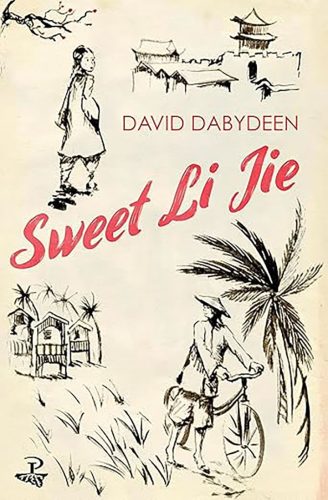

[David Dabydeen, Sweet Li Jie, Leeds, UK, Peepal Tree Press, 2024. £10.99; 166 pp.]

[David Dabydeen, Sweet Li Jie, Leeds, UK, Peepal Tree Press, 2024. £10.99; 166 pp.]

“The British and other foreigners came. There was a sudden collapse, all we built over centuries suddenly collapsed. We were all reduced to coolies, circus performers, concubines, customers, Christians.” – Tang Yu, 1860

“The Negroes have left, but my lands are now lush with coolies.” – Sir John Gladstone, 1838

“Was there a garden or was the garden a dream?” – Jorge Luis Borges

David Dabydeen, Guyanese, West Indian and British prize winning poet and novelist, placed these three inscriptions at the front of his latest fiction, Sweet Li Jie, published by Peepal Tree in 2024. The first is from a Chinese court official, in a dismal summary of the state of his country after the Second Opium War in 1860. The second is a self-congratulatory gloat by Sir John Gladstone, plantation and slave owner, on August 1, 1838, in a letter to his son, William, later prime minister of England. The third is a lyrical reach for inspiration by a Latin American writer.

Gladstone looks with satisfaction at his achievement after founding the disreputable institution of indentureship that brought Indian and Chinese labourers to Guyana, writing his letter, ironically, on Emancipation Day, 1838, when the equally infamous era of slavery was brought to an end. Tang Yu laments the conditions in China that drove many away to brave the wide ocean and journey to join the Gladstone experiment in a quest for precious stones and prosperity in British Guiana. Against that uninspiring backdrop, Luis Borges, much like the indentured servants, the coolies in the West Indies, hopes for a dream to become a reality, for the amelioration of a garden to ennoble the existence of the downtrodden.

These quotations very effectively set the stage for a novel of greed, savagery and plunder, but a most accomplished document of human compassion; a literary masterpiece which takes us through a complex and breathtaking drama, bringing together the histories of China, Guyana, and India in the nineteenth century. Characters and nations are tied together by Gladstone’s indentureship scheme to avert labour shortage on Guyanese sugar estates. It follows the fortunes of peasants and workers who flee warlords and murderous marauders in China and pitiful poverty in India, who are enticed by tales of fortune to follow a false hope of gardens of prosperity in British Guiana.

These quotations very effectively set the stage for a novel of greed, savagery and plunder, but a most accomplished document of human compassion; a literary masterpiece which takes us through a complex and breathtaking drama, bringing together the histories of China, Guyana, and India in the nineteenth century. Characters and nations are tied together by Gladstone’s indentureship scheme to avert labour shortage on Guyanese sugar estates. It follows the fortunes of peasants and workers who flee warlords and murderous marauders in China and pitiful poverty in India, who are enticed by tales of fortune to follow a false hope of gardens of prosperity in British Guiana.

Dabydeen tells, in spellbinding fashion, of suitor Jia Yun who steadfastly pursues an elusive hope of marriage to Sweet Li Jie, a peasant girl who has spurned him. He boards the ship to British Guiana, where he inherits his master Yu Hao’s business and makes his fortune as a textile merchant. He writes a series of letters to Li Jie, telling of encounters with character types driven by greed and treachery, but also of his interaction with others such as Harris and Gurr, who are incorruptible examples of noble human beings. Meanwhile back in Wuhan province, China, Sweet Li Jie and her mother Ma Hongniang, with a history of flight from rogue soldiers, war and bandits, are supported and protected by a rich landlord Master Wang Changling.

Sweet Li Jie is a romance, it is an epistolary, it is historical fiction, it is social realism. Dramatic scenes are played out in Wuhan in 1875, in villages in India, on board a ship, in Demerara, Gladstone Town and the rainforests of Guyana in 1876. It is a tale within a tale, intertwining several protagonists and adventures, sometimes of the quality of inter-related Hindu myths. It is the kind of intriguing and captivating narrative that casts a spell on its audience, and such is the skill of the narrator that once you start reading you cannot put it down.

This is a thoroughly Guyanese novel, as it is a novel of China. Sweet Li Jie is West Indian literature at its most fascinating. One of its most enduring features is its engagement with and detailed descriptions of Guyanese landscape, very interestingly and ironically, often depicted through the narrator’s fear of the jungle. Dabydeen achieves enchanting visions and interactions with the Guyanese rainforest surpassed only by Wilson Harris.

The author has contrived to find a fresh, new treatment of Guyanese Indian indentureship and an unprecedented close treatment of the Chinese coolies. This brilliant and important West Indian novel offers a rare in-depth account of Chinese migration and indentureship in British Guiana, as well as of the factors in China that pushed emigration.

Landscape is a major factor of life in the Chinese provinces inhabited by the novelist’s rural nineteenth century characters. Readers are transported on a dramatic excursion through forests, fields, agricultural plots and countryside made familiar and memorable by gripping, powerful narration in a very significant contribution to contemporary Chinese literature.

Sweet Li Jie is Dabydeen’s tribute to China as a writer who devoted five years to living in China in the service of his country. He was ambassador plenipotentiary of the Republic of Guyana to the People’s Republic of China from 2010 – 2015. In a very important geo-political strategy, Guyana established diplomatic relations with China in 1972, adding a political dimension to a colonial history already rich in cultural and commercial interfaces.

As a researcher, Dabydeen would have taken the opportunities for investigation into the history of China in the nineteenth century, especially in the lives of the peasants, agricultural and labouring classes. As an artist this interface between the two countries obviously incited his imagination, driving him to the provinces of China, its traditions, its landscape, its people. The creation of an engaging, intense, emotionally charged novel such as Sweet Li Jie is nothing less than a writer’s tribute to a country that has had an influence on his life just as it has on Guyana, the Caribbean and contemporary world power politics. The author’s tribute is also paid to individuals – real persons he has known whom he honours by their fictionalised presence in the novel. Not for the first time he gives the name Harris to one of the most genuine and honest characters in the book in honour of Wilson Harris, while Gurr is the fictionalised version of a man he met in Berbice in Guyana. Added to these is another noble character, Dr Richmond, who, in history was the medical doctor on the first ship that carried indentured labourers from India to Guyana in 1838.

Dabydeen imposes authority as a story-teller with a very clever narrative design. This book will not be remembered as one of the great epistolaries. The work is not entirely devoted to the suitor’s letters and is not coloured by his character and style. In fact, there are several other narrators whose interventions destroy whatever magic could have been performed by the letters. But Dabydeen seems fully aware of this, as he scrupulously, if not repetitively, inserts several endearments, greetings and addresses to “Dear Sweet Li Jie” in order to sustain the idea of a story told through a series of letters.

Yet, the design is ingenious. Li Jie has a prevailing presence in the novel. She is an inspiration – she represents an aspiration, a goal, a motive for Jia Yun telling the story, and this inspiration is infectious. It spreads over to the stories told by other narratives such as the picaresque adventures of Baoyu the knife thrower. He is illiterate but “writes”, narrates “letters”, stories sent in his imagination to the beautiful Swallow Tail in similar fashion. In a parallel love story to that of Jia Yun and Li Jie, Swallow Tail is Baoyu’s symbol of hope and aspiration. She is not only the motivation for the knife thrower telling his stories, she is, like Li Jie, a humanising influence, and the entire story of the novel is extraordinarily characterised by this.

The cruel landlord Wang Changling’s voracious reading and his ambitions to be a writer have an enlightening, humanising influence upon him, replacing his cruelty with generosity, typified by his kindness to Sweet Li Jie and her mother, his compassion for his feudal servants and even small animals and insects. The charm of the concubine Yin Yin is yet another manifestation of this in her power over the Emperor in the landlord’s version of the Yang Lun Rebellion. Wang Changling’s enlightened transformation ends with one of the most moving moments in the book. Sweet Li Jie is a novel about the humanising of dehumanised human beings.

This, above all, is the meaning of the title of the book, Sweet Li Jie, which almost describes itself. Very simply put, it is a tale driven by the narrator’s devotion to a sweet girl named Li Jie, who is an inspiration for sweetness. But its sweetness as a romantic novel is outdone by the sweetness of Dabydeen’s masterful, seductive, enticing prose; the sweetness of its high entertainment value, and its consistent focus on the triumph of the inherent goodness and charity in the human spirit, despite the deformities in the human form, like Baoyu and Gurr, and the novel’s several tragic circumstances.

During his illustrious and highly decorated career, Dabydeen has given us works of poetry such as the Commonwealth Prize Winner Slave Song, several signature, often anthologised dramatic creole verses on East Indian life in Guyana found in Coolie Odyssey, and the most profound poetic exploration of the trans-Atlantic slave passage in his best poetry – the very interrogating intertextual long poem Turner. This time, in his latest oeuvre, Dabydeen has captivated readers with Sweet Li Jie – asserting an intoxicating descriptive power, a riveting narrative, a masterful control of emotions, a colourful, vivid, memorable dissection of landscape, and a confident linguistic authority characteristic only of the supreme heights of fiction writing. Only a poet could have produced such prose.