(Cont’d from 15 December)

Akima McPherson (AM): Charlotte and Mal, I have enjoyed sharing this space with you the past two weeks. Thank you for obliging me. As we conclude this week, I am eager to learn about your individual experiences of sharing the work there in London. How have your audiences responded?

Mal Woolford (MW): It is important to us that the work has a resonance in Guyana and isn’t some London-centric fantasy. Having an extended conversation with you is very much part of keeping ourselves accountable.

We reached the point last month where we knew we needed to show the work so that we can shape its progress. A quick pop-up show if you like, to see the images larger and rubbing up against each other, really feel how they resonate and what they seem to be communicating. Having a good number of people from all backgrounds come and explore them has been so valuable.

AM: Do you mind sharing some of the insights? Yours or theirs (the audiences’)?

MW: The story of how we came to realise our connection really catches the imagination. Quakers in Britain [https://www.quaker.org.uk/news-and-events/news/quakers-in-britain-marks-first-year-of-work-on-reparations] are corporately researching how they might approach reparations for transatlantic chattel slavery and have a longstanding commitment to racial justice. We’re hoping to exhibit more widely in connection with them and also explore ways to share the work with Heirs of Slavery [https://www.heirsofslavery.org] who are advocating for reparations.

We’re getting feedback that the exhibition was particularly useful in breaking through an invisible barrier of embarrassment and confusion in talking about the subject, and people feel more enabled to start having conversations around the slave trade.

AM: Thanks for sharing those links, Mal. And since you have now visited Guyana you see how that shameful episode of human history continues to define our Guyana spaces and our experiences. So, the fact that many Caribbeans have been saying there needs to be a meaningful address for the exploitations of the past I suppose is even more meaningful to you. … Feel free to respond, Mal but I’d really like to hear from Charlotte. You had said that the tours you each gave of the exhibition were very different and you remarked on the potent way Charlotte spoke of the work. Charlotte, do you mind sharing?

CW: Doing the tours was amazing and fascinating as well. Black people who came had a story. Every black person I spoke to had a story and a curiosity about their name. They knew their name wasn’t from where they were from and they began to openly question.

And I also felt like it was a safe space for white people to have those conversations with me as well and admitted their thoughts and feelings about slavery. It’s such a huge and weighty subject but in that small space with those photos, everybody felt free to talk about it.

I spoke more about how we met, the process of wet plates, test shots and the small pictures of my great-grandmother and her sister, my grandmother and her sister. My mum gave them to me and Mal so he could print them. They became an interesting talking point as well.

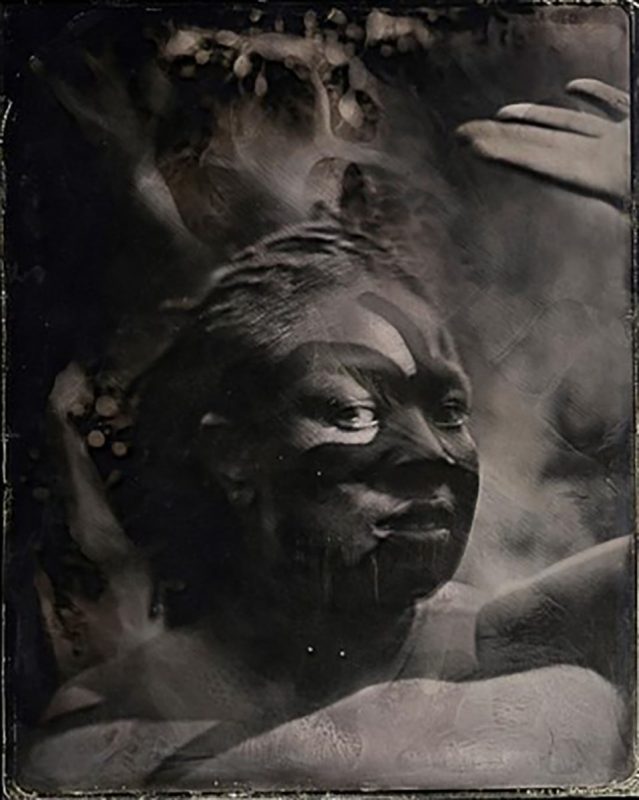

I feel like it all came full circle with our exhibition. Photos that I certainly dismissed came to tell our story and connection the most. The photo with my hand over my face is a perfect example of this. We were completely overwhelmed that day and really tired from looking at all the stuff that we printed from Guyana. We were a bit lost so we decided to look through books to try and see what would spark our interest and there was one book that had a lot of lines and shadows, so we used that as inspiration. The first thing my mother-in-law says when she sees the photo is, “Oh my gosh you look like a warrior that has painted your face, like in ‘Roots’.” One of the last wet plates we took but yet it still speaks of our journey.

AM: What do you anticipate the future has in store for your working together?

MW: We’re hoping to show the work widely and for it to encourage people to engage with the history and each other. We’re already planning a new sequence of images and also looking forward to following where the wet-plate process takes us.

CW: Yes. Playing and exploring. And printing. I’d love to make cyanotypes of our images.

AM: Sounds wonderful. And I hope one day a selection of your work can be shown in Guyana. Maybe, the ‘forces that be’ will see it relevant to support both a show and your making of more work engaging with this marked landscape. And as we close, for me the most important thing about the work and the project is that it opens up space for healing. Best wishes to you both.

The wet-plate collodion process superceded the daguerreotype in the early 1850s. To form an image, a syrupy salted collodion is poured onto glass and then made photosensitive in a bath of silver nitrate. While the surface is still wet, it is exposed in a camera and then developed, washed and fixed. The glass plate carries a negative image which reads as a positive against a dark background creating a physical image known as an ambrotype. (No Relation, Press release)

The work done in Guyana for the project was supported by inputs from young artist and project assistant Rouchelle Stephens; photographer Michael C. Lam; Curator (ag) of the National Gallery of Art, Castellani House, Ohene Koama; and Akima McPherson. The exhibition ran from 17 November to 1 December at the Westminster Quaker Meeting House, London. Viewings by appointment are possible through December.