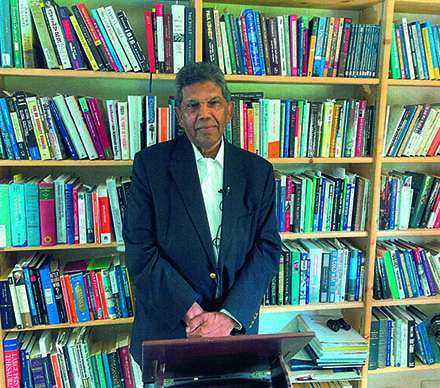

Ta-Nehisi Coates is one of America’s foremost writers, now a Professor at Howard University. His parents named him Ta-Nehisi to give him an identity with a great African civilization.

He has been in a life-long quest for justice for his Afro-American compatriots, and his message has spread to the world. He is a champion of reparations for slavery. He is a champion of the dignity and worth of every human being. He highlights situations of injustice.

He has recently visited Senegal and Goree Island, a former slave depot, to take in the vibrations of his ancestors on the African continent – and to connect it with his experience as someone born and raised in an America still laced with racism. And he has visited Israel and Palestine and written about what he saw with deep feeling – and with a passion for justice.

In way, Ta-Nehisi has a literary connection with Guyana. His father developed himself, gave himself an education through reading. He was passionate about reading. And one of the books he had read was about a slave rebellion in eighteenth century British Guiana. His father “loved the book but was pained by how the rebellion concluded – not just in defeat but with its leaders turning on each other and ultimately collaborating with the very people who had enslaved them.” The name of the book is not given.

Ta-Nehisi’s parents encouraged him to read: Read, read journals, read newspapers, read books. And now Ta-Nehisi writes books. Highly acclaimed books. He has won prestigious prizes for his writings. And in 2024 he has published his latest work, ‘Message’. It is a message of Justice: a call for justice; and the exposure of injustices.

Reading the book is to go into the mind of a person who is poignantly asking: why were my people, Africans, considered inferior to white people. Who could invent such a monstrosity? And why is this allegation of inferiority still pervasive in twenty-first century America? How can we explain the barbarities to which our African ancestors were subjected? How are we to do justice to our ancestors? How are we to secure justice for ourselves? Ta-Nehisi is looking for answers.

His writings have been put on lists of banned books in some southern States of the USA whose State governments have legislated that ‘critical race theory’ is not to be taught in schools, and books about them are not to be in libraries. This is an active battle of ideas, of ideologies, being waged in contemporary America.

The prevailing racial situation in America is one of the four theatres ventilated in Ta Nehisi’s ‘Messge’. A notable feature of the book is that it provides a window into the mind of an Afro-American who is calling America to conscience. He is asking: “Why, Why, Lord, are we still so unjustly treated. How can this be?”

The message here for Guyana is that we must listen to the hearts of all our people, with their historical and contemporary experiences, and our leaders must constantly strive to understand, and to respond with a matching quest for justice in their hearts. Vision, content, tone, and message are crucial here. As is wise leadership.

The second theatre of Ta-Nehisi’s ‘Message’ is his own mind. He is an American of African ancestry, born and raised in the USA. He wants to discover himself. He draws upon his experiences of growing up, and living in America. And he wants to personify the dignity and history of his African ancestry.

He has experienced the Atlantic from its American shores and he has feelings about that. Now he must experience it from its African shores – to see what he feels from that vantage point.

To do this, he makes his first visit to Africa, to Senegal, and to the notorious former slave depot on Goree Island. He visits Goree Island, and the wind and the waves of the Atlantic, lapping on the African shores, speak to him. But he is not sure what they are saying. He will have to process that as he goes along.

He enters his third theatre as he interacts with Senegalese friends and associates in Dakar, Senegal. What does he feel? He is an African-American; they are African-born and raised. Who are they? And who is he? He has to process this also. One of the people he meets at a discussion group is a young female Senegalese student doing a doctorate degree on the writings of Ta -Nehisi Coates.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is seeking to learn about Africa; and they are seeking to learn about him! About Afro-Americans. This quest for mutual understanding is an ongoing story and one suspects that Ta-Nehisi will write further about this in his future renditions. And he will write about it with elegance and passion.

As he has written about the fourth theatre in his book, his visit to Israel and Palestine. He goes there as a participant in a meeting of writers. He visits the Yad Vashem museum in Israel dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Holocaust. And he is moved by what he sees: A Book of Names, with the names of six million Jews who had perished in the Holocaust inscribed, recorded for history. And he is moved by this injustice. He feels for it.

As he feels for the Palestinians. The Palestinians inside Israel who need permission to move to, and live in, certain areas. The Palestinians of Gaza and the West Bank who have been under occupation since 1967 – a long, long occupation. And his heart is moved.

And his heart is broken as he sees the plight of the Palestinians in Gaza. His heart is also shredded as he sees, in the West Bank, that settlers have well-built roads for themselves, while Palestinians must navigate rudimentary pathways, the pathways of their suffering. License plates of cars have different colours for settlers and for Palestinians. The license plates determine which roads each group can use.

He sees ‘settlements’ that are well-built neighbourhoods, some with swimming pools. And he sees Palestinians making do with the housing they have inherited. It is against the law for Palestinians in the West Bank to have receptacles for collecting rain-water. The Administering Power has ordained that rain water must be allowed to fall to the ground so that they can collect in aquifers and be available to the Administering Power.

And Ta-Nehisi sees many more things. He writes passionately about what he has seen, and he has run into criticism for this – criticism that he has rejected. The reader will have to judge for herself, for himself, where justice lies. Ta -Nehisi is inviting the reader, is inviting the world, to be attentive to the need for justice. To be passionate about justice, as he is.

And that is another poignant message for Guyana: to be always in a quest for justice for everyone, for all groups. And to be seen to be in the quest for justice.

Ta-Nehisi records the message of his father after he had read the book about the slave-rebellion in British Guiana: “He loved the book but was pained by how the rebellion concluded … He sighed as he recounted it to me and said, ‘I don’t think we are going to get back to Africa’. My father did not mean this physically. He meant the Africa of our imagination, that glorious Eden we conjured up as exiles, a place without the Mayflower, Founding Fathers, conquistadores, and the assorted corruptions they had imposed on us. That Africa could no longer even be supported in his imagination because the corruption was not imposed at all but was in us, was part of the very humanity that had been denied to us. That is where his sceptical searching landed him – not on the shores of a lost utopia but in the cold fact of human fallacy. And yet here I was, on this boat from Goree, my eyes welling up, grieving for something, in the grips of some feeling I am still, even as I write this, struggling to name.”

Ta-Nehisi is beckoning everyone to reflection, to Justice. Every citizen of the world; Every Guyanese. He is saying: Humanity matters; Vision matters; Message matters; Leadership matters; Justice is the lode-star.