There was a period between the 1960s and early 1970s that was an age of super-heroes in film – specifically in the cinema and television. Before that there was the reign of the pantheon of super heroes who appeared in comic books and then in films – Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and the super detectives like Dick Tracey who commandeered the imagination of the youth, and, for a slightly older audience, the popular novels such as other geniuses in crime detection, private detectives Mike Hammer and Donald Lam.

There was a period between the 1960s and early 1970s that was an age of super-heroes in film – specifically in the cinema and television. Before that there was the reign of the pantheon of super heroes who appeared in comic books and then in films – Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and the super detectives like Dick Tracey who commandeered the imagination of the youth, and, for a slightly older audience, the popular novels such as other geniuses in crime detection, private detectives Mike Hammer and Donald Lam.

Modern society was rapidly changing with the fast moving advance of technology that fueled science fiction, but that appealed to the imagination and drove endless fantasy in fiction and on the screen. But in real life there was the rise of make belief with the creation of characters and situations that sensationalised a future technology with scientific wonders that were just slightly beyond belief because the society was developing so rapidly that they could nearly be true. The super hero genre was driven by a mentality that believed these wonders would soon be happening in reality.

Little has changed today, nor have there been any revolutionising of the trends over the past thirty or forty years. Take for instance the rise of the likes of Sidney Sheldon, with international secret agents (a development on the James Bond type?) men with razor sharp brains and incredible training, who perform miraculous escapes and win impossible moral battles. The same waves brought on the rise of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and such TV series as the “Game of Thrones”, “Stranger Things” or “Walking Dead” – the shape of these shifting forward as modern science advanced further and the fictitious creations on screen or on the page adjusted to excite the mind of the contemporary youth, characterised by wizardry at technology.

Little has changed today, nor have there been any revolutionising of the trends over the past thirty or forty years. Take for instance the rise of the likes of Sidney Sheldon, with international secret agents (a development on the James Bond type?) men with razor sharp brains and incredible training, who perform miraculous escapes and win impossible moral battles. The same waves brought on the rise of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and such TV series as the “Game of Thrones”, “Stranger Things” or “Walking Dead” – the shape of these shifting forward as modern science advanced further and the fictitious creations on screen or on the page adjusted to excite the mind of the contemporary youth, characterised by wizardry at technology.

The inventions in science fiction are often so amazing that many believe this genre is a contemporary development. Actually, it is much older than is generally acknowledged. Of course, the works of Robert Louis Stephenson, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), or H.G. Wells, The Invisible Man, (1897) will immediately be remembered, but it is even older than that. There were the works of Frenchman Jules Verne (1828 – 1905) who wrote novels such as Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1869-70) and Journey To The Centre Of The Earth (1867). Yet, it goes back even earlier, before Verne was even born, to one of the most amazing novels in English fiction for its depths in modern science fiction and feminism, Frankenstein (The Modern Prometheus), published in 1818 by Mary Shelley, the 20 year old wife of Romantic poet Percy Shelley. These were all made into films in the 1930s and later.

Super Heroes

The wave of comic book super heroes in the 1950s and 1960s could well have been the Freudian products of the mind of the western world, especially American, seeking regeneration after World War II, which ended in 1945, leaving many repercussions. These included its aftermath, the Korean War and the Vietnam War, with the lingering sentiments of nationalism, patriotism, heroism and triumph. These might well have reflected a kind of vicarious victory, the wishful thinking of a devastation of enemies by American heroes at a time when the cold war was strong and getting hotter. Similarly, the imagination of the British , on the verge of relinquishing an empire that gave them a sense of power and very much an ally of the USA in the cold war, conjured up super heroes who asserted the greatness of Great Britain (James Bond and Simon Templar, for instance).

This evolution of the super hero genre is to be noted. Superman, himself, led the standard type that goes all the way to Captain Marvel. There were heroes with totally fictitious, even magical, super-human powers that were totally unreachable for ordinary mortals, who then celebrate triumph of good over evil vicariously. The superman heroes are patriotic and moral. But then, there emerged heroes who were quite human and mortal, but who possessed mental and physical prowess beyond the normal or average. They are on the side of law and order, they outwit and overpower crime and criminals, as well as foreign spies, agents and communist governments. Unlike Superman, they come much closer to ordinary humans with no super powers, but their weapons are brain power, honesty and patriotism. They are brilliant secret service agents, detectives and lawyers. Who appeared in the 1950s, like Dick Tracey.

James Bond and The Saint

James Bond is the best known and most popular of these adventure series. Bond appeared in a comic strip series published in London’s The Daily Express between 1958 and 1977. It will surprise many that the newspaper comics predated the famous James Bond films because of the immense popularity and success of the films which are known throughout the world and have been exceptional hits at the box office. Both the films and the comic strips emerged in the super hero era and would have done a great deal for the British ego, heroism and social satisfaction.

Bond is too well known to bear repetitive detailed description here, but he is among the very early superheroes of the era. Unlike Superman, he is one of those who do not have extra-human powers, but is an extraordinary mortal, almost invincible because of his high-powered training as a secret agent, his superior mind and his genius at physical combat. Significantly, he surpasses other secret agents of popular fiction as created by Sydney Sheldon. To add to popular audience delight he is exceptional as a ladies man, is witty and has a sense of humour.

While the Daily Express features began in 1958 with Casino Royale, the series of films only started with the release of Dr No in 1962. It saw immediate success with Scottish actor Sean Connery playing Bond, who created the role in outstanding fashion, making it difficult for those actors who came after. Of those, however, Roger Moore, also British, did very well in the continued success and popularity of the character.

What is more, Bond has greater depth than his popular appeal. The character, the comics and the films are all adopted from the series of novels by English writer Ian Flemming, who produced the first Bond novel, Casino Royale, in 1953. That was at the height of the anti-communist era and the acute consciousness of the west for heroism and conquest in the world power struggle. Victory in the world war would have been still fresh in English consciousness and a character like 007 would have fired the imagination as a good representative of a triumphant United Kingdom.

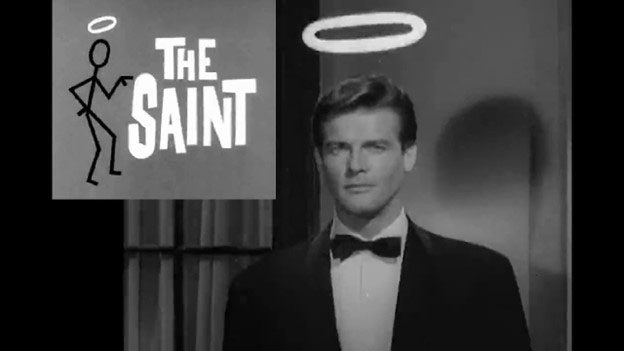

Simon Templar, commonly known as “The Saint” is a fairly similar 007 type character, the hero of a television series carried on ITV in the United Kingdom between 1962 and 1969. This series is dominated by the infectious personality of Roger Moore who created the role of The Saint. Also well known, he, too, is an ordinary mortal, made extraordinary by his unsurpassed skill as a private investigator with superb mental agility, intelligence and will hold his own in any fight. He resembles Bond in his prowess with the ladies, his wit and good humour.

It is, perhaps, because of this 007 similarity that The Saint lives in the secret service agent’s shadow. Yet, as a character, he predates Bond and has maybe more literary depth. He was created in the novels and short stories of British writer Leslie Charteris whose first Saint novel came out in 1928. Charteris continued to write and to collaborate with other writers until 1983. The hero has an infamous reputation all over Europe as a villain, but very often surprises his antagonists with his moral strength and consistent honesty. Moreover, he is a patriot and fighter on the side of honour and humanity at a time in the 1930s when despotism and anarchy was on the rise in Europe, leading to the world war. Charteris would have then joined the nationalistic heroic trend that prevailed in the decades after the war.

The Ideal Detectives

A quite different style of private sleuth is the one who became the most celebrated as the best detective of all times – Sherlock Holmes, whose name has become synonymous with the investigation of crime. The Holmes film series is based on the exquisite, accomplished work of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle of the UK – a fictional series written between 1892 and 1908. No crime is beyond the ability of Holmes who can find solutions to the impossible. These creations in English literature show how far back in history detective fiction goes.

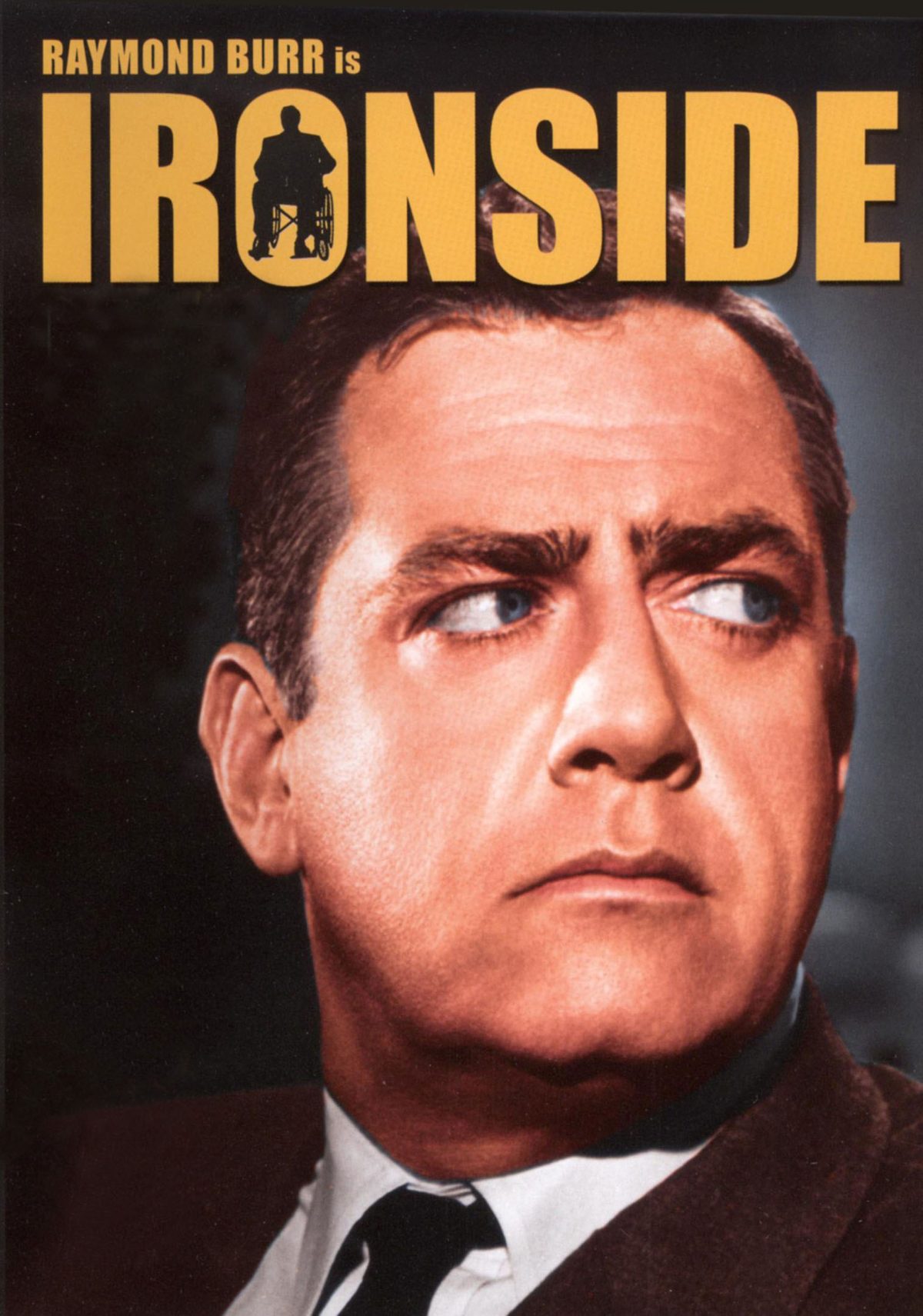

Over on the other side of the Atlantic the trend was similar in the rise of heroic TV series. Among them was the series “Ironside” aired first on NBC in the USA between 1967 and 1975. Adding to the fame of the feature was outstanding movie actor Raymond Burr who created the role of Chief Robert T. Ironside, Consultant to the Commissioner of Police in San Francisco. His history is that while serving as Chief of Detectives he was gunned down by assassins and left paralysed. He was then appointed Consultant and functions as the best of the sleuths despite his disability. He moves around in a wheelchair, but is so agile, swift moving and adept at defending himself that the audience easily forgets this.

Ironside heads a unit of detectives famous for their loyal, efficient, incorruptible service. He joins the cast of mortal, human super heroes, and emphasizes the point even more because he is confined to a wheelchair. There is this American sense of “and justice for all” that this heroic, dedicated character stands for and with which the USA would like to identify. He is equal to none in his sharpness, his uncanny intelligence and investigative skills, which qualify him as belonging to those heroes with extra powers, qualities that appeal to the audiences.

In a similar capacity is Lieutenant Columbo of the Los Angeles Police, a detective with powers of intelligence, observation and deduction beyond the normal. He, too, is played by an acclaimed actor, Peter Falk, who reigned supreme in series that ran on America’s NBC from 1971 to 1978 . Among the qualities that endear him to the audiences is his brand of eccentricity, deceiving his adversaries with his apparent absent-mindedness and a simplicity that leaves his antagonists fooled in a false sense of security. Columbo never fails to solve every murder and defeats every murderer who is arrogant, who insults and under-estimates him.

Again, this is a TV series that appeals to the American pride and the association of the American dream with perfection and the triumph of good over evil. Those themes accompanied the rise of a number of series on television showing smart lawyers like Perry Mason (at one time, also played by Raymond Burr) and Matlock. These are legal luminaries with a genius beyond the normal who will fight for and win an acquittal for innocent clients whose cases appear hopeless right down the wire to the last possible minutes in court. They help the American to feel that “justice for all” really works in their legal system.