But within the choice to reveal that moment months before the film’s public release, I find myself thinking of how this new film, a sequel to one of this century’s most critically acclaimed blockbusters, functions on a restless relationship with its predecessor that weighs on it for too much of its running-time and towards its closing moments. There are various things about Ridley Scott’s return to the Roman Empire that remind us of the director’s thrilling capabilities. But, too often, even the things that work seem too bound to the original film. In many ways, “Gladiator II” feels like a palimpsest of its predecessor.

One decisive way this feeling persists is in that revelation from the trailer. Although the ads have made it public knowledge, indicating that it does not count as a spoiler, this is a warning for those who would like to be completely ignorant to any aspects of the new film: you should not read further.

Derek Jacobi (as Senator Gracchus, a member of the Roman senate) and Connie Nielsen (as Lucilla, the daughter of the former emperor Marcus Aurelius) are the only two performers from the first film to appear in the sequel, but not the only characters. In a heightened moment of tension in the film’s second trailer we see Lucilla call Paul Mescal’s gladiator character by the name of her son (Lucius) and tell him that his father was Maximus, the protagonist of the first film played by Russel Crowe. Although I’m lucky that my avoidance of film trailers left this moment as an in-film revelation for me, it betrays a quality about “Gladiator II” that becomes central to its dramatic effect. In its insistence on binding itself so closely to “Gladiator”, there’s an agitation that soon comes to overwhelm the plot developments of this new film.

After a montage of illustrations of events from “Gladiator”, “Gladiator II” opens not in Rome, but in Numidia. Here we meet Paul Mescal’s Lucius going by the name Hanno, and intent on resisting the treachery of the far-reaching power of the Roman Empire. Like in the first “Gladiator”, Scott centres the opening segments of the film on an energetic battle sequence to acclimatise us into the violence of this era. Hanno and his townspeople try to resist the approaching Roman army, fighting under the guidance of General Marcus Acacius (Pedro Pascal). Unlike the first film, though, this opening battle features a loss for our protagonist. We are not on the sides of the cheering Roman army but those it attacks. An enslaved, and mourning, Hanno is shipped to Rome after experiencing great personal loss in the battle as Rome expands its reaches across the world.

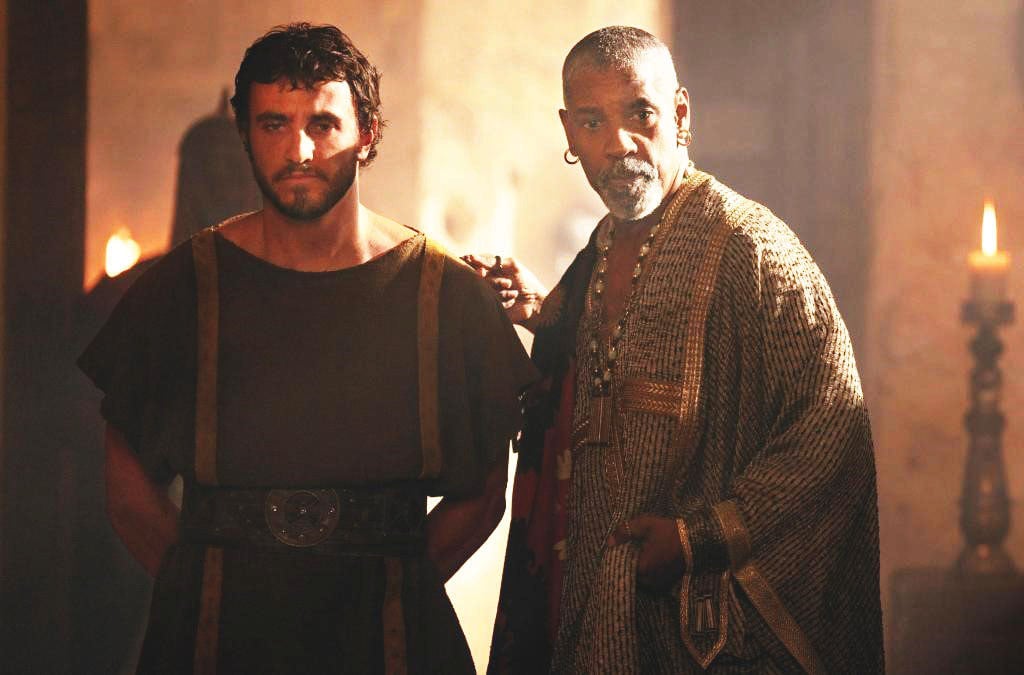

It’s an ambitious and compelling way to open the film, especially on the backs of the predecessor which ended with Maximus’ death as a rallying-call to usher in a new era of Rome where the people have a voice and power. And for much of the first act, John Mathieson’s camera takes great pleasure in reflecting the incongruity between Maximus’s dreams and the currently bifurcated Roman Empire. Poor citizens beg on the streets in threadbare garments while the corrupt twin emperors Geta and Garacalla (Joseph Quinn and Fred Herchinger) throw luxurious parties overflowing with excess. When Hanno is purchased by Macrinus (Denzel Washington), a former slave who has been granted freedom and ascended to wealth, to be a member of his cohort of gladiators the stakes are raised. “Gladiator II” suggests that it might be building up to a politically and ethically complex inquiry into how we think of past societies. It’s an idea that offers a chance to cleverly contrast the decadence of the era with the reality of its harsh dichotomy between the rich and the poor, between the rulers and the enslaved.

This suggestion begins to dissipate as the film moves into its second act. When Connie Nielsen’s Camilla struts into the frame as the wife of General Acacius, unhappy with the ruling class but still a member of it, David Scarpa’s screenplay begins to struggle to make its political ethos legible. And when it suddenly veers into a film emotionally insisting on tying its fate to the legacies of the protagonist from its first entry, even turning Hanno’s character purpose into echoes of Maximus, “Gladiator II” begins to feel less fulsome as a creative work of its own merit and more like a gasping reclamation of its predecessor’s former glory. And it’s a shame when there are numerous potentially engaging arcs lying beneath the surface that offer a different, and more complicated film – one of them is the prioritising of Denzel Washington’s Macrinus. In writing, and in performance, Macrinus is central to the more compelling parts of “Gladiator II”.

Ridley Scott and the entire “Gladiator II” production team are aware of the optics and dynamics of the arc in the film that hinges on seeing Washington’s Black Macrinus buy Mescal’s Hanno and refer to his slave as the key to taking power of Rome. That Macrinus is revealed as a former slave himself adds an element of tension that immediately upsets the dynamics of how we might imagine this world. Even amidst the possibility of nefariousness in the original “Gladiator”, with Maximus as our protagonist the insistence on the possibility of a noble Rome seemed like an imperative part of the audience relationship with that film. When the first half features scenes prioritising Hanno and Macrinus, both with contempt and derision for the customs of Rome, there seems like a sharp possibility of this new film problematising notions of royal lineage, inherent goodness of empire and the power of a chosen one. But it’s a tension that the film cannot believably sustain when it finds itself struggling between the past and the present.

In the most telling scene of the film, Macrinus meets with Lucilla to speak of his past and where he came from. By this point in the film, Washington’s dramatic fervour and intonation have been the most dependable part of the film. Although Nielsen is much better in “Gladiator II” wearing the weight of a grieving mother, she is less electric on screen than Washington who relishes the chance to turn the morally ambivalent Macrinus into a figure of great charisma and dramatic impact. The scene is an important one, for it reveals an important part of Macrinus’s ultimate plan within the film but it’s also important for the ways it forces the script to argue for the power of a monarchy in ways that it cannot articulate. There’s a complicated dilemma that is at the centre of the film when Hanno is revealed to be Lucius. What to make of this Roman descendent growing up with such resentment for the Roman empire? It’s an exciting premise that could offer Mescal so much dramatic weight to play with but it’s one that the film soon recedes from, unwilling or unable to wrestle with the ethical complications.

This complication becomes central to both the plot and spectacle of “Gladiator II” which ultimately seems like a film that is striking as an exercise in its own inability to modulate its intentions and its dynamics. A mid-film scene features a sequence where the colosseum is flooded with water forcing gladiators to fight on ships while sharks swim around them. The moment should feel majestic and thrilling and part of a larger point of the moral rot on display. But like too many ostensibly thrilling moments, “Gladiator II” finds itself unable to render the moment as exciting as it could be. When Hanno first meets Camilla, the moment is a clunky one leaving Mescal over-exerting emotion due to the script’s inability to construct a meaningful relationship between the two grieving characters. The more the film goes on, the more all the things that tie the characters to legacies of those from the first film seem like things that weigh it down more than energise. Even Mescal, who is fine but inconsistent, seems better when the film treats him as a new figure rather than one bound to characters from the original.

But, it returns me to the choice to reveal who Hanno really is in the film’s trailer. Would a random audience member be as initially thrilled to see this new film without a decisive thing binding it to the original? Perhaps not, at first. Yet, one hopes that art is willing to take more risks than the expectations of the audience. “Gladiator II” moves better when it rejects its past and so the film and its performers are unbound by what came before them. That the film’s final battle sets up a dynamic where two characters face off in a man-to-man fight that too easily echoes the good-vs-evil fight of Maximus and Commodus, feels like a film that comes to lose its nerve. All the complicated tensions of this era get whittled down to a story of this idealistic vision of Rome that plays more awkwardly now than it did 24 years ago. There is enough diverting this on screen, but it’s a choice that ultimately leaves “Gladiator II” feeling like it’s too trapped in the past.

Gladiator II is currently playing in cinemas