Indigenous people’s advocate, co-founder of the Guyanese Organisation of Indigenous Peoples (GOIP) and former schoolteacher Colin Klautky, 63, was elected by civil society organisations to sit on the Indigenous People’s Commission in November 2022 and is still waiting to be sworn in.

“That is not good at all. You can’t go through all these democratic processes and then someone is stalling the process for unknown reasons. I’m looking forward to further representing indigenous people on the Indigenous Peoples Commission and this wait is very agonising,” Klautky, the holder of a Bachelor of Arts degree in journalism from the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada, told Stabroek Weekend in a recent interview.

A member of the Multi Stakeholders Steering Committee for the Low Carbon Development Strategy, Klautky said one of his duties is to do outreach activities in indigenous villages and teach the merits of a green economy.

“That is not difficult because of how I put it over. Our ancestors over the last 10,000 years in Guyana practised a green economy. All we are doing is returning to it. Those days we did not have gold and oil extraction going on,” he said.

In recent times, he said, it appears that indigenous people are quite content with receiving cash grants and carbon credits in the name of progress, development and enlightenment.

“These are all short-term things that people cannot depend on. Those funds will run out. Indigenous peoples need to know more than anybody else that if you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day but if you teach him how to fish, you feed him for a lifetime. Right now, I’m noticing a tendency of some people to just throw back in the hammocks and say, ‘We getting cash grant and oil money coming down soon’. That’s the wrong way to think. That’s the Dutch curse coming into play already. We have not learned from the Venezuelan experience or the experience we had with the collapse of the bauxite industry,” he admonished.

He is appealing to indigenous people, especially the youth, not to abandon their culture, their farms that their foreparents had because of the attractions of urban areas.

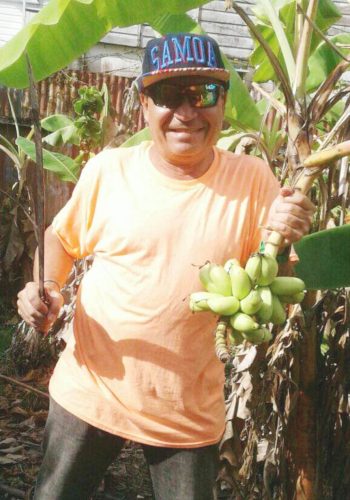

school teacher and mentor

Leonard Fredericks

“We can’t be receiving handouts all the time. Stop waiting for oil money. It may be an illusion. It may never come. You cannot eat gold. You cannot drink oil. You can live off your farm,” he posited.

Klautky has, over the years, since 1990, interchangeably served GOIP for two-year terms, as a committee member, public relations officer, secretary, deputy chief and chief.

He is the GOIP’s representative on the Caribbean Organisation of Indigenous Peoples (COIP) which is headquartered in Trinidad and Tobago. He also represents GOIP and COIP at international forums and during representation over the past three decades he has travelled to 21 countries at conferences and meetings.

He said the challenge the GOIP now faces is recruiting young people who are interested in issues affecting them and who could fight for their cause with a passion.

Advocacy

He dislikes Guyana’s politics. Klautky said, “It is too divisive. I don’t refer to any political party when I speak. I am non-partisan. I cannot be brainwashed, neither can I be bought. I learned to speak with people I don’t see eye to eye with and listen to them.”

Over the years he joined several picket lines on several issues including the Amerindian Act of 2006.

The Guyana Teachers Union (GTU) advised him to join the protest after working hours and to consult the union if he was threatened.

“I felt covered by the GTU, and I was very much part of protests outside Parliament Buildings on the Amerindian Act of 2006. I thought the act was a bit too paternalistic, that the Minister of Amerindian Affairs had too many powers and it needed modernising,” he stated.

Several things led Klautky to advocacy including the sport of lawn tennis. At Kaikushicabra, he learnt about Evonne Goolagong, an Australian Aboriginal of the Wiradjuri nation who was a former World Number 1 player during the 1970s and early 1980s. He recalled that his grandfather admired her tenacity to stay on top despite her people being discriminated against.

village shop in Great Falls

“From then on, my interest in indigenous peoples began to take shape,” he said.

Leonard Fredericks of the Pomeroon River, a former schoolteacher at Malali, Great Falls and Number 47 Settlement was also one of his role models. Fredericks, who is well spoken, later became a toshao at Great Falls where he lives.

He was first employed by Klautky’s father to look after their family village at Kaikushicabra before he became a teacher and toshao.

Fredericks’s favourite tennis players were Goolagong and Brazilian Maria Bueno – the most successful South American player and the only one to date to win Wimbledon. He wanted to build a lawn tennis court at Kaikushicabra in honour of Evonne Goolagong.

“I thought it was fantastic. I also wondered why we in Guyana do not have indigenous names. I have noted that only the Wai Wais have their first names and surnames in the Wai Wai language,” he stated.

With a developing interest to learn more about indigenous people, Klautky sought out an organisation called the Amerindian Association of Guyana led by educator Ian Melville of the Rupununi in the 1980s to which he aligned himself. It was the only functioning indigenous organisation at the time.

Melville is a member of the Atorai, a branch of the Lokono nation who were found at the headwaters of the Essequibo River. The Atorai nation numbers less than 100 in Guyana, according to Klautky.

In 1990, the Amerindian Association of Guyana changed its name to the Guyanese Organisation of Indigenous Peoples and started to lobby for some changes.

On 12th October1992, which was the 500th anniversary since Columbus’s arrival to these shores, GOIP marked the occasion by throwing wreaths in the Atlantic Ocean as a sign of mourning. That was after general and regional elections were held and civil disturbances had erupted in Georgetown.

“We pulled it off even though people were scared of going out. We mobilised 20 people,” he said.

Klautky contended that GOIP might have had a big role in deciding on the date of the elections. “GOIP wrote then president, Mr Desmond Hoyte asking him not to hold elections on the 12th of October because of its historical significance to Indigenous Peoples. To our pleasant surprise Mr Hoyte announced that the elections would be held on the 5th of October. Guyana doesn’t know much about this,” he revealed.

Amerindian Heritage Month

Another role GOIP played at the time, Klautky said, was in the shifting of Amerindian Heritage Month from October to September. Amerindian Heritage Month began in October 1985 under the Hoyte administration.

He noted that at their first general assembly in July 1990, GOIP resolved to not accept October as indigenous heritage month because of the impact of Columbus’s arrival and subsequent invasion of the American continents that included Guyana. GOIP also resolved to lobby the new government to move heritage month from October to another month.

Then leader of the Opposition Dr Cheddi Jagan met with GOIP’s executive sometime in 1991 to listen to their concerns.

“I give him a lot of credit for this. He wanted to consult with civil society organisations. There was no Ministry of Indigenous People Affairs or other indigenous organisations at the time, so we met with him at Freedom House in Robb Street. He was surprised at our idea to move Indigenous Heritage Month from October to another month. He said he loved the month because Mrs Janet Jagan’s birthday and the anniversary of the Great Russian Revolution were in October,” he recalled

Nevertheless, he told the executive that once elected to office he would do what he could to change the month.

“Today, the origin of Amerindian Heritage Month is somewhat skewed. A lot of people think that the change in the month from October to September was Dr Jagan’s idea or that Amerindian Heritage Month began with Dr Jagan. It did not. If he were alive, he would tell you it didn’t come from him,” Klautky said.

GOIP had suggested November based on a recommendation by Phillip Duncan who had suggested the 1st of November in keeping with the indigenous festival of Wakamuli observed by one of the nations in the Rupununi and in keeping with the North American Indigenous Heritage Month. They also suggested August in keeping with the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples observed on the 9th of August.

“However, we decided by consensus on the month of September in honour of Stephen Campbell, first Amerindian Member of Parliament. Other organisations came on board. September was first commemorated as Indigenous heritage month in 1995. The then deputy chief of GOIP was Minister Vibert De Souza. He was the fourth indigenous affairs minister. The first to hold that portfolio was Stephen Campbell then Randolf Cheeks, both of the United Force, then Phillip Duncan of the People’s National Congress. De Souza wasn’t the first minister to hold that portfolio like people are being taught,” Klautky posited.

Ancestry

Klautky was born in Georgetown, but he spent all his early school holidays in a small family village, Kaikushicabra, next to Malali Village in the Upper Demerara River, Region Ten. Kaikushicabra is an Akawaio word meaning Creek of the Jaguar.

At Kaikushicabra his father, Claude Klautky, ran a timber business. The entire area was once occupied by the Makushi people until many Lokono (Arawak) people migrated to Malali and surrounding areas during the past century mainly to work in timber, the area’s main livelihood.

“Although I had my formal education in Georgetown, I learnt an awful lot in Kaikushicabra. It started to shape my interest in indigenous and world issues. I learnt about life there, to swim, and to swim against the current in the real world which led me to advocacy on behalf of indigenous people who need help in education, self-empowerment and so many other things,” he observed.

The origin of the name Klautky, he said, was hazy. “My great grandfather Ewald Conrad Hermann came from Europe as a land surveyor. He had a long surname that was difficult to spell and so he shortened it to Klautky. Everyone whose surname is Klautky on Planet Earth today would be related to each other.

Klautky’s great grandfather came to Guyana to survey the Guyana-Venezuela border for the 1899 border settlement.

“He didn’t return to Europe and settled here. I am one of his descendants. As a descendant of a surveyor of the boundaries, without doubt, I am on the side of the 1899 agreement,” he stated.

Klautky is not sure of his paternal grandmother Christina’s indigenous ancestry. She was born at Tibicuricuyaha just above the Malali Rapids and was the first indigenous woman to run a timber business in Guyana in the 1950s. According to different versions, from the late Dr Desrey Fox, the Williams family of Great Falls, the Klautkys and Ashbys from Upper Demerara River, it was possible she was mixed with Akawaio, Patamona and Lokono, or a mix of any two or just one. She died when Klautky was 10 years old, but he has happy childhood memories of her.

His maternal indigenous ancestry is of the Karina (Carib) people from Agatash on the Essequibo River. “Because of my maternal grandmother’s ancestry, I tend to identify more with the Karinas. I am trying to see how the Carib language could be revived. In Guyana it is facing extinction. Only in Baramita, people speak the language,” he lamented.

It was also noted that some of the Carib people at Kwebana on the Waini River also speak the Carib language where teacher Althea Harding is compiling a Carib dictionary.

“The younger people need to show interest in the language for it to survive. That is one of my roles in indigenous advocacy, the preservation of the Lokonos, Karinas and Warrau languages, the three main coastal indigenous nations in Guyana,” he said.

From Kaikushicabra, his father moved his timber operations to Number 47 Miles Settlement in Mabura Road.

“As a matter of fact, my father, whose nickname was, ‘The Greenheart Factor’ or ‘Uncle Nedd’, founded the Number 47 Miles Settlement. He was a legend. He was very knowledgeable about the trees in Guyana. It was a skill I wanted to learn but he said that was not for me. He wanted me to become a doctor like three of my uncles, but I was not interested in the sciences. I was more into the arts like English, Geography and History in particular,” Klautky said.

The former Queen’s College student left Guyana in 1979 to pursue studies in journalism because he wanted to become a journalist and run a newspaper or radio station. While studying in Canada his parents were encouraging him to stay there. “While in Canada, I realised I didn’t want to live there because the lifestyle was not compatible with what I wanted. I worked at the radio station at the University of Western Ontario, and I read morning news at 6 am,” he recalled.

On his return to Guyana, he did not want to work with the state-controlled media.

Through contacts, his father secured a job for him at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs where he worked from 1985 to 1989.

“It was a nice job working in protocol, but the environment was too politically charged. I could not survive there as a diplomat. I couldn’t turn a blind eye to some of what I considered were wrongs. It was interesting interacting with staff from the diplomatic missions stationed here and attending receptions at various embassies,” he said.

In between jobs, and every opportunity he got he spent in the Upper Demerara River.

Teaching

He was a schoolteacher from 2000 to 2010 and taught Caribbean History, English Language, English Literature and Social Studies at St John’s College. While teaching Caribbean History, he realised that the history curriculum in schools needed updating, especially with regard to indigenous people.

“It was very difficult, especially when I had indigenous children in the classroom, to refer to foolishness like Columbus discovering the region and so on,” he said.

Referring to indigenous nations like the Lokonos as Arawaks and the Karinas or Kalinagos as Caribs, he said, are misnomers.

After teaching according to the textbooks, Klautky said, he held a ten-minute informal session where he told the students things like, “We’re not nine Amerindian tribes, we are nine indigenous nations. We are Lokonos, not Arawaks. We are Karinas and not Caribs.”

He also taught students the original indigenous names and meanings of all the Caribbean islands. “Those are not on the official curriculum of CXC history which is very shameful. All the students, not only indigenous, were very interested. For example, the original name for St Lucia is ‘Hewanura’ which means Island of Iguanas, and ‘Waitukubuli’ for Dominica, which means, ‘How tall is her body’. Both are Kalinago words.

“We need to de-Columbise the language, the vocabulary in the Caribbean history books because some of what students are learning is very outdated and colonial. If we are talking about transformation from colonialism to independence, all this must be part of it.”