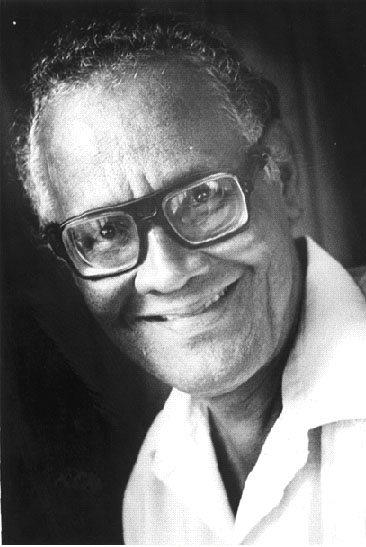

In keeping with the practice of annual tributes to the greatest Guyanese poet, often called the National Poet, every June and December, “The When Time” was presented by the Moray House Trust, and featured selections from the 1977 collection read by various voices and moderated by Isabelle de Caires.

The poems reproduced here include some from that group recited on Friday and others from other periods in Carter’s career, marking a mixture of different preoccupations. They come from as early as the 1950s and from his later works in the 1980s, giving an idea of the variety and of different types and interests. For example, note the stark contrasts in the ‘title poem’ from 1973, “The When Time”, and an early selection from the 1950s “Tomorrow and The World”.

The kind of expansive optimism and celebration of brotherhood and a bright, happy outlook, fraternity with everyone, an upbeat tone singing harmony between different classes of humankind and between them and the inspiring natural environment characterise “Tomorrow and the World”.

This is an interesting and rare side of Carter certainly not reflected in the tragic tones of “The When Time” or of “They Say I Am”, or even another poem personifying the fragmented, fractured Georgetown landscape “The Leaves of the Cana Lily” (not printed here), which belongs to the “When Time” group.

“The Poems Man” is a fascinating bridge between the two types and it may even be said to be more celebratory than the predominant darkness in Carter.

It is existentialist and contrasts states of being represented by the little girl at her age and stage in life “going” some place as against the mature man “coming from” somewhere else. There is the suggestion of futuristic youth as against experience, but they meet symbolically, on a bridge and they are linked by the celebration of the man who creates poetry. But one needs to be careful in reading the “frail bridge” in the poem. It is Guyanese language – in Creolese (Guyanese Creole) a bridge is a gateway leading from the road into someone’s yard.

It is the same language in which Carter invents the term “poems man” – in the little girl’s creole consciousness he is a man who makes poems (the word “poet” does not exist in the Creole language).

This linguistic use is typical of Carter. The amazing celebration in the poem is that a 12 year old girl in the countryside could recognise Carter as a poet.

Of interest also is the poem dedicated to Trinidadian poet Eric Roach, who killed himself by drinking poison and wading out into the sea in 1974. Roach, a contradictory and troubled figure, wrote about slavery and wrote powerfully about the fading away of African traditions in Trinidad, but was deeply troubled by the new waves of post-colonial poetry about the bitter legacy of slavery, blackness and suffering in the Caribbean.

Carter celebrates him in the “When Time” collection by invoking the beauty of the Guyanese Amerindian riverain environment side by side with the Georgetown landscape outside his window merging it with the “frangipani” flower and “pain”.

The When Time

In the when time of the lost search

behind the treasure of the tree’s rooted

and abstract past of a dead seed:

in that time is the discovery.

Remembrance in the sea, or under it,

or in a buried casket of drowned flowers.

.

It remains possible to glimpse morning

before the sun; possible to see too early

where sunset might stain anticipated

night. So sudden, and so hurting

is the bitten tongue of memory.

(1973)

The Poems Man

Look! Look!” she cried, “The Poems Man!”

running across the frail bridge

of her innocence. Into what house

will she go? Into what guilt will

that bridge lead? I

the man she called out at,

and she, hardly 12,

meet in the middle, she going

her way; I coming from mine.

The middle where we meet

is not the place to stop.

On the Death by Drowning

of the Poet, Eric Roach

.

It is better to drown in the sea

than die in the unfortunate air

which stifles. I heard the rattle

in the river; it was the paddle stroke

scraping the gunwale of a corial.

Memory at least is kind; the lips of death

curse life. And the window in the front of my house

by the gate my children enter by, that window

lets in the perfume of the white waxen glory

of the frangipani, and pain.

.

(1974)

They Say I Am

.

They say I am a poet write for them:

Sometimes I laugh, sometimes I solemnly nod.

I do not want to look them in the eye

lest they should squeal and scamper far away.

.

A poet cannot write for those who ask

hardly himself even, except he lies;

Poems are written either for the dying

or the unborn, no matter what we say.

.

That does not mean his audience lies remote

inside a womb or some cold bed of agony.

It only means that we who want true poems

must all be born again, and die to do so.

.

(1960s)

Tomorrow and The World

.

I am most happy

as I walk the seller of sweets says “friend”

and the shoemaker with his awl and waxen thread

reminds me of tomorrow and the world.

.

Happy is it to shake your hand

and to sing with you, my friend.

Smoke rises from the furnace of life

– red red red the flames!

.

Green grass and yellow flowers

smell of mist the sun’s light

everywhere the light of the day

everywhere the songs of life are floating

like new ships on a new river sailing, sailing.

.

Tomorrow and the world

and the songs of life and all my friends –

Ah yes, tomorrow and the whole world

awake and full of good life.

.

(1950s)