions and the Marxist aspirations from the 1940s. The colonial radical tradition in British Guiana was not solely defined by direct confrontations or insurrections; it also involved creating new spaces for agency, expression, and alternative political visions, often in defiance of powerful colonial forces. This summary traces the role of these radical movements and individuals in influencing change in the colony, spanning from emancipation in 1838 to independence in 1966.

However, this radical tradition was far from monolithic. It encompassed a spectrum of ideologies and motivations, ranging from the outright revolutionary ambitions of the 1763 revolution to the more reformist goals of early labour unions and the Marxist aspirations from the 1940s. The colonial radical tradition in British Guiana was not solely defined by direct confrontations or insurrections; it also involved creating new spaces for agency, expression, and alternative political visions, often in defiance of powerful colonial forces. This summary traces the role of these radical movements and individuals in influencing change in the colony, spanning from emancipation in 1838 to independence in 1966.

Post-emancipation origins

The first known public reference to ‘socialism’ in Guyana dates back to 1839, when an article in the London Times described the fledgling post-emancipation village movement as “little bands of socialists.” Though intended as criticism, the remark, given the context of the time, was a backhanded compliment, acknowledging the vision and resourcefulness of these early Guyanese villagers, who pooled their savings to purchase and lease former plantations collectively.

Throughout the 19th century, other individuals—Black, Brown, and White, both European and Guyanese—were labelled ‘socialists’ by the colonial state and press for their radical views. Walter Rodney has chronicled the activism of Reverend H J Shirley, who arrived from England in 1900 to serve at the New Amsterdam Mission Church. The colonial press responded with hostility to his work. After declaring, among other things, that British colonial authorities intended to keep “the Black and coolie people in ignorance” and calling for the formation of trade unions, Rev Shirley was branded a “socialist demagogue.” His bold stance led to his surveillance by the Special Branch following the speech where he issued his call.

In addition to Rev Shirley, there was Bechu, an Indian immigrant and firebrand who caught the attention of the colonial authorities. Prominent Guyanese historian Clem Seecharan has chronicled Bechu’s efforts in the colonial press, describing him as an “extraordinary indentured labourer—a rebel shaped by the radical intellectual temperament of late 19th-century Bengal.”

This description highlights Bechu’s impactful and combative letter-writing to the colonial press between 1894 and 1901, which underscored his defiance and intellectual rigour.

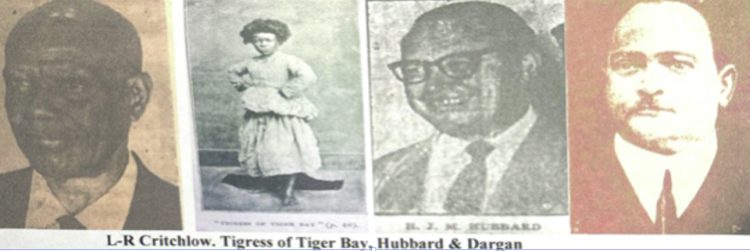

Women were by no means excluded from among these early firebrands. From their visible and leading presence in the 1889 and 1905 riots all manner of titles were placed on them by the colonial press. The many unemployed women who participated in these and other demonstrations were deemed “amazons”, “idle ruffians” and “women of the street”. In some cases they were more feared and loathed than the ‘socialists’ in the colony. The 1905 riots popularised by Rodney was an impactful rebellion of the working people in Guyana. Hubert Critchlow, a dock worker at the time, was present in the disturbances and his “witness” of the events reportedly prompted him on a trade union career. Patrick Dargan, another radical firebrand, became an even more prominent and almost indispensable voice in the struggle against police officials, the economics of the colonial state; as well as an active user of the colonial and ethnic press.

Post War I radicals

The second broad phase of leftist, anti-colonial, and nationalist rebellion could be said to have commenced with the onset of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Coincidentally, but concurrently, trade unionist Hubert Critchlow (along with others) viewed the revolt as a victory for the working class. Not long afterward, in 1919, he co-founded the British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU). The BGLU, however, was much more locally derived and inspired, focusing on the numerous issues affecting the Guyanese working class inclusive of living wage, rent control, taxation, sanitation, labour abuses, and social welfare services.

Communism, as it emerged following the Russian Revolution, quickly permeated discussions in the colony, even as the BGLU was being established. The Daily Chronicle of April 23, 1919, sounded a typical alarm, playing on the fears of the influenza epidemic then sweeping the colony. It ran a headline warning of the “Spread of Bolshevism: France Infected”.

The 1919 seditious publications ordinance in Guyana was part of the broader “red scare” of the period and aimed at radicals of any stripe. Among other active groupings in the colony in the period was Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). While Garvey’s UNIA was ideologically multifaceted, Garvey admired Lenin, and in 1920 he wrote, “why should we not seek an alliance with Trotzky and Lenine [sic].” Other groups in the colony included the communist leaning, internationally based African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) led by Cyril Briggs of Nevis.

In the 1920s, A R F Webber and Nelson Cannon founded the Popular Party, a moderate, middle-class movement that nonetheless drew intense opposition from the plantation elite, the governor, and pro-establishment newspapers. The backlash included satirical cartoons branding Webber and his associates as “communists.” Webber emerged as a staunch critic of the colonial state, vehemently opposing the Crown Colony plans and their implementation in 1928. In what one author described as Webber’s own “Massa Day Done” speech—delivered 25 years before Eric Williams’s famous declaration—Webber declared, “The men who are hailing Crown Colony government with the elimination of the control of the popularly elected representatives, are lineal descendants of the men who soaked this colony and many others in blood, in the vain attempt to bolster up slavery.”

Guyanese activist Gertie Wood was a prolific advocate for women’s empowerment in the 1930s, urging them to “throw off the shackles of slavery, prepare yourselves to fight your own battles and read every book and paper you can get hold of, ask questions about all sorts of things…” Another figure whose brief yet impactful career in resistance was largely omitted from formal history is the self-styled Rev Claude Smith of the ‘Church Army of America.’ Although the local newspapers were skeptical of Smith and dismissed him as ‘a demagogue,’ he appeared deeply committed to aiding the poor. He led an ‘army of the unemployed’ in opposition to colonial conditions, making representations on behalf of the people—primarily in Georgetown.

Critchlow’s socialism

By the 1930s, Critchlow’s political statements had become more distinct. After calling for “universal manhood suffrage” (in 1929) he proceeded on a trip to London in 1932. After London, he visited Germany and Soviet Russia. On his return to British Guiana, he is reported to be the first individual to introduce the term “comrade” to the colony and began to uphold the Red symbols in May Day marches. An editorial in the Daily Chronicle in 1932 was critical of his connections with the moderate international trade union organisation, the ICFTU, and his alleged familiarity with socialism. The editorial suggested, “Critchlow was one of the few persons in the colony that understands socialism, but his knowledge is so profound that much of what he says passes over our heads.” It was certainly Critchlow’s intent to aim for those heads when, in one of his speeches in the 1930s he called for the organisation for workers to “achieve the overthrow of the capitalist class.” In March 1932, Hubert Critchlow, then General–Secretary of the British Guiana Labour Union, went up to Fyrish Village on the Corentyne to deliver a speech at the Congregational Church on the theme of “Jesus and Labour”. In arguing that Christ was a true socialist, Critchlow appeared to gently chide the church establishment for moving away from the “socialistic” actions in the life and work of Jesus Christ. Likewise in 1933, Hubert Critchlow sent a letter to the ‘Secretariat International Red Aid’ in Moscow, USSR, which was published in the Negro Worker. Signing the letter as “Comrade,” Critchlow outlined the actions he took upon returning from his visit to the Soviet Union.

HJM Hubbard and the PAC

A further phase in the development of the radical movement can be traced to the impact of the Second World War and its aftermath. In the 1940s a pioneer trade unionist, Jocelyn Hubbard, and a few of his friends, presumably the first group of formal Marxists in the colony, established what has traditionally been called the Marxist circle. The victories of the Red Army over Hitler appeared to have stimulated (essentially middle class) individuals like Hubbard, bringing into question the “pre-war propaganda of an inefficient and hungry Russian nation…” In his work, Race and Guyana Hubbard also referenced the birth of the Victor Gollancz Left Book Club, named after a prominent European Marxist. Ashton Chase credits Hubbard with becoming a Marxist when it was unfashionable and also dangerous: ‘he had a background of studying Marxism on his own’. Webber’s group held regular classes and studied the works of Karl Marx, Lenin and other communists and socialists. Furthermore, left publications had begun to penetrate Guyana by this time. Some of these works included Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China, and John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World.

The formation of the Political Affairs Committee (PAC) in 1946 marked a pivotal milestone in Guyana’s Marxist movement. It is now well established that with the coalition of Cheddi Jagan, Jocelyn Hubbard, Ashton Chase, and Janet Jagan, the PAC emerged as the first explicitly Marxist political group in the colony. Among the original goals of the PAC was the aim to “assist in the growth and development of labour and progressive movements of British Guiana to the end of establishing a strong, disciplined and enlightened party, equipped with the theory of scientific socialism…” The PAC grew rapidly, significantly bolstered by Cheddi Jagan’s militant advocacy both inside and outside the halls of power beginning in 1947. The PAC attracted several notable individuals, including a young lawyer, Forbes Burnham, who returned in 1949 with reputed ties to the British Communist Party, as well as fellow traveller figures such as Rory Westmaas, Martin Carter, and George Bowman.

PPP rise

In 1950, a coalition of individuals and organisations came together to form the People’s Progressive Party (PPP). One of the defining characteristics of the early PPP was its diverse, multi-racial support base, which included small shopkeepers, government workers, middle-class professionals, small farmers, sugar workers, and the unemployed.

Within this coalition, a Marxist core that aligned with the principles of Marxism-Leninism was clearly discernible. However, at the grassroots level, there was “no serious drive … ever made to inculcate Marxism in them.” The rhetoric from PPP leaders, along with frequent references to leftist causes and Marxist theory, led many to mistakenly believe that the early PPP was a ‘Marxist-Leninist’ party modelled after Communist organisations in Europe and Latin America. In reality, the PPP’s ambitions in the early 1950s were far more restrained. As Eusi Kwayana reflected, “I don’t think anyone in the party thought they would introduce socialism… we had discussed it, but I don’t think anyone among the leadership had any such ideas.”

In the general elections of 1953, the PPP prevailed. Given it was a strident left-wing organisation working in a hostile colonial administration and in a hemispheric climate of anti-communism, its impact and success at the polls was remarkable. But the very ‘success’ highlighted latent weaknesses in the movement. In giving history a ‘shove’ in 1953 the PPP appeared to harness multiple processes: the popularity of some of its individual leaders; the anti-colonial sentiments; and strong labour roots.

Before independence, Guyana was divided between political parties along racial lines, leading to significant disunity. Although the left-wing impulse was primarily maintained by the PPP, it was also present within the People’s National Congress (PNC), despite the PNC’s growing alignment with American hemispheric interests. The youth arms of both parties, the Young Socialist Movement (YSM) and the Progressive Youth Organisation (PYO), actively engaged in issues abroad aligned with anti-colonial and socialist ideologies. In March and April 1965, they invited each other to rallies promoting national unity, peace, and socialism. Prior to this, in 1960, Brindley Benn, a former Deputy Premier for the PPP, made the now-famous declaration: “It’s easier to stop tomorrow than to stop communism”.

In summary, Guyana’s reputation for radicalism in the social, political, and international spheres was shaped by a diverse array of individuals and organisations who, over time, helped to frame the modern Guyanese political consciousness. This evolution, however, would likely not have been possible without the multi-dimensional legacy of radical struggle forged by the collective contributions of early firebrands, trade unionists, and movements.

(NB: This article is a condensed and revised version of a book chapter by the author, featured in The Red and Black: The Russian Revolution and the Black Atlantic (Manchester University Press, 2021)