On the anniversary of the passing of Martin Carter and the 70th anniversary of the publication of Poems of Resistance from British Guiana, Gemma Robinson revisits Carter’s work.

When Lawrence & Wishart published Martin Carter’s Poems of Resistance from British Guiana 70 years ago this year, their sights were on anticolonial struggles in the Caribbean. The same year, 1954, the London-based publishers had brought out Cheddi Jagan’s Forbidden Freedom, charting the inequalities of Guyana’s working population and the birth of the People’s Progressive Party. Lawrence & Wishart’s catalogue for that year heralded Carter as ‘the foremost poet of the Caribbean people [. . .] a true people’s leader’.

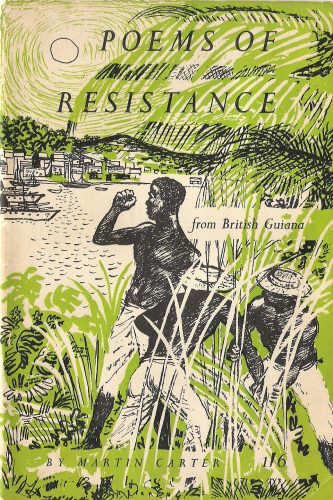

At the centre of the Lawrence and Wishart front cover is an image of a male sugar worker. He is half-turned to the viewer with his chest facing us, twisting towards the water with a raised fist. Next to him are his comrades bent over at work. In the distance are ships that recall not only the vessels that transported sugar from the estates, but also the tense moment of invasion in 1953 that brought British troops and warships to control the State of Emergency.

The man’s raised fist reminds us of Carter’s poetry of anti-colonial rebellion and The Communist Manifesto’s rallying cry ‘Workers of the world, unite’. The cover would certainly have reminded some readers that Carter had been arrested at Plantation Blairmont in 1953 with other PPP members for “spreading dissention” among the agricultural communities. For some the book cover might have registered that this middle-class poet was extending his poetic voice to the workers whose life he hadn’t lived – that he was seeking comradeship with the African Guyanese and the Indian Guyanese workers whose exploitation on plantations could be traced from the past of slavery and indentureship into the present.

The man’s raised fist reminds us of Carter’s poetry of anti-colonial rebellion and The Communist Manifesto’s rallying cry ‘Workers of the world, unite’. The cover would certainly have reminded some readers that Carter had been arrested at Plantation Blairmont in 1953 with other PPP members for “spreading dissention” among the agricultural communities. For some the book cover might have registered that this middle-class poet was extending his poetic voice to the workers whose life he hadn’t lived – that he was seeking comradeship with the African Guyanese and the Indian Guyanese workers whose exploitation on plantations could be traced from the past of slavery and indentureship into the present.

As I look at the cover and Carter’s poems again on this 70th anniversary of Poems of Resistance, the importance of human struggle remains powerful, but something else comes into focus. In the unattributed artwork, the monochrome figures are entangled in their landscape. The block prints of green are dynamic alongside human activity, suggesting sugar cane, ferns, rainforest vegetation, with energy fields swirling out from the sun. The anonymous artist had perhaps spotted something in Carter’s poetry that many readers have missed. That Carter’s world is attuned to the human, but it is not human-centric. Rather, to use Malcolm Ferdinand’s phrase, Carter’s poetry is part of a ‘worldly ecology’, where the world is ‘an open whole, comprising human affairs and the planet Earth with its landscapes, its fauna and its flora’.

Ferdinand’s work in A Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World is part of a diverse tradition of seeing how forms of domination exploit all forms of living and being in the world. Politicians might engage in a discourse of ‘worldly ecology’, but it is still uncertain if the Belem Declaration of last year will show that the Amazon basin can be protected through regional politics. Janette Bulkan, Roshini Kempadoo and Alissa Trotz’s 2023 report on ‘Guyana’s Oil Dorado’ makes clear that ExxonMobil oil extraction in Guyanese waters is one more chapter in a global history of exploitation: ‘The fabled city of El Dorado has materialized today as Oil Dorado’.

As citizens and lawyers use community action and Guyana’s robust 1996 Environment Protection Act to challenge the oil and gas sector, Bulkan, Kempadoo and Trotz encourage us ‘to engage in a conversation that questions Guyana’s extractivist model that pins the country’s hopes yet again on the short-term and reckless plundering of resources’. Ferdinand’s call for us to recognise and support ‘a decolonial ecology’ is at the heart of this conversation, and Carter’s poems of resistance anticipate this demand for layered perspectives. In other words, Carter’s poetic attention to the injustices of a colonial society involves more than attending to people. As we look again at Poems of Resistance from British Guiana, Carter’s decolonising, ecological vision emerges as central to his hope for the liberation of his colonized home.

‘Green and wide and free’

If we want to reframe Carter’s political poetics as ‘green’, we can also be quite literal when we look at his work. This is because the colour is a prominent word in Carter’s poetry: green is the colour that features most frequently, from his earliest poems to his final pieces. In ‘Bitter Wood’ (1993) he writes gnomically of ‘the green sight / of the freedom of a tree’. In the opening lines of To A Dead Slave (1951) Carter writes with less compression:

I only want

to heat these pages with my own heart’s fire,

to touch these hearts that live beside me here,

to hasten birth, to drive the shadows back,

to free the memories shackled in the mind,

to raise a beacon in these smoky nights,

to follow rivers from the shore and creek

until this land is green and wide and free.

Carter’s writing is twinned with the greening of the ecosystem he lives in. Liberating the place and its inhabitants from their colonial past go together – in politics and in poetry. The hope for a green, wide and free environment could never be just metaphorical in a place where history showed Carter the relationship between indigenous genocide and land appropriation, and the deadly costs on enslaved and indentured populations who dug out and maintained Guyana’s empoldered coastline and riversides. Colonialism’s plantation landscapes had devastated the region’s diverse ecosystems in pursuit of the monoculture of sugar.

In Poems of Resistance from British Guiana, greenness alerts us to many things.

Hope and the future are green

In Carter’s work hope and hope for the future can be framed as green. Sometimes this hope is rendered fragile and surreal as in the memorable early lines of ‘University of Hunger’: ‘The green tree bends above the long forgotten / The plains of life rise up and fall in spasms / The roofs of men are fused in misery.’ Greenness here is resilient resistance to compromised existence, a sign of life but one weighed down or pulled towards ‘the long forgotten’. The poet’s iconoclastic gathering of nouns and verbs implies his immersion in a landscape, apparently seeking to learn in a ‘university of hunger’ that is attended by humans and more-than-humans alike.

Carter’s fifth verse refuses species in favour of an allegiance to ‘the dark ones / the half sunken in the land’. Read through an ecological lens, these lines don’t speak of the less-than-human but of all existence decimated by the ‘wide waste’. Fred D’Aguiar has described the poem as a ‘trek through the country’, and the refrain – ‘O long is the march of men and long is the life / And wide is the span’ – reminds us of lives lived within an era that Carter calls ‘the terror and the time’. But Carter’s return to the idea of the long and wide span of life need not only lead us to terror. It can also lead us to the more-than-human, to resistance against devastation and back to the persistent but obstructed green freedom imagined in ‘To A Dead Slave’.

The hopefulness of a green future is tied in Carter’s work to achieving equilibrium within a shared environment. In ‘Let Freedom Wake Him’ he writes:

Comrade the wind is sweet with eucalyptus

Early at morn green grass reflects the sun

Here in my home my little child lies sleeping

Let freedom wake him – not a bayonet point.

The poem focuses on the poet’s baby son, but notice how the idea of freedom and comradeship makes sense through the smell of the eucalyptus tree and the photosynthesizing grass. The ‘bayonet point’ (a symbol of exploitative deadly technology) is so out of place on the page that it must be emphatically separated from the rest of the poem. The multisyllabic words of ‘bayonet’ and ‘eucalyptus’ stand out against the simple mostly monosyllabic language, and they are the two poles of Carter’s world.

Sensing small moments of radical greenness

Poems of Resistance from British Guiana may be a short collection of eighteen poems but across this work readers can find an obliterating critique of colonialism, a political affirmation of better times to come, a lyrical description of life lived lovingly within the environment, and an elegiac dream that recognises the fragility of a fully decolonised freedom. In ‘The Knife of Dawn’ (also known as ‘The Kind Eagle’) we find all these impulses. What Carter does so well is to play with scale and realism in the poem. His canvas stretches from the individual, to human constructions, into the cosmos and to the green ground level:

I make my dance right here!

Right here on the wall of prison I dance

we who are sweepers of an ancient sky

discoverers of planets, sudden stars.

we are the world’s hope.

And so therefore I rise again I rise

again freedom is a white road with

green grass like love.

Eusi Kwayana has noticed how Carter’s metaphors are created from multiple layers where one thing is likened to another thing and then another. Here freedom is ‘a white road with green grass’ and it is also like ‘love’. Walt Whitman, a poet who Carter read, calls grass in ‘Song of Myself’ ‘hopeful green stuff’ and some of this everyday energy is present in Carter’s work, where freedom, like love, might be found as we forge our ways in the world.

In ‘Death of a Comrade’ Carter mourns the death of Ivan Edwards, a PPP comrade who died while swimming off the coast of Barbados. The first verse speaks of the mark of death on people, but the second offers us a moment of radical revisioning that supports the scarlet banner and the mourning vanguard, and makes sense of the loss of life and community:

then let me take

a patience and a calm –

for even now the greener leaf explodes

sun brightens stone

and all the river burns.

At this time of loss, the ‘greener leaf’ reminds us of ways to see more. As Carter’s human emotions are trained into patience and calmness, they give way to another consciousness that is dynamic (exploding, brightening, burning), one that can hold and make sense of human mortality. The final line, ‘Death will not find us thinking that we die’, is a monumental statement that emerges from sensing small but radical moments in nature.

Green ancestral protection

The story of Carter’s resistance poetry can be extended with a poem that was excluded from Poems of Resistance from British Guiana. Correspondence held in the University of Chicago between the Dutch editor Paul Bremen and American poet, Walter Lowenfels, discusses a manuscript that contained three extra poems. This extended manuscript is currently lost, but we know it included the poems ‘Where Are Those Human Hands’, ‘Do Not Stare At Me’ and ‘Ancestor Accabreh’. We can only speculate why these poems did not appear in the 1954 collection, but in an interview Eusi Kwayana remembered Carter’s sustained interest in writing about Accabreh, one of the leaders of the Berbice Rebellion of 1763. In ‘I Clench My Fist’ it is ‘ancestor Accabreh’ who the poet summons to help him resist the ‘British soldier, man in khaki’.

Carter and his PPP comrades had been researching rebellions in the Guianas and Carter had written about the examples of Berbice and Demerara in his articles in the PPP magazine, Thunder. Research by Marjoleine Kars on the rebellion casts Accabreh (also known as Accabiré and Accabre) as a leader hoping to lead a maroon life. When he was captured after the year-long revolt, it was in a 50-hut village that had been constructed on an island in a swamp near the Berbice River. It is not clear if Carter knew about or imagined this marronage, but the poem begins with the denouncement of lethal plantation technology over the protections of ‘green shelter’:

Was ancestor Accabreh

was ancestor himself

he stand up like a palm tree

his head touch the sky.

Was ancestor Accabreh.

He said no more the grey chimney no more

no more the cold wind no more no more

He said, when I come back

O green shelter of long grass

hide me forever and ever.

He said , O woman face of earth

when I come back

let me lie down

kiss me to sleep

He said when I come back

in the green shelter of darkness

let me lie down in peace.

The combined powers of ‘green shelter of long grass’ and ‘woman face of the earth’ are invoked as ancestral protectors, mirroring and extending the poet’s summoning of Accabreh in ‘I Clench My Fist’. The human is revealed as always belonging to the more-than-human world. While we might question a dynamic of a caring and feminised land in the service of male activity, in this poem it is non-masculine powers that Accabreh recognises as nature’s loving ‘naked’ forces that negate exploitative, extractive action:

But before he died he laughed.

He said, O green shelter of long grass

O woman face of earth moving from side to side

Be naked for my children as for me

Accabreh! Accabreh!

Entangled Ecological Thinking

In times when it is hard to sustain outrage in the face of a world increasingly defined by injustice and a politics of death rather than love, Carter’s poetics are as urgent as when they were published 70 years ago. Just as the workers on the front cover of Poems of Resistance are entangled in their environment, Carter’s entangled ecological thinking about the Caribbean world can provoke and guide us. This means that we will continue to grapple with the worldly vocabulary of humanity that appears in this exceptional collection: Carter’s university, yard, prison, hospital, ship, market, street, orphanage, comrade, ancestors, slave, man, woman, soldier, cartman, fisherman, mapmaker, grandfather, wife, mother, father, children. But now we know we must also look for his vocabularies of the more-than-human – their capacities for freedom, shelter, care – and remember that Carter’s resistance was always green.

Gemma Robinson is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Stirling, Scotland, and the editor of University of Hunger: the Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe). The collection includes the full text of ‘Ancestor Accabreh’.