Having provided 26 years of voluntary service in sport administration nationally, Dr Karen Pilgrim, a veterinarian by training, believes that Guyana will not achieve the glory it is seeking in the field of athletics until it institutes proper programmes in schools, and sport no longer has to depend heavily on volunteerism.

“That is just my Jamaican bias talking. Without proper sport programmes in schools, we will not be able to capture the talent,” Pilgrim, who spent most of her childhood in Kingston, Jamaica, told Stabroek Weekend in an interview.

“Once sport depends on volunteers, there will always be a limit as to how far we can go because volunteers take time off from jobs etc. I was lucky that after leaving the Ministry of Agriculture in 1998, I worked according to my time,” she said.

Pilgrim’s entry to sport administration began when she was voted into office at a swim club without her knowledge. Her son, Damian, first took swim classes at the Ambassador’s Club while in primary school. When he started high school, he wanted to swim, and Pilgrim sent him along with a friend from Tucville, whose son wanted to learn to swim, to Castellani Swimming Pool.

She thought it would be like what she did in Jamaica, where she went to the YMCAto swim three days a week and that was it.

One Sunday she was asked to attend a club meeting for elections for office bearers.

“I had no idea what they were talking about. How could they have elections when you’re just paying someone to teach you to swim?” she related.

That Sunday being Father’s Day, she decided not to go. That evening, she got a call congratulating her on being elected secretary of Dorado Speed Swim Club.

“I was suddenly the secretary of a club I never knew existed,” she said, adding that she remembered one of the things her mother often said, ‘Anything that is worth doing, is worth doing well,’ and so she said, sure, why not?

Shortly after, she became Dorado’s representative at the Guyana Amateur Swimming Association (GASA) then was elected secretary of GASA.

“I believe that if you are doing something you must immerse yourself in what you are doing. I attended all of FINA [International Swimming Federation and now World Aquatics] coaching clinics just to understand the strokes and to learn about swimming even though I have no ambitions of being a swim coach,” she said.

She became GASA’s representative on the Guyana Olympics Committee (GOC) and subsequently served as GOC vice president for eight years; she also served GASA for eight years.

Through the GOC, she accompanied several local teams as chef de mission to Youth Olympics and Commonwealth games, the 2012 London Olympics and the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham, England. She has travelled with teams throughout the Caribbean and South America, with the most recent being to French Guiana for the Inter-Guiana Games (IGG).

She has attended the IGG through the National Sports Commission as a member of the IGG management team since 2009.

Anti-doping

In 2009, the GOC was invited to nominate two people to be trained in Barbados as antidoping officers; Pilgrim was one of the two nominated. The training was a simple, but detailed and precise process, she said.

“It is a significant exercise because it places the careers of athletes in our hands. Little by little that role has expanded where there is need for a structure to be established in Guyana and the Caribbean. The overall work of doping control has evolved into much more because the World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) has increased responsibilities,” she said.

From collecting and testing samples antidoping officers are now required to conduct educational awareness on doping control, even on demand.

WADA has also added more requirements to what needs to be done in terms of compliance, she noted

At present, Pilgrim is one of three people from the Caribbean taking part in an antidoping media relations and communication programme involving 17 people from around the world.

One of the things explained is that before the communications department sends out a press release, antidoping officers need to consult with their legal department.

“Imagine, the three of us sending messages to each other saying, we need to talk to ourselves because we do not have anti-doping agencies in the region. Some places like Australia talk about gelling with their legal team and having only three or four people in their commu-nications department. We have nothing of the sort in the Caribbean,” she noted.

Antidoping could easily be a full-time job in sport here in Guyana, she said, adding, “The Guyana Olympics Asso-ciation is, by default, an antidoping entity and until we have a separate autonomous anti doping organisation, that is my link to GOA,” she said,

At the club level, Pilgrim is still involved in swimming.

Sport awards

For sterling contribution to the development of sports in Guyana, Pilgrim was awarded the Golden Arrow of Achievement in 2016. She has also received several awards from the National Sports Commission for her contributions.

The first award she remembered receiving was for wildlife conservation from the Audubon Society.

“They also presented me with US$1,000, which was like a hundred million dollars for me at the time,” she recalled.

Asked about treatment from her male counterparts in a sport-dominated world, Pilgrim said, “I get automatic respect even if it is just lip service because people meet me as Dr Pilgrim. However, I have seen other women, much more deserving of respect than me for what they have done for sport and what they have accomplished while facing other challenges, being disrespected. It is horrendous.”

At the associations’ level in general, she said, improvements are seen at certain times but that is based on who is holding office.

“I can’t say I have seen steady progress in any association as a model of governance and fundraising. However, since I have been in sports, I have seen vast improvements at certain levels among individuals. Athletics for sure and swimming to an extent. Squash player Nicolette Fernandes, who has always had us on the map and other squash players. I have seen some youngsters in cycling who have passed through my hands and who have gone on to do fantastic things,” she said.

“In swimming are Raekwon Noel, Aleka Persaud and Leon Seaton. If you ask who is behind them, I cannot readily say it’s an association. The people I know who went onto the Olympics from Jamaica weren’t even in clubs. They were doing sports in schools. Jamaican Olympian Grace Jackson wasn’t in a club. Even if her parents could have afforded the club fees, they didn’t think women should be in sports.”

Jackson won a silver medal in the 1988 Seoul Olympics and was a former Jamaican record holder in the 200m and 400m races.

Sharing a verse of good wishes from one of her many adopted children she obtained through sport, Pilgrim said, “The best part of being in sport is meeting a lot of young people. They sometimes seek advice, or they just need to hear something from somebody. Athletes staying in touch with me is a joy.”

Background

Pilgrim spent her early childhood in Kitty when it was a village and what is now Clive Lloyd Drive – from Kitty Pump Station to the Russian Embassy – was a dirt road.

“From my grandmother’s house we jumped the fence to get to the seawall. A lot of land was on the other side of the seawall which has since eroded substantially. We played hide-and-seek, caught crabs and did other fun games,” she related,

Former foreign affairs minister Rashleigh Jackson who lived in the bottom flat of her grandmother’s house, and Leila Loncke who lived in another part of the house, were uncle and aunt to her at the time. As an only child she accepted their children as her siblings.

“I grew up with two of my uncles, Nicky and Jimmy Harewood, who were close to my age anyway,” she recalled. “My grandmother lived at 41 Public Road, Kitty and we were at Lot 69. I walked to my grandmother’s place every afternoon to play, climb trees and, according to my mother, make a mess of the dresses she so carefully made for me. I never liked dresses.”

In 1969, just before her ninth birthday, her family moved to Jamaica because of her father, Cecil Pilgrim’s diplomatic posting. She attended the Queen’s School where she wrote common entrance in Queen’s Preparatory and completed her junior and senior secondary education in Queen’s High School in 1978.

On leaving school she applied and successfully gained a Guyana Government scholarship to study veterinary medicine at Tuskegee University, Alabama. To be eligible, she returned home to complete a three-month stint in the Guyana National Service. At that time her orientation was Jamaican.

“I think it was more useful for me than the other candidates. I was just happy to meet locals. Even though I came home on holidays from Jamaica, I didn’t know many people. We camped in for a short period in Sophia but most times we went in the mornings and returned home in the afternoons. Sophia was not like it is now. I felt like I was going out of town,” she said.

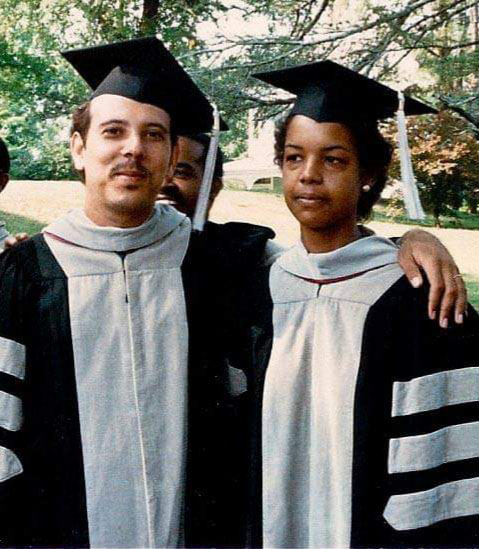

Pilgrim spent seven years (1978-1985) at Tuskegee University where she obtained a bachelor’s degree in animal and poultry science and a doctorate in veterinary medicine.

Returning home she was more a foreigner in her country of birth. When she enquired about the possibility of accommodation, she was told she could get a flat at Main and New Market streets. She remembered Main Street because she attended Stella Maris and Sacred Heart Primary schools before going to Jamaica.

“New Market Street, I hadn’t a clue. I remember the National Library because that was where my grandmother [Margarita Harewood] worked, hence the supply of books that I didn’t even need to leave the house when I came home on holidays. Finding places was embarrassing for me. I was lost on the names of streets and villages,” she said

Her reorientation along with two other vets who were trained in Cuba consisted of one month of familiarisation at the head office in Regent Street and Vlissengen Road, a month each at the veterinary laboratory, and at the livestock farm at Mon Repos, East Bank Demerara.

“That introduced me to Georgetown and the environs… I think I adjusted quickly,” she added.

Single regret

During her first month of orientation, Pilgrim was instructed to go to Rupununi on a Guyana Airways Corporation flight to collect the brain of a horse suspected to have had rabies, take in some rabies vaccines and return on the same flight.

What she knew of Rupununi was based on a project she had worked on about Guyana when she was in Jamaica.

“Lethem was Rupununi and Rupununi was Lethem to me. When the plane landed at Annai, on its way to Lethem, I was fascinated. The Geography of Guyana told me about the savannahs but there I was seeing mountains,” she said. “It was beautiful. While loading peanuts onto the plane, I asked the pilot if I could get out and look about. I was enjoying the view when I heard a voice say, ‘Dr Pilgrim?’”

She was confused because she knew no one there. She had never heard of Annai until the pilot mentioned the plane was stopping there. It turned out she was supposed to get off the plane there and the horse whose brain she was to take back to Georgetown was not dead. She and the agricultural officer who met her put the horse down. She could not catch the return flight to Georgetown that day.

“We went by tractor to Lethem and that was a journey to remember. I ended up spending a week in Lethem with no change of clothing until the next flight. A kind woman was willing to keep me at Lethem at her home. All I could’ve done was wash my clothes every night as best as I could and let them dry as much as possible and then go out the next day to work in the fields. It was sweat, cow dung and God knows what,” she recalled.

That was in November 1985. Some 25 years later, while talking with her swim colleague Stephanie Gomes-Fraser, she learned that the woman who assisted her was Stephanie’s sister.

Pilgrim said, “I firmly believe that everyone in Guyana is related, maybe not by blood, but in one way or another. I don’t understand how any Guyanese can be racist. Stephanie was saying that her sister Cynthia and her husband Malcolm were coming to Georgetown. I asked her, ‘Was Cynthia a teacher?’ Cynthia rescued me for that whole week.”

After her Rupununi experience Pilgrim asked to be posted to Lethem to work as a veterinarian.

“If I have one regret in my life, it is that the then chief agricultural officer said he was not sending a single woman to Lethem. I think he was very wrong to do that. That was the one decision that ended up with me never really practising what I was trained for,” she said.

When the three-month apprenticeship period ended, she was appointed to head the Wildlife Division in the Ministry of Agriculture, which had one staff member at the time.

After she was placed in charge, a few more staff were employed. She headed the Wildlife Division, which dealt mainly with the exportation of wildlife at the time, from early 1986 to 1998 when she was advised to leave the job for her safety, and which she did after seeking legal advice.

From then to now, Pilgrim thinks that the wildlife division which has evolved into the Guyana Wildlife Management and Conservation Commission is in a good place with better resources.

“In my time, the challenges were different,” she recalled. “The wildlife trade was going on, on a wider scale, since the 1970s, at least ten years before I came home. By the time I returned, about 16 people were making a substantial living from the exportation of wildlife. Guyana was already a signatory to the CITES [the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species] and through that there was already pressure being put on Guyana to put a quota system in place to limit exports of wildlife or the trade would be shut down.

“A system was also in place for wildlife exporters to deposit all foreign exchange into the Bank of Guyana and not all the wildlife exporters were compliant. For the first time regulations were imposed on them and they felt they were being affected negatively.

“That was a bit of a challenge. The wildlife trade will always have its ups and downs not necessarily because of problems in Guyana, but because of the international nature of the trade and with people willing to pay for endangered species. That is a potentially difficult area to deal with.”

Until the end of March this year Pilgrim was the chairman of the Wildlife Management and Conservation Commission. She was initially appointed to chair the board of the commission by the previous administration. Prior to that, she was on the scientific committee of the board.

After leaving the Wildlife Division in 1998, Pilgrim did not go into private practice. Instead, she worked privately from home also assisting her partner, a medical specialist, in accounting. Her partner has attended to several injured athletes at her request, and free of cost.