In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket, the second of three parts, Roger Seymour looks at the uncanny conclusion of the Fourth Test in a series between the West Indies and Australia, Down Under. Part One, ‘A Tale of Tailenders’ was published on 22 December, 2024.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” – Mark Twain

Prologue

Fourth Test, Adelaide Oval, South Australia, 1st February, 1961. The series was tied at 1 – 1. It was the last session of play on the final day. One hour and 50 minutes remained. Chasing a target of 460, the hosts were in dire straits at 207 for nine. Australia’s last batsman, left arm wrist spinner Lindsay Kline ventured to the middle to join allrounder Ken Mackay, seventh in the batting line up. The match was as good as over. The final rites awaited. It was a deja vu moment for Frank Worrell, on his second visit to Australia, his first tour as Captain of the West Indies.

When the West Indies arrived in Australia in mid-October 1960, Test cricket was deep in the doldrums, the result of some of the most dour play that the game had ever witnessed. Of the 11 dullest tests ever contested (measured by run-rate when at least 20 wickets fell), ten had been played in the previous six years. Test cricket seemed destined for obscurity. The former great Australian batsman Don Bradman, then chairman of the Australia Board of Control for International Cricket (whose influence on Australian cricket extended long past his playing days), prior to the start of the series had challenged the two teams to play positive cricket. Over the course of the Five Test series, the two sides led by Richie Benaud and Worrell, respectively, did not disappoint, delivering down-to-the-wire finishes, thus igniting a renewed interest in the game at the highest level.

First Test, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, December, 1960, at Brisbane. Scores: West Indies, 453; G Sobers, 132, F Worrell, 65, J Solomon, 65, F Alexander, 60, W Hall, 50, A Davidson, 5 for 135, and 284, F Worrell, 65, R Kanhai, 54, A Davidson, 6 for 87. Australia, 505; N O’Neill, 181, R B Simpson, 92, C C McDonald, 57, W Hall, 4 for 140, and 232, A Davidson, 80, R Benaud, 52, W Hall, 5 for 63. One of the most thrilling Test matches ever contested, it was the first tie in the history of Test cricket.

Second Test, 30, 31, December, 1960, 2, 3, January, 1961, at Melbourne. Scores: Australia, 348; K Mackay, 74, L Favell, 51, W Hall, 4 for 51, and 70 for three. West Indies, 181; R Kanhai, 84, S Nurse, 70, A Davidson, 6 for 53, and 233, C Hunte, 110, F Alexander, 72. Australia won by seven wickets with a day to spare. A disastrous third day, following the loss of several hours of play to rain on the second, saw the visitors lose 14 wickets and follow on 167 behind. Only four West Indian batsmen (Kanhai, twice) had scores in double figures.

Third Test, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, January, 1961, at Sydney. Scores: West Indies, 339; G Sobers, 168, A Davidson, 5 for 80, R Benaud, 4 for 86, and 326, F Alexander, 102, F Worrell, 82, R Benaud, 4 for 113. Australia, 202; N O’Neill, 71, A Valentine, 4 for 67, L Gibbs, 3 for 46, and 241, N Harvey, 85, N O’Neill, 70, L Gibbs, 5 for 66, A\ Valentine, 4 for 86. West Indies won by 222 runs to level the series.

Prior to the commencement of the Test series, the West Indies had matched forces with the five state sides which competed in Australia’s Sheffield Shield Tournament, the domestic first-class competition, and a few state country XIs in non-first class encounters. In the second match of the tour , they had lost to Western Australia by an innings and 94 runs at Perth, followed by a draw with South Australia at Adelaide in a rain-affected game, before conquering Victoria by an innings and 171 runs, thanks in part to a swashbuckling innings of 252 from Kanhai. An embarrassing defeat was suffered at Sydney, where New South Wales won by an innings and 119 runs, as the visitors failed to pass 200 in either innings. The last day of the Queensland game at Brisbane was washed out with the game delicately poised: the hosts leading by 263 with two wickets in hand. In their only at bat, the visitors had replied to Queensland’s challenging 431, with a respectable total of 357.

The Tied Test was followed by the infliction of innings defeats on a Queensland Country XI and a Northern New South Wales XI, and then another humiliating innings loss to New South Wales during the Christmas season. The Second Test loss, was followed by a five-game win streak, with the Third Test victory sandwiched between two positive results in Tasmania, and defeats of two country XIs.

Fourth Test, at Adelaide. First Day, Friday, 27 January, 1961

The West Indies made no changes to their victorious Third Test team, which read: Conrad Hunte, Cammie Smith, Rohan Kanhai, Garry Sobers, Frank Worrell, Seymour Nurse, F ‘Gerry’ Alexander, Joe Solomon, Lance Gibbs, Wes Hall, Alf Valentine. The Australian made four changes, three due to injuries: Peter Burge replaced Neil Harvey, Des Hoare and Frank Misson came in for Alan Davidson and Ian Meckiff, respectively, and Lindsay Kline was preferred to Johnny Martin. On paper the Australian batting line up was now clearly weaker with an extended tail: Colin McDonald, Les Favell, Norman O’Neill, Bob Simpson, P Burge, Richie Benaud, Ken Mackay, Wally Grout, F Misson, D Hoare, L Kline.

Worrell won the toss and elected to bat on a very hot day. Hoare, on Test debut (on what would be the only match of his career), struck early, trapping Hunte via the LBW route. Kanhai arrived and immediately went on the attack on the easy-paced pitch, sparing no bowler from his fury. At 83, Smith, 28, fell to Benaud, who had been greeted with a massive six by Kanhai. Sobers soon followed, and Worrell arrived to complement Kanhai’s barrage of scoring shots. At lunch, the West Indies had raced to 133 for three, with Kanhai, 76, and Worrell, 15. The torrent of runs continued after lunch much to Benaud’s consternation, as 46 poured from the first five overs, with Worrell’s elegant boundaries matching Kanhai’s plundering of any loose deliveries. Kanhai passed the century mark during this avalanche, and soon afterwards, Worrell hooked Benaud to the fence to bring up the hundred partnership.

The little Maestro eventually edged a delivery from Benaud into the eager hands of Simpson at slip. Kanhai’s masterful innings of 117, which had occupied two and half hours, included 14 boundaries and two sixes, was the highlight of the day. West Indies, 198 for four. Nurse joined his captain, and the flow of runs dipped a bit, as the extreme heat began to take a toll on the West Indies skipper. After tea, a depleted Worrell turned a delivery from Hoare into the safe hands of Misson at short square-leg, ending his textbook perfect innings of 71. 271 for five. Nurse, and his new partner, Solomon, kept the score ticking along. On 49, Nurse fell to an acrobatic catch to Misson, off his own bowling. At the close of play, the West Indies were well placed at 348 for seven, with Alexander, 38, and Gibbs, 3, holding the fort, having added an unbroken 32 to the cause.

Second Day, Saturday, 28 January, 1961

A hot wind blew across the picturesque ground when play resumed the next morning, as Alexander and Gibbs took their partnership past the 50 mark, with the former notching his fourth half century in as many matches in the series. Once Misson clean bowled Gibbs for 18, Hall and Valentine didn’t offer much resistance. Alexander, 63*, had guided the “nine, ten, jack” in the lineup, as had become his rote in the series, whilst adding 105, to the final score of 393. The West Indies innings had lasted 428 minutes. Benaud, five for 96, and Misson, three for 79, were the leading bowlers.

Australia opted to send Flavell as McDonald’s opening partner instead of Simpson, who had opened in the three previous Tests. The strategic move didn’t pan out, as Flavell, (1), fell to a catch to Alexander, off Worrell. O’Neill followed soon afterwards, via the same route, this time off Sobers, to leave Australia in a spot of trouble at 45 for two. McDonald and Simpson consolidated the innings, and between lunch and tea, they hardly played an attacking shot during the 26 overs the West Indies delivered. At the close of play, Australia were 221 for four, with Simpson, 85*, and Benaud (who had opted for the role of night watchman), 1*. McDonald’s dogged knock of 71 had been the bedrock of Australia’s reply, whilst their best batsman on the day, Burge, had his powerful innings of 45, cut short by Sobers, late in the day, when Worrell surprisingly took the second new ball, and shared it with Sobers.

Third Day, Monday, 30, January, 1961, Australia Day

The day began with the two teams taking part in a flag-raising ceremony to commemorate Australia Day. Hall, bowling from the river end, managed to tempt Simpson into nicking the second ball of the day to Alexander, who gleefully accepted the chance. Mackay’s and Benaud’s aggressive approach to Hall and Sobers yielded 48 quick runs, and with the score on 269 for five, Worrell effected a double change, bringing on Gibbs and Valentine.

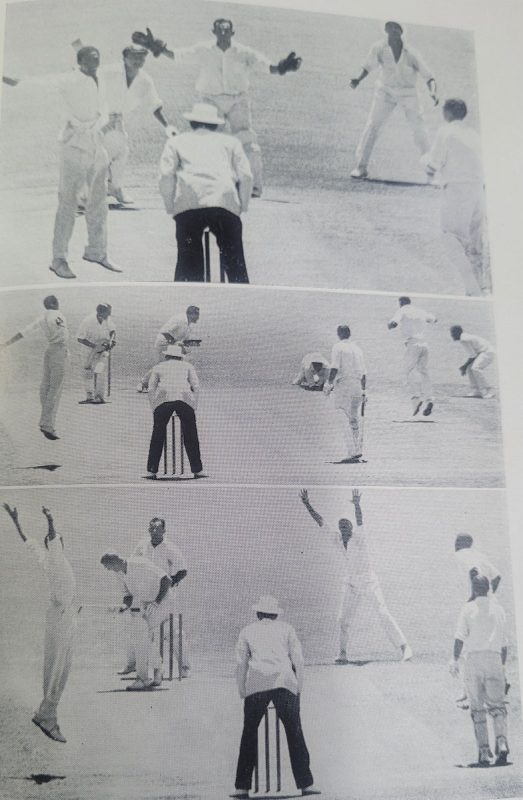

Gibbs trapped Mackay LBW for 29. Grout prodded forward to the next delivery, edged it around the corner, where the omnipresent Sobers readily accepted the catch. Misson arrived, and Gibbs delivered a faster one, which beat the bat and hit the stumps. Hat trick for the lanky off-spinner from British Guiana! It was the first on an Australian ground since Hugh Trumble achieved the feat against England in 1903-04. It was the second hat trick ever performed by a West Indian bowler, Hall having accomplished it against Pakistan.

At 281 for eight, the West Indians must have been relishing thoughts of a lead of 100 runs or thereabouts. A miffed stumping chance just before lunch put heed to that wish, and Australia were 302 for eight at the interval. Hoare held firm while Benaud intelligently accumulated runs, nibbling away at the deficit. It took the return of Sobers to break the critical partnership of 85 runs, which had nullified the threat of a substantial West Indian lead. By the time Benaud holed out to Solomon off Gibbs, his vital innings of 77, spread over two and a half hours, had cut the visitors’ advantage to a mere 27 runs. Gibbs’ figures of 35.6 – 4 – 97 – 5, were the best of the WI bowlers.

The West Indies began their second innings, at quarter past three, and the Barbadian opening pair of Hunte and Smith wasted no time, plundering Hoare, Misson and Benaud for boundaries. Smith’s contribution of 46 to a partnership of 66, in about an hour contained ten fours. Kanhai joined Hunte and immediately picked up where he had left off in the first innings, swotting boundaries off all the bowlers, as he raced past Hunte, who had an hour’s head start. At the close, West Indies were 150 for one, Hunte, 44*, and Kanhai, 59*, a lead of 177.

Fourth Day, Tuesday, 31, January, 1961

Kanhai and Hunte continued in their aggressive frame against the spin attack of Benaud and Kline, with smart running between the wickets, albeit somewhat risky at times. Hunte passed the 50 mark, and the 100 partnership arrived in even time. Benaud opted for the new ball at 202 for one, and Kanhai cover drove Misson to the boundary to move into the 90s, whilst passing 1,000 runs in first-class games in the tour. Another boundary and a few singles, and Kanhai was standing on 99. Facing Misson, he played the ball a few yards away, called and took off. Hunte accelerated, Misson following through, under armed a throw, shattering the stumps. Hunte was run out for 79, when well set for a century. The second wicket partnership of 163 had set a new record for West Indies/Australia Test matches.

Kanhai, despite being crowded by Benaud, managed to late cut Hoare for a boundary, to complete his second century of the match. He joined the exclusive club of West Indian batsmen to have attained the feat; George Headley (twice), Everton Weekes, Clyde Walcott (twice), and Garry Sobers. Perhaps upset at Hunte’s needless run out, Kanhai got stuck at 103 for almost three-quarters of an hour. After lunch, he was LBW to Benaud for 115, a masterful innings. Kanhai’s departure led to a sudden momentum shift as the visitors slumped from 263 for two, to 275 for five; Sobers was needlessly run out by Misson in similar fashion to Hunte and Nurse edged Benaud to Simpson at slip.

Alexander joined Worrell, and once again, provided the impetus to swing the match in favour of the West Indies. The Vice-Captain and Captain, using their skill and experience, led the revival and the chase for quick runs with a flurry of boundaries. The total reached 350 at half past three, as the pair pressed on, adding 50 in 32 minutes. By tea, the lead was 387. It was too early for the declaration, too much time remained, and there were not enough runs. When the West Indies continued their innings, the pair swotted boundaries, raising the 100 partnership in less than even time. Worrell was dismissed for 53, falling to a difficult catch at deep backward square-leg. It was his second 50 of the match and fifth of the series. Solomon and Alexander swung lustily, piling on the runs, as the clock ticked away. When Worrell declared at quarter past five, the West Indies were 432 for six, with Alexander, 87*, and Solomon, 16*.

Australia’s target was 460 in six and a half hours. A few voices in the media felt that Worrell had exercised too much caution and had left it too late. By the close, the doubts had been removed. Australia had been reduced to 31 for three, and the discussion centred around whether Australia could survive the last day on the dead pitch. Favell, after hooking Hall to the boundary, edged a catch to Alexander, McDonald was run out by Kanhai going for a needless run, and then off the penultimate ball of the day, Simpson emulated Favell’s dismissal.

Fifth Day, Wednesday, 1 February, 1961

Australia’s goal was simply to bat through the day. O’Neill and Burge applied themselves to the task, as Worrell opted not to apply any pressure by setting an attacking field, despite having runs to play with.

The Australian score passed the century, as the two batsmen ambled along, apparently in full control. Valentine returned from the river end, and lured Burge into the cut shot, only for Alexander to claim another catch. The lunch interval passed, with Benaud and O’Neill coasting along, their eyes set on the tea break. Just after two o’clock, O’Neill’s concentration waned and he hit a return catch to Sobers. As long as O’Neill remained, there was a glimmer of hope for Australia. Only Mackay of the regulars was left, and there were still 210 minutes of play. Mackay was nearly caught at leg slip off the first ball he received from Gibbs, who had been brought back to torment the left-hand batsman.

Sobers soon repeated the O’Neill trick with Benaud, and Australia were on the ropes at 144 for six. Wally Grout arrived and got stuck in. Worrell, getting desperate, went through the entire rotation, even tossing the ball to Solomon for three overs, as he tried everything to separate the Queensland pair Finally, Worrell trapped the pesky wicketkeeper LBW, for 42, having occupied the crease for an invaluable hour and a quarter. At tea, Australia were 203 for seven. After Worrell had Misson caught at leg slip by Solomon, he clean bowled Hoare. 207 for nine. Lindsay Kline ventured down the pavilion steps to join Ken ‘Slasher’ Mackay.

Deja vu moment

Worrell had been here before. Nine years ago, Fourth Test at Melbourne, last pair, 38 runs to get. And they had lost, Worrell having delivered the fateful delivery to concede the winning run. Valentine had also been on the field then. Worrell could envision Manager Gerry Gomez and Sonny Ramadhin, two other members of that disappointing 1951/52 Tour exchanging wordless glances in the dressing room.

The strategy was obvious, focus on Kline. Mackay was no rabbit. In the state match against Queensland, Mackay, the state captain, batting at three, had hammered an out-of-character innings of 173, and in the Second Test, his 74 was the top score in Australia’s first innings. One hour and 50 minutes remained, plenty of time. There was only one possible result.

Two minutes after Kline’s arrival, Sobers, fielding four yards from the bat at silly point, appealed for a catch off Mackay. Worrell was again the bowler. Sobers, confident that he had taken a clean catch, along with the rest of the jubilant close fielders started to canter off the ground. Mackay stood his ground. Australian Umpire Egar promptly rejected the appeal. Mackay was 17 not out. The match continued.

Worrell tried every bowler at least twice. The new ball was taken at five o’clock and Hall could do nothing with it on the lifeless pitch, as both batsmen played him comfortably. Worrell reverted to the spinners. Nine fielders surrounded Kline as Gibbs and Valentine whistled through overs in two minutes (bear in mind these were eight-ball overs). Now and then the ball popped in the air, but it always landed safely.

The pair added 66 runs, as the West Indians grew desperate. One minute to six, Worrell tossed the ball to his willing workhorse, Hall. Despite pounding everything in, the ball didn’t lift on the lifeless pitch. Last ball. Mackay, knowing that he couldn’t be ruled LBW took it on the body. A few West Indians helped the badly bruised Mackay off the field. He had survived for 233 minutes whilst scoring 62. Kline’s resolute bat had contributed 15 to the unbroken 67-run partnership. The match was over. Australia had escaped with a draw against all odds.

Aftermath

Sobers’ catch was one of those incidents that will be discussed until the end of time. English sport writers covering the tour were convinced that the West Indians had been stiffed. All manner of deflections were proffered including: Worrell had left his declaration too late, and if Gibbs’ spin finger wasn’t sore, the match might have been won. One key point never brought up in this discussion was that no one – in any part of the cricketing world – ever questioned Sobers’ integrity or sportsmanship. Never.

It was not the only controversial incident of consequence in the series. There was the Grout incident – he cut the ball on to his stumps and a bail fell, later confirmed by film – as the deciding Fifth Test wound down to another close finish. Alexander appealed and Umpire Egar stated that he was uncertain how the bail came off, and gave Grout the benefit of the doubt.

A few lucky bounces and the West Indies might have won this series 3 – 1.

Notes

Fifth Test, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, February, at Melbourne. Scores: West Indies, 292; G Sobers, 64, F Misson, 4 for 58, and 321, F Alexander, 73, C Hunte, 52, A Davidson, 5 for 84. Australia, 356; C C McDonald, 91, R Simpson, 75, P Burge, 68, G Sobers 5 for 120 and 258 for eight, R Simpson, 92, P Burge, 53. Australia won by two wickets.

O’Neill’s century in the First Test was the only one scored by an Australian, while the West Indians compiled six.

Wicketkeeper Franz ‘Gerry’ Alexander, the former West Indies Captain, recorded the unique feat of scoring a half-century in every Test, and led the batting averages with 484 runs at 60.50.