Budget 2025, presented on 17 January 2025, is the final budget of the Twelfth Parliament. It is the fifth presented by Dr Ashni Singh, Minister with responsibility for Finance, and the sixth of this Government before elections in the last quarter of the year. The Minister’s hours-long speech was needlessly peppered with political attacks on the APNU+AFC Coalition and PNC-R and presages a stormy debate unbecoming of the occasion.

Breaking from the conventional practice of limiting commitments during an election year, the Budget presents an ambitious agenda extending beyond Parliament’s anticipated prorogation. This comes against a backdrop of deeply troubling parliamentary dysfunction: committees are either non-functional or inefficient, Members’ Days have virtually disappeared, and the Administration treats Parliament as a mere convenience, summoning it only when expedient. The government’s position that its mandate continues until a new government forms rings hollow, given its systematic undermining of parliamentary oversight.

The Speech’s timing is significant, especially coming days before Donald Trump’s return to the White House. His First-Day Executive Orders have already demonstrated that his promises must be taken seriously. His “Drill Baby Drill” policy and potential engagement with Venezuela could fundamentally alter the regional energy landscape. More ominously, his threat of sweeping tariffs can upend the global economy, from which few countries will escape.

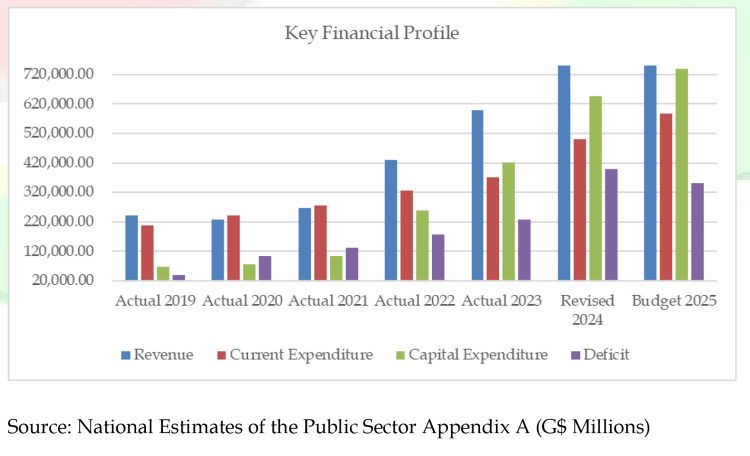

Even a cursory comparison of the Ali Administration’s approach to budgeting and spending and that of its predecessor shows marked differences. The chart below shows four key variables from 2019 (pre-oil) to the present: Current Revenue, Current Expenditure, Capital Expenditure, and Deficit – the latter financed by loans – while any surpluses could augment the Consolidated Fund. We chose 2019 as our benchmark as the last full year before the change of Administration.

The numbers are striking: Revenue increased 326% (from $240,585M to $1,024,459M); Current Expenditure 183% ($207,683M to $587,951M); Capital Expenditure 1013% ($66,262M to $737,680M); and the Deficit 774% ($40,028M to $349,981M).

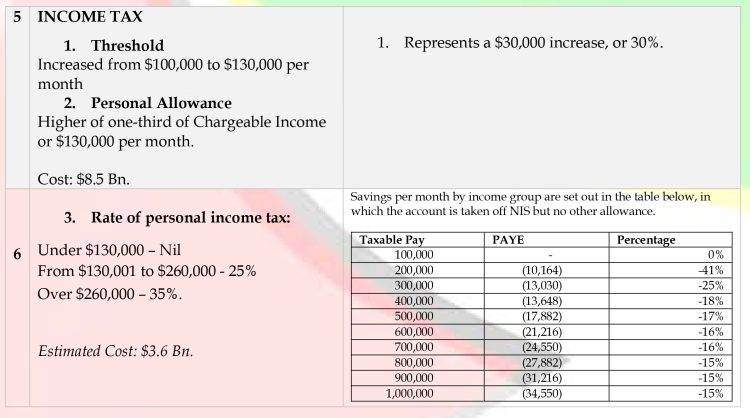

We note with serious professional concern the proliferation of discretionary funds that challenge basic principles of public financial accountability. One such programme, inaptly described as “Cost of Living measures”, has grown to $9 Bn., with similar measures multiplying across ministries. These discretionary allocations make audit trails practically impossible: verification of beneficiaries, disbursement criteria, and value-for-money assessments are severely compromised.

While the Speech repeatedly references “One Guyana,” it notably omits any discussion of the key Silica City project, raising questions about unaccounted funding sources. The Minister attempted to offer something to everyone, even repeating effectively shelved measures while introducing tax provisions that burden the Revenue Authority and create opportunities for tax planners. Remarkably, two days after the presentation, he issued an additional concession disguised as clarification – a first in Ram & McRae’s 35 years of Budget Focus.

Ram & McRae’s Comments

- The dramatic slowdown in overall GDP growth from 43.6% to 10.6% warrants attention, though the strong non-oil growth of 13.8% – not unrelated to the petroleum sector – is encouraging.

- Crossing the $1 trillion revenue mark is historic, but it will require substantial increases in current and capital expenditures.

- The proliferation of subsidies, grants and allowances addresses symptoms rather than causes of high living costs. Structural economic reforms are needed rather than palliative measures.

- Tax concessions and social measures, while providing immediate relief, create significant long-term fiscal commitments that must be sustained beyond oil revenues. It is about eight years since the last Tax Reform exercise. That does not seem to be on the radar.

Who Gets What in 2025?

Introduction

The priorities outlined in the Budget Speech derive from a complex network of Budget Agencies, Constitutional Bodies, Regions, and various subventions and subsidies. There are some expenditures that do not require approval by the National Assembly: they are referred to as direct charges and include the Courts and the payment of the public debt. In dollar terms, these are modest. Most of the expenditure require parliamentary approval – a crucial mechanism for spending public funds.

The chart above shows the actual expenditure, exclusive of the public debt, from 2015 to 2023, the latest estimate for 2024, and the budget for 2025. A few things are immediately obvious. The first is how total expenditure has ballooned, particularly with the advent of oil in 2020. Total Expenditure has jumped from $171,817 Mn in 2015 to $317,710 Mn. in 2020 and to a budgeted figure of $1,325,633 Mn. in 2025. In other words, expenditure increased by 85% under the APNU+AFC Coalition, and it is expected that expenditure will rise by 317% under the current administration.

The second point of note is that under the Coalition, Current Expenditures significantly exceeded Capital Expenditures, while under the current PPP/C Administration, Capital expenditures increased rapidly from 2021 to surpass Current Expenditures in 2023. Capital spending from 2015 to 2020 represented 30% of total expenditures, and for the years 2021 to 2025, that percentage has risen to 48%.

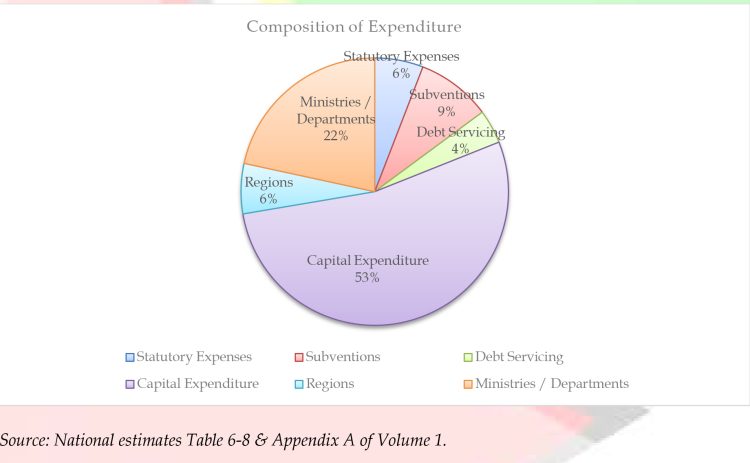

In addition to Capital Expenditure, there are five heads of expenditure: Ministries/Departments, subsidies, Regions’ Statutory Expenses, and Debt Servicing. Their share of the total expenditure is shown in the pie chart below.

Statutory Expenses and Subventions

Capital Expenditure represents expenditure on capital projects financed out of the Consolidated Fund and includes such expenditure by statutory bodies and Regions. The Chart confirms the allocation between Capital and Current Expenditure.

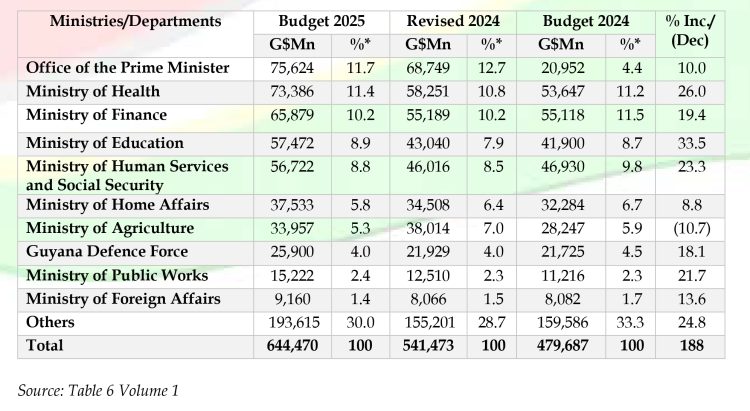

Focus now considers the proposed spenders of funds in 2025, comparing the amounts budgeted to Budget 2024 and Revised (Budget) 2024 taking account of supplementary appropriations approved by Parliament. There were two such appropriations for 2024.

Current Expenditure Analysis

Current expenditure, totalling $644,470 million, reveals both traditional patterns and emerging priorities in government operations.

Top Five Current Budget Recipients

Office of the Prime Minister

This Office has moved up from #8 last year by Budget to top of the list of spenders, from a Budget of $20,952 Mn to $75.624. Mn. The Office of the Prime Minister emerges as the largest recipient of current expenditure, commanding $75,624 million (11.7%) of the allocation. Two Programmes – Disaster Preparedness and Power Generation account for $41,271 Mn and $25,549 Mn or 55% and 34%. Under Power Generation, $25,541 Mn is shown as a subsidy and contribution to local organisations, principally GPL ($16,000 Mn) and Linmine ($4,755Mn).

One hundred and twenty-seven of the 142 employees are contracted employees.

The substantial allocation for the strangely named Disaster Preparedness is the amount allocated for the $100,000 Cash Grant in 2025. A supplementary appropriation of $41,225 Mn was allocated in 2024. The Minister, in his Budget Speech, reported that 300,000 cheques were printed, but only 90,000 were distributed.

Ram & McRae’s Comment

The disparity between cheques prepared and distributed requires explanation.

The broader question is why this project was placed under the Office of the Prime Minister when the Ministry of Finance executes the programme and why it falls under the broad rubric Disaster Preparedness. There appears to have been little preparedness for the programme, which continues to resonate with confusion.

Ministry of Health

The Minister announced that key projects in the sector include commissioning the Paediatric and Maternity Hospital at Ogle, six regional hospitals, and upgrading Lethem Regional Hospital. It is unclear how these could be completed and put into operation with a rather modest increase in the number of employees from 4,273 to 4,416. Employment costs are projected to increase from $14,381 Mn to $16,252 Mn, an increase of 13%.

It should be noted that the Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation is an independent institution, although the Ministry exercises considerable oversight over it. Under the allocation for this Ministry, GHPC will receive a subsidy (subvention) of $20,003 Mn, up from a revised $18,826 Mn in 2024.

The Minister did not indicate whether the new health facilities will be controlled centrally or otherwise.

Healthcare access is a human right, and the government deserves credit in this area. Yet, private healthcare is proliferating and benefits from extremely attractive incentives. We believe that there is considerable scope for planning and coordination which must include population data and technology.

Ministry of Finance

The Ministry of Finance’s allocation of $65,879 million (10.2% of total current expenditure), an increase of 19.4% over 2024. The Ministry has two programmes – Policy and Administration ($48,494 million) and Public Financial Management Services ($17,385 million). The Ministry supports two major entities through subventions – the GRA ($10,814 Mn) and the NIS $10 Bn to finance the program announced to assist persons whose contributions range from 500 – 749. Of the 251 employees, 144 are contracted.

Ministry of Education

Education is one of the most high-profile ministries in the Administration. Three of its significant programmes are primary ($16,664 million), secondary ($13,366 million), and post-secondary education ($15,527 million). Of the post-secondary allocation, $11,706 Mn is allocated for the Turkeyen Campus and $1,328 Mn for the Berbice Campus.

The Estimates show that there are 3,949 (2024 – 213) staff, of which Senior Technical accounts for 1,200. It also lists 746 staff as contracted. It is unclear whether there are any contracted employees among the Senior Technical staff.

The employment cost Budget is projected to increase by 26.7%, well above the salary increases agreed with the Guyana Teachers Union or justified by the 5.7% increase in staffing.

Human Services and Social Security

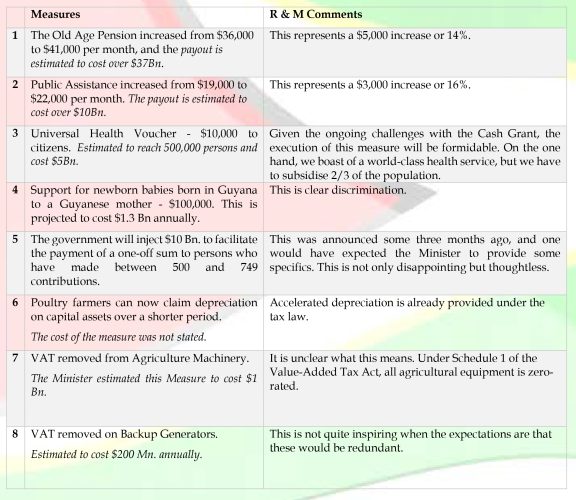

The Ministry of Human Services and Social Security’s allocation of $56,722 million represents an increase of 23% over the prior year. Of this, Social Services account for $55,194 Mn, with Old Age Pensions and Social Assistance accounting for an impressive 92% ($52,931 million) of its budget.

The Minister announced that the Old Age Pension will be increased from $36,000 to $41,000 per month and Public Assistance from $19,000 to $22,000, respectively, an increase of 13.9% and 15.8%.

Over the years, these programmes have drawn inquiries and adverse comments. Helpfully, the Minister volunteered the number of recipients and the rates. Ram & McRae’s computation suggests that about $5,000 Mn overstates the vote.

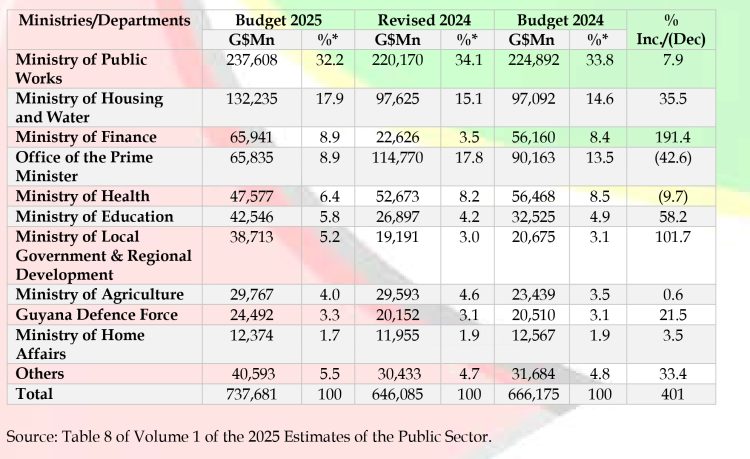

Capital Expenditure

Focus 2025 looks at Capital Expenditure from two angles – my spending agency and by sector.

The details of Capital Expenditure are set out on pages 483 to 546 of Volume 1. Most of these refer to Project Profiles which are contained in Volume 3. Unfortunately, the Profile descriptions are extremely inadequate and are sometimes merely circular.

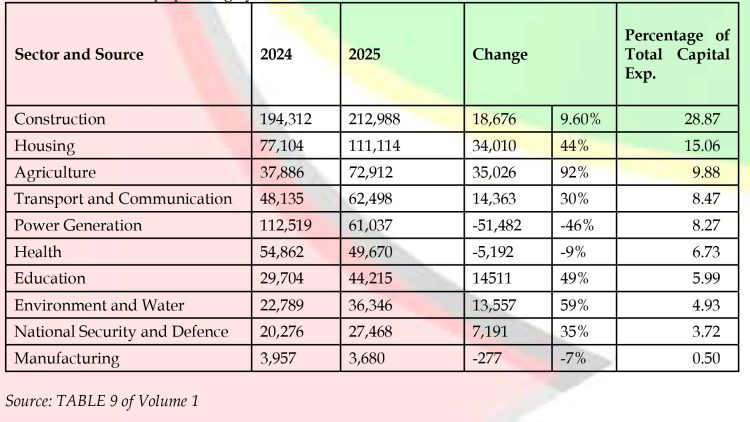

The capital expenditure program, totaling $737,681 million, reveals the government’s spending priorities while highlighting implementation challenges. Construction maintains its dominant position, commanding $212.9 billion (28.87%) of capital spending, though with a modest 9.6% growth from 2024. The housing sector shows remarkable expansion, rising 44% to $111.1 billion (15.06%), while agriculture receives a dramatic 92% boost to $72.9 billion (9.88%). The power generation sector’s 46% reduction to $61 billion (8.27%) primarily reflects the progression of the Gas to Power project toward completion rather than reduced priority.

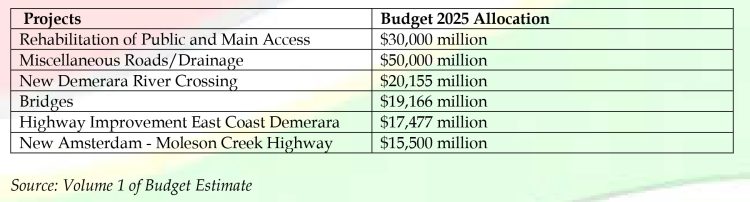

Ministry of Public Works

The Ministry of Public Works remains the largest recipient of the budget, maintaining its position with G$237.6 billion (32.2% of allocation) in 2025. It shows a moderate increase of 7.9% from 2024, suggesting continued prioritisation of infrastructure development. Here is a list of the major projects listed in Volume 1.

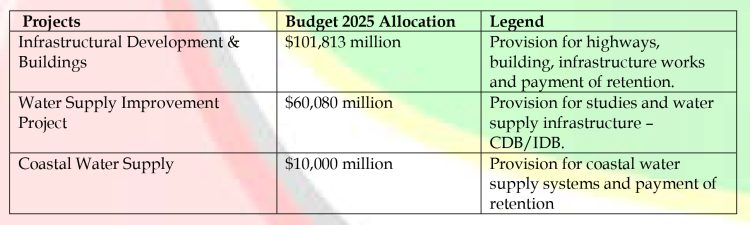

Housing and Water

This Ministry receives the second-largest allocation and a significant increase of 35.5%, rising to G$132.2 billion in 2025.

A notable feature of the 2025 capital budget is the expanded role of the Ministry of Housing and Water, which received $132,235 million (17.9% of the capital budget). This Ministry is allocated $101,814 million for highways and buildings (sic). While potentially expediting development, this dramatic expansion of scope raises important questions about institutional coordination and capacity. What is particularly concerning is the lack of details regarding the expenditure of $101,813 Mn.! This must cross some line regarding transparency and accountability.

Ministry of Finance

This Ministry shows the most dramatic increase of 191.4%, jumping to G$65.9 billion in 2025 from G$22.6 billion in the 2024 revised budget. This substantial increase suggests new financial initiatives or programs being implemented.

Volume 3 describes the project as including the following but without further details. Land Titling; Information & Communication Technology access and E-Services for the hinterland, Poor and remote Communities; Sustainable Land Management and Development; etc. This level of amorphous ambiguity governing an expenditure of $57,401 Mn is not what any taxpayer would expect of the most important financial entity in the public sector.

The Minister reported that in 2024, 15 villages were demarcated and 10 were issued with Certificates of Title.

Office of the Prime Minister

Interestingly, the Office of the Prime Minister shows the largest decrease (-42.6%), dropping from G$114.8 billion in revised 2024 to G$65.8 billion in 2025. The major projects and allocations are the National Data Management Authority ($9.9 billion) and the Gas to Power project ($51.1 billion). The capital budget for the GtP project has added the construction of a control centre to the 2024 list.

Ministry of Health

The Ministry of Health’s budget decreased by 9.7% to G$47.6 billion in 2025. Its major projects and allocations are the Health Sector Improvement Programme ($28 billion), the Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation ($2.9 billion), and the Ministry of Health Buildings ($6 billion).

The Project Profile for the Health Sector Improvement Programme is identical to what was stated in 2024. In addition, the details given by the Minister do not accord with what is outlined in the Project Profile.

Spending by sector

Here is a list of the top spending by sector

Financing

Grants account for $6.134 billion of the financing (XXX) with loans accounting for the balance. The CDB accounts for 78.4% of Grants.

From zero in 2024, the USA tops the list of country lenders in 2025 at $39.1 billion followed by China at $31.8 billion and Sweden at $17 billion.

Other comments

- The widespread media reports of inadequate project planning, problematic contract awards, poor supervision, and substandard quality demand honest and frank attention from authorities.

- Implementation capacity remains a primary concern, with both government agencies and contractors often unqualified for contracts awarded to them.

- Project management capabilities require significant strengthening across implementing agencies.

- The Budget remains primarily a spending authorization tool rather than a strict execution framework.

- Despite the obviously poor and costly management of construction projects, the Government continues to dither on the Engineers Act.

- The current allocation of subsidies and subventions to social organizations lacks transparent criteria. Organizations like the Dharm Shala, Good Samaritan Home, and Sadar Anjuman receive funding that is disproportionately low compared to their vital contributions in supporting vulnerable populations, warranting a thorough review of their allocations.

- Though $218.99 million is allocated to the Constitution Reform Commission, achieving meaningful progress may be difficult in an election year.

- While $87 million is allocated to the Farm Commission, it is uncertain how much meaningful progress can be achieved during an election year, given competing national priorities.

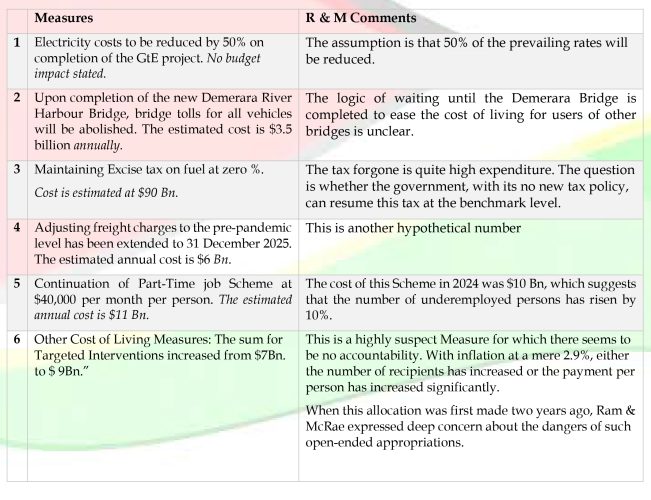

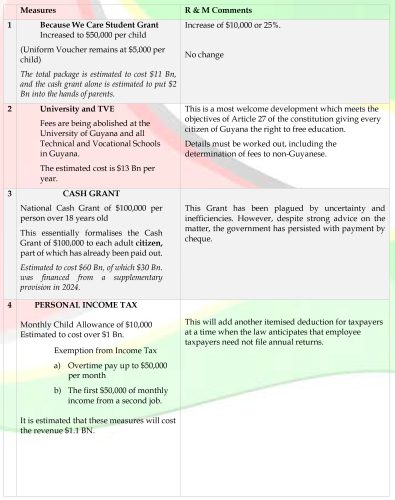

2025 Budget Measures

In this section, we address the measures announced by the Minister and offer our comments on them. The Measures are contained in Part 6 of the Speech. The Budget and the Estimates will be debated over the next two weeks after which they will be voted on and approved.

Measures to ease the cost of living

Measures in Supporting the Vulnerable

Measures for Increasing Disposable Income

Ram & McRae comments:

- The changes in the threshold and the tax rates will result in savings across the population of income taxpayers beginning with those earning $130,000 per month.

- The Estimates offer both projected actual and hypothetical costs totalling $90 Bn. In our comments on Budget 2024, we noted that several forms of grants, most of which are paid in cash, require considerable administration and personnel. Inevitably in such cases, there will be significant leakages beyond the capacity of the Audit Office.

- Itemised deductions are gradually returning to the personal income tax system and carry high administrative costs. The GRA must decide whether and what proof it will require to validate claims of the parent-child relationship.

Commentary and Analysis

The purpose of this section is to draw to the attention of policy makers the issues of interest faced by the country, whether arising out of the Budget presentation or otherwise. Where we consider certain matters of special importance, we may even repeat them, as we have done in the past with Corruption, the National Insurance Scheme and the state of our democracy.

Harnessing the AI Storm: Opportunities for Guyana in Industry, Commerce, and Public Services

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has risen astonishingly, transforming industries, governance, and everyday life. Its pioneers have already been awarded global honours, including the Nobel Prize, for revolutionizing how humans interact with technology. This global storm of innovation underscores AI’s duality: immense opportunities for growth and modernization alongside significant challenges that demand thoughtful navigation. For Guyana, an emerging economy, AI promises to transform industry, commerce, public services, and daily life while addressing systemic inefficiencies.

AI’s Promise for Guyana

AI’s transformative potential spans numerous sectors. In governance, AI-driven tools can streamline processes and enhance transparency. For example, systems capable of managing traffic in Georgetown could reduce congestion, saving countless hours. Similarly, in public health, diagnostic tools and telemedicine could bridge gaps between rural and urban areas, providing life-saving services to underserved communities. However, Guyana must approach this revolution strategically to harness these benefits responsibly.

Industry and Commerce

AI can play a pivotal role in revitalizing Guyana’s industries. In the oil and gas sector, AI tools can optimize exploration, monitor environmental impacts, and predict market trends, ensuring sustainability alongside profitability. The manufacturing sector could benefit from automation technologies, reducing costs and increasing productivity. In commerce, AI-powered analytics can help businesses better understand consumer behavior, enabling more effective marketing strategies and customer engagement.

The banking and finance sectors also stand to benefit significantly. AI can enhance fraud detection, improve credit risk assessments, and automate customer service through chatbots. By leveraging AI-driven predictive analytics, financial institutions can make more informed decisions, fostering economic stability. Guyana’s National Insurance Scheme (NIS) could use AI to streamline claims processing, detect fraud, reduce errors, and improve overall service delivery, ensuring greater efficiency and reliability.

Education and Health Delivery

In education, AI can transform learning by providing personalized instruction and adaptive assessments. Schools in rural areas could use AI-powered tools to overcome teacher shortages and deliver high-quality education to all students. AI-driven platforms can also enhance vocational training, equipping Guyana’s workforce with the skills needed for a digital economy.

The healthcare sector could benefit immensely from AI-driven diagnostic tools, telemedicine platforms, and predictive analytics. These technologies can improve early disease detection, optimize resource allocation, and enhance patient outcomes. AI-powered logistics systems can ensure the timely distribution of medical supplies to remote areas, addressing disparities in healthcare access and improving overall efficiency.

Job Displacement and the Need for Reskilling

Despite its immense potential, AI will inevitably lead to job displacement in certain sectors. The call exchange business, blue-collar roles, and even para-legal positions are particularly vulnerable to automation. For example, AI-powered customer service chatbots and virtual assistants are already replacing human operators in call centers globally. In manufacturing, robotics and automation technologies can perform repetitive tasks more efficiently than human workers, reducing demand for manual labor. Even within the legal sector, AI tools capable of conducting legal research and drafting documents are transforming traditional para-legal roles.

To address this, Guyana must invest in reskilling and upskilling its workforce. Educational programs should focus on equipping workers with the skills necessary to transition into roles that complement AI technologies, such as data analysis, AI maintenance, and creative problem-solving. This proactive approach will ensure that the country’s workforce remains competitive in an increasingly digital economy.

Modernizing Public Services

AI could also be instrumental in modernizing the delivery of social services. Automating administrative tasks within the National Insurance Scheme and other public welfare systems could significantly reduce inefficiencies and improve accessibility for vulnerable populations. Public transportation systems could be enhanced with AI-driven route optimization, reducing fuel consumption and improving reliability. These applications would support a more inclusive and equitable distribution of resources, fostering public trust in governance.

Ethical Integration and Collaboration

The adoption of AI requires robust ethical frameworks to prevent misuse and ensure equity. Drawing lessons from international guidelines, Guyana can develop policies that reflect its unique cultural and social context. Regional collaboration through CARICOM can amplify these efforts, positioning the Caribbean as a model for responsible AI adoption. Such frameworks should prioritize fairness, transparency, and accountability, ensuring that AI serves all citizens equitably.

Guyana’s approach to AI must also involve partnerships with international institutions, private enterprises, and academic institutions. Collaborating with technology leaders and research entities can accelerate the country’s progress while maintaining a focus on national priorities and values.

Conclusion: Shaping Guyana’s Future

As Guyana embraces the AI revolution, it must prioritize strategic planning and ethical governance. By focusing on industry, commerce, education, healthcare, and public administration, the country can unlock AI’s transformative potential while safeguarding against its risks. This journey is not just about technology; it is about shaping a future rooted in equity, innovation, and sustainability.

The challenge is significant, but so is the opportunity. With thoughtful implementation and collaboration, Guyana can harness the AI storm to build a resilient, prosperous, and just society. The time to act is now.

Constitutional Duty and Closing Window: Why Guyana Must Act Now on the 2016 PSA

A statement by John Hess a day ago suggests the extent to which Guyana’s political establishment has betrayed its constitutional obligations through the 2016 Production Sharing Agreement with ExxonMobil. The fundamental issue is not about what share of our patrimony we receive – the government’s “half a loaf” narrative – but rather that the entire resource belongs to the Guyanese people under both international law and our Constitution. Despite widespread public recognition of this basic truth, both major parties appear to be offering private assurances to oil companies while abandoning their duty to protect national sovereignty.

The evidence of this extensive betrayal is stark. Not a single cost audit completed. Ring-fencing provisions rejected. The OECD minimum tax framework unsigned. Relinquishment provisions unlawfully ignored. No Commission of Inquiry established. While the government champions the supposed benefits of stability and warns of investor flight, Hess Corporation’s CEO candidly reveals what the oil companies already suspect – both ruling party and opposition have privately committed to maintain this unconstitutional arrangement.

The companies’ suppression of true reserve figures reveals the cynicism of their position. If reserves indeed exceed 11 billion barrels, a comprehensive analysis of production rates – from the initial 74,000 barrels per day in 2020 through current levels and projected increases – shows the resource would be depleted between 2044 and 2046, depending on whether peak production reaches the suggested levels “well above” 1.3 million barrels per day. This accelerated depletion timeline narrows the practical window for renegotiation. While the Agreement’s duration is tied to active production licenses, the rapid extraction rate means Guyana must act decisively to protect its interests before its bargaining position erodes with declining reserves.

The current Agreement’s terms – a 2% royalty rate among the world’s lowest, absence of ring-fencing provisions, and the extraordinary requirement that Guyana pay ExxonMobil’s taxes – reflect more than just unequal bargaining power. They represent a wholesale surrender of constitutional authority, with the political establishment have now marketing these disadvantageous terms as evidence of stability while systematically avoiding any measure that might restore proper sovereign control.

The “sanctity of contract” and investment flight arguments deployed by political leaders have collapsed under scrutiny. These are mere smokescreens to obscure the fundamental constitutional violation. John Hess’s unusually candid comments about “very low” political risk expose the truth – the companies face no real threat from a political establishment that has put the interests of the international oil companies over their sworn duty under our Constitution.

The path forward requires recognising this crisis for what it is – not a question of better terms but of constitutional sovereignty. Pursuing renegotiation through Article 31.2 is not only about securing a better share of what is already ours by right. It is about reclaiming the constitutional authority that no government had the right to surrender for generations.

As we analyse Budget 2025, the stark reality is that Guyana stands at a critical juncture. The constitutional case for renegotiation is clear. The economic imperative is undeniable. The window for meaningful action is narrowing with each passing month of accelerated extraction. The government’s continued focus on marginal benefits and local content achievements cannot obscure the fundamental necessity of addressing the constitutional and fiscal framework governing our primary national resource. Our professional assessment, based on both constitutional principles and economic realities, is that renegotiation of the 2016 PSA represents not just an option but an urgent national imperative.

Budget 2025: NIS Allocation Overlooks Fundamental Reform Requirements

The 2025 budget presentation includes a $10 billion allocation to the National Insurance Scheme to provide grants for persons with 500-749 contributions. This proposal, which follows the President’s October 2024 announcement, appears to overlook that the NIS Act already contains provisions for such grants. The measure therefore creates a parallel system while leaving fundamental structural issues unaddressed.

The Scheme’s evolution reflects a series of missed opportunities for structural reform. The initial funding framework established under the Burnham administration was followed by administrative decisions that resulted in an underperformance of the Scheme in its earlier years. Some of the problems were addressed but not sufficiently resolved under President Cheddi Jagan. The NIS however was treated as the personal fiefdom of a powerful and influential Chairman Roger Luncheon. Progress was slow and then came the substantial losses following the collapse of CLICO investment. While the Coalition government implemented certain remedial measures, including addressing the CLICO losses through debentures, systematic reform remained elusive.

The current administration’s response has been driven primarily in response to public representations and formal complaints from affected pensioners. The Minister of Finance’s reference to the ninth actuarial report in the context of his 2025 seems a bit self-serving particularly given the extended delay in addressing the recommendations of the 2021 Actuarial Review Report. The failure to implement those recommendations threatened the viability of the Scheme until the providential advent of oil.

The hash approach adopted by the NIS was brought to the fore by the precedent-setting case involving non-compliance by employers causing the denial of contribution benefits to employees. That case was hailed as a landmark victory for the employee and many others facing similar situations. The subsequent administrative response by the Scheme and the government to this judicial determination raises questions about the Scheme’s governance framework and the attitude of the government undermines both the Scheme’s and the Government’s credibility and commitment to their social security mandate.

Recent financial indicators in the NIS show positive momentum. Income increased by 16.5% from 2021 to 2022, the deficit decreased from $3.9 billion to $468 million, and reserves grew by 45.2% to reach $43.3 billion. This improvement has continued into 2023 and 2024. This financial improvement, combined with the government’s enhanced revenue base from various sectors including oil proceeds, provides an unprecedented opportunity for implementing comprehensive reforms.

A significant ongoing challenge stems from the Scheme’s demonstrable unwillingness to pursue outstanding contributions from both private and public sector employers, including those no longer operational. This deliberate forbearance, particularly evident in cases involving state entities, reflects a systemic failure of governance and accountability that directly impacts beneficiary entitlements. The absence of systematic enforcement mechanisms has created a culture of non-compliance that undermines the Scheme’s long-term sustainability.

The required comprehensive reform framework encompasses interconnected legislative, administrative, and governance measures. This includes mandatory timelines for actuarial recommendation implementation, modernization of claims processing systems, and enhancement of board oversight. Critical to this reform is the government’s obligation to ensure appointed directors possess the requisite expertise and competence to discharge their fiduciary responsibilities effectively. The current practice of board appointments requires thorough review to ensure alignment with the Scheme’s technical and governance requirements. The framework would establish clear accountability for contribution collection and create standardized procedures for claims adjudication. Particular attention must be paid to updating the technological infrastructure to enable more efficient record-keeping and claims processing.

Implementation of these reforms requires not only financial resources but also political will and administrative commitment. The estimated cost of these integrated reforms, at approximately $5 billion, represents half of the proposed allocation. Given the government’s current fiscal capacity, implementation of these structural changes appears both feasible and necessary. The opportunity exists to address systemic issues and establish a sustainable framework that would better serve the interests of contributors and beneficiaries than the implementation of parallel benefit systems.

The reform agenda must also address the fundamental relationship between the Scheme and its stakeholders. This includes establishing clear service standards, implementing transparent reporting mechanisms, and creating effective channels for stakeholder input in policy decisions. Only through such comprehensive reform can the NIS fulfill its mandate as a reliable and efficient social security system for all Guyanese workers.

Constitutional Reform in Guyana: The Path to Democratic Maturity

“This is the moment for transformative constitutional reform,” declared Attorney General Anil Nandlall during the Constitutional Reform Commission bill debate. His words carry a weight of history – both of promise and disappointment – that every Guyanese understands. Our constitutional journey has been marked in equal measure by moments of opportunity and years of democratic regression. The 1980 Constitution, imposed through a deeply flawed referendum, enshrined an authoritarian presidency. Even the reforms following the 1998 Herdmanston Accord, while important, fell short of the fundamental transformation our democracy requires.

Yet today’s Guyana is not yesterday’s. Our emergence as an energy power, growing strategic importance, and unprecedented economic opportunities demand governance structures equal to these new realities. We can no longer afford the luxury of political institutions that serve partisan interests rather than national needs. The power distribution and accountability mechanisms that might have suited a smaller, poorer Guyana cannot serve a nation poised to become a regional economic leader.

In Justice Carl Singh, we have found the right person to guide this crucial process of constitutional renewal. His appointment as Chairman of the Constitutional Reform Commission brings more than legal expertise to this vital task – it brings the wisdom gained from years of judicial service and an unimpeachable record of professional integrity. Throughout his career on the bench and as Chancellor, Justice Singh demonstrated legal acumen and a deep commitment to justice and fair play. His reputation for competence, professionalism, and patriotic dedication to Guyana’s development makes him uniquely qualified to lead this reform process.

However, the Commission’s progress has been marked by an unfortunate combination of institutional lethargy and a conspicuous lack of political will. While submissions continue to trickle in, they often mirror the narrow scope seen in budget discussions – tactical adjustments rather than the transformational changes our nation requires. This incrementalist approach threatens to squander a historic opportunity for meaningful reform.

Two critical issues demand immediate attention within this broader reform agenda: the constitutional entrenchment of the Natural Resource Fund (NRF) and the establishment of an independent petroleum commission. These aren’t merely technical adjustments but fundamental reforms that would help safeguard Guyana’s resource wealth for generations to come. Without constitutional protection, the NRF remains vulnerable to political manipulation and short-term thinking. Similarly, without an independent petroleum commission enshrined in our constitution, the oversight of our energy sector risks being compromised by partisan interests.

These resource governance reforms must be integrated with other essential changes. Political party accountability and transparency in campaign financing can no longer remain in the realm of rhetoric – they must be institutionalized. The concentration of power in the presidency, a relic of a less democratic era, requires fundamental revision. The separation of Head of State from Head of Government would create necessary checks and balances while maintaining effective governance.

A second legislative chamber would provide the deliberative space our democracy needs for complex national decisions. Opening the political arena to independent candidates would break the stranglehold of party politics that has for too long limited our democratic options. Decentralization must move beyond administrative convenience to become a genuine transfer of power to local communities.

As Walter Rodney reminded us, “The people’s struggle for genuine democracy requires mechanisms to control those who would control the people’s destiny.” These words resonate particularly strongly as Guyana faces decisions about resource management and development that will affect generations to come. The introduction of citizen-initiated referenda and other mechanisms for direct participation becomes essential as these decisions grow more complex.

The reform process under Justice Singh’s leadership offers a path forward. His reputation for methodical, principled leadership suggests he will approach this task with the same dedication to national interest that has characterized his entire career. If anyone can transform these crucial reforms from aspirational goals to constitutional reality, it is Justice Singh. His methodical approach to legal and institutional challenges, combined with his deep understanding of Guyana’s governance needs, positions him perfectly to:

- Develop constitutional provisions that protect the NRF from political interference while ensuring its effectiveness as a sovereign wealth fund

- Design an independent petroleum commission with the authority and autonomy to properly oversee our energy sector

- Create mechanisms for transparency and accountability that will build public confidence in these institutions

- Integrate these reforms into a broader constitutional framework that serves Guyana’s long-term development needs

Our current moment – with its combination of economic opportunity and political necessity – offers a rare chance for fundamental reform. We must ensure that our democratic institutions evolve to match our national ambitions. While the process may be moving slowly, Justice Singh’s leadership gives us reason for cautious optimism. His record suggests he will approach this task with the same quiet competence and unwavering commitment to national interest that has marked his entire career.

The choice before us is clear: we can either develop political institutions worthy of our emerging status or allow democratic underdevelopment to constrain our national potential. The time for half-measures and narrow thinking has passed. Under Justice Singh’s guidance, we have an opportunity to create constitutional frameworks that will protect and maximize the benefits of our resource wealth for all Guyanese. Our responsibility is to support this process while maintaining clear focus on the essential reforms our democracy requires.

Campaign Financing in Guyana – A Crisis of Integrity

For nearly 60 years, since Guyana transitioned to proportional representation in 1964, the absence of campaign financing rules has left political parties hostage to drug dealers, money launderers, and wealthy elites. This failure has corroded governance, with decisions shaped more by financiers’ interests than the public good. Political parties, once expected to champion democratic values, now depend on illicit funds to maintain their relevance or dominance. Meanwhile, democracy in Guyana has steadily shrunk, as evidenced by political leadership making policies that serve elites instead of the population.

A particularly troubling feature of the current system is the dual role played by financiers, who contribute both to election campaigns and directly to political parties. There is widespread suspicion that contractors inflate government contract prices and secretly share the excess value with ruling parties. This practice not only robs taxpayers but also entrenches corruption, distorting governance to prioritize special interests over public welfare. Making matters worse, political parties in Guyana operate outside financial accountability laws and rarely observe anti-money laundering requirements, allowing illicit money to flow unchecked.

The reliance on “black money” — funds from drug dealers, money launderers, and wealthy elites — has created a dangerous cycle of dependency for political parties. Decisions that should serve the nation are instead shaped by the needs of financiers. This reality undermines public trust in the electoral process, as policies increasingly favor the wealthy few at the expense of the many.

Globally, the unchecked influence of money in politics highlights the risks of inaction. In India, corporate and illicit financing has corrupted elections, sidelining grassroots movements and deepening inequality. Similarly, in the United States, billionaires like Elon Musk wield outsized power, using their financial resources to dominate political narratives. Without reform, Guyana risks following this path, where elections become contests of wealth rather than ideas.

The ruling party’s misuse of state resources for political campaigning compounds these problems. National programs and projects often double as vote-buying mechanisms, blurring the line between governance and campaigning. This practice creates an uneven playing field, disadvantaging opposition parties and eroding trust in democratic institutions. Guyana’s political landscape increasingly resembles an oligarchy where power serves financiers and entrenched interests rather than the electorate.

The consequences of inaction are dire. Without meaningful reform, political parties will remain beholden to their financiers, policy decisions will skew toward the wealthy, and public disillusionment with democracy will deepen. Elections will cease to reflect the will of the people and instead serve as instruments of elite control.

Urgent reforms are needed to address this crisis. Contribution limits should cap donations to prevent undue influence, while transparency rules must require the public disclosure of all funding sources and expenditures. Political parties should be brought under financial accountability laws and compelled to comply with anti-money laundering regulations. Independent oversight is critical to enforce these rules, with significant penalties for violations.

Campaign financing is not just a technical issue; it is a fundamental threat to Guyana’s democracy. Decades of neglect and failure by political leadership have allowed corruption and inequality to thrive. Yet, it is not too late to act. By implementing these reforms and demanding accountability, Guyana can restore integrity to its electoral process and ensure that elections once again reflect the true will of the people, not the interests of a privileged few.

Understanding the Resource Curse and Dutch Disease

The “resource curse”—sometimes called the paradox of plenty—describes the counterintuitive phenomenon in which countries rich in natural resources experience slower economic growth, weaker development outcomes, and heightened governance challenges compared to resource-scarce nations. Linked closely to this concept is “Dutch disease,” an economic condition that arises when the exploitation of natural resources leads to currency appreciation, undermining other sectors like agriculture and manufacturing.

The term “Dutch disease” originated in the 1970s, following the economic struggles of the Netherlands after discovering natural gas in the Groningen field. The subsequent inflow of foreign currency caused the Dutch guilder to appreciate, rendering exports from other sectors less competitive and leading to industrial decline. While broader in scope, the resource curse encapsulates this economic dynamic and adds layers of political and social consequences—including corruption, authoritarianism, and poor institutional development.

Resource-rich nations often become overly dependent on resource revenues, exposing their economies to price shocks in global commodity markets. Governments struggle to maintain public spending and economic stability when resource prices fall. Dutch disease exacerbates these issues by reallocating resources toward the booming resource sector, crowding out investment and labor in other industries, leading to a diminished industrial base and a lack of diversification. Resource wealth can also undermine political accountability by enabling rent-seeking behavior. Governments reliant on resource revenues may neglect taxation and fail to build robust institutions, exacerbating corruption and eroding public trust. Moreover, the concentration of resource wealth often benefits a small elite, while the broader population sees limited improvement in living standards. This inequality can lead to social unrest and perpetuate cycles of poverty.

Guyana provides a compelling contemporary case study of the resource curse dynamics. Following significant offshore oil discoveries, Guyana’s GDP growth has surged. However, the country has experienced other challenges typically associated with resource wealth. Unlike the classic Dutch disease case of currency appreciation, Guyana faces a foreign exchange shortage, partly because much of the income from oil is paid out rather than reinvested domestically. This limits the availability of foreign exchange for broader economic activities, exacerbating existing inequalities.

One of the most striking challenges is the uneven distribution of oil wealth. A small group of political elites, their families, and close associates reap significant benefits from resource revenues, while the majority of the population is left behind. To appease the poorer segments of society, the government has resorted to cash handouts. While these payments provide temporary relief, they fail to address structural inequities and long-term poverty. Instead, these handouts create dependency and undermine incentives for sustainable economic participation, making it harder to achieve broad-based development.

Governance challenges compound these issues. The ruling party has normalized practices that undermine accountability and good governance. There is a visible disdain for opposition voices and independent critics, even when they pose no political threat. This intolerance, combined with the opacity in government dealings, has created an environment in which corruption and greed thrive. Some ministers and party functionaries appear to prioritize personal financial gain over public service, with the Vice President openly endorsing profit-making pursuits despite the evident conflicts of interest. This culture of impunity deepens public frustration and weakens trust in institutions. The personalist nature of Guyanese politics—where decisions are centralized around key individuals rather than processes—exacerbates these problems, making governance less transparent and less accountable.

One of the most glaring examples of governance issues is the failure to establish a promised Petroleum Commission, a key institution meant to ensure transparency and oversight in the oil sector. The plan for such a commission was overruled by the Vice President, who wields immense power and answers to no one. Despite his history of questionable judgment, the Vice President continues to operate with opacity and exhibits a troubling willingness to manipulate facts to suit his narrative. This centralization of power, coupled with a lack of accountability, is emblematic of Guyana’s governance challenges and amplifies the risks associated with the resource curse.

The government’s approach to public spending and borrowing also raises concerns. There are indications that Guyana is engaging in borrowing and public spending without thorough feasibility studies or long-term planning, which could lead to unsustainable debt levels. Additionally, the rapid influx of oil revenue has increased demands on infrastructure and public services, but the pace of development often lags behind, creating bottlenecks and inefficiencies.

Many other resource-rich countries have faced similar challenges. Nigeria, for instance, has struggled with volatility due to fluctuating oil prices. Poor planning, corruption, and a lack of economic diversification have perpetuated cycles of underdevelopment and political instability. Similarly, Venezuela, once among the wealthiest nations in Latin America, has experienced economic collapse due to overdependence on oil revenues. A lack of feasibility studies, unsustainable borrowing, and mismanagement of funds exacerbated the crisis. Kazakhstan’s resource wealth has created economic imbalances and governance challenges, while Angola’s borrowing heavily against future oil revenues has led to debt traps. In Equatorial Guinea, poor governance and lack of transparency have resulted in minimal benefits for the broader population, leading to stark inequality.

Avoiding the pitfalls of the resource curse requires proactive measures. Transparent resource management, robust anti-corruption frameworks, and mechanisms for public oversight are critical. Like Norway’s Government Pension Fund, Sovereign wealth funds provide a model for responsibly managing resource revenues. Policymakers must prioritize investments in sectors like education, technology, and agriculture to reduce reliance on resource revenues. Promoting value-added industries can foster resilience against commodity price shocks. Managing currency appreciation through tools like sovereign wealth funds and monetary policy can help mitigate Dutch disease. Stabilization funds can smooth out revenue volatility and protect fiscal budgets from price shocks. Redirecting resource wealth toward health, education, and infrastructure ensures broader societal benefits and addresses inequality. Conditional cash transfer programs can directly uplift vulnerable populations.

The resource curse and Dutch disease are not inevitable outcomes for resource-rich nations. With sound policies, transparent governance, and a commitment to equitable development, Guyana can harness its natural wealth to foster sustainable growth and prosperity. The critical challenge lies in resisting the allure of short-term gains and building a foundation for long-term resilience and equity.

The Elusive Path to Corporate Governance in Guyana: A Legacy of Failed Reform

Guyana stands alone among major CARICOM nations without a formal corporate governance code, a void that has enabled troubling corporate behavior in both public and private sectors. This regulatory vacuum has become particularly glaring with the recent controversial privatization of Banks DIH Limited, one of the nation’s most iconic companies, in a transaction that epitomises the weaknesses in Guyana’s corporate governance framework.

The Banks DIH case represents perhaps the most high-profile example of corporate governance challenges in recent memory. The company’s directors effectively privatised the operating company by creating a holding company structure, forcing shareholders to exchange their shares in the operating company for shares in the new Banks DIH Holdings Inc. This maneuver, achieved through a Scheme of Arrangement approved by unsuspecting shareholders and the court without input from key regulators raises serious questions about minority shareholder protection and regulatory oversight.

The transaction’s troubling aspects are numerous. The Securities Council – the primary regulator – was notably absent from the court process that approved the scheme on what appears to be incomplete information. The directors declared existing shares “invalid” before receiving regulatory approval for the new structure. Most concerningly, shareholders were forced to exchange shares in a company with approximately $50 billion in retained earnings for shares in a new entity with none, all egregiously with no provision for dissenting shareholders.

From all appearances, the directors’ approach disregarded shareholder rights and regulatory authority. Even basic questions about the comparative value of the shares and future dividend prospects went unanswered. The Guyana Stock Exchange’s subsequent suspension of trading in Banks DIH shares created further complications for shareholders, particularly institutional investors and pension funds.

Sadly, this is not an isolated incident. Guyana has witnessed several spectacular corporate failures, each highlighting different aspects of the governance vacuum. The collapse of Globe Trust Investment Company Limited (GTICL) in 2001 came after years of operating losses, leading to civil suits against directors and the CEO for breaches of duties. The Trinidad entity Colonial Life Insurance Company (CLICO) was a governance failure, resulting in a loss of some US$30 million to Guyana’s National Insurance Scheme.

Guyana’s regulatory framework is weak and deeply rooted. While the country has accumulated numerous laws governing corporate behavior – from the Companies Act to the Securities Industry Act – enforcement remains problematic. Several companies ignore basic requirements like filing annual returns and financial statements, undeterred by the modest sanctions for non-compliance.

In some cases, it is not for lack of effort. The Securities Council 2003 published a draft of Corporate Governance guidelines in 2003 which was totally ignored. The Private Sector Commission’s 2011 code, while containing progressive provisions like mandatory separation of Chairman and CEO roles and requirements for independent directors, lacks teeth. Ironically, even PSC officials’ own companies failed to adopt these standards, with key figures pouring scorn on the idea of a mandatory code.

The challenges are particularly acute in Guyana’s context as a small developing country. These include a limited pool of qualified directors, difficulties in applying the concept of independent directors, and the dominance of family-owned businesses. State-owned enterprises present additional complications, operating under the Public Corporations Act but subject to political control.

This governance vacuum becomes increasingly concerning as Guyana experiences rapid economic growth driven by oil discoveries. The path forward requires fundamental reforms on multiple fronts. At its core, Guyana needs to establish a mandatory corporate governance code backed by genuine enforcement powers, moving beyond the voluntary guidelines that have proven ineffective. This must be paired with significant strengthening of regulatory bodies, ensuring they have clear authority and adequate resources to oversee corporate behavior effectively.

The Companies Act pays particular attention to minority shareholders, with formal mechanisms established for dissenting shareholders to voice concerns and seek redress. The judiciary, too, is expected to uphold corporate governance principles, which the relevant regulator will enforce.

Recent experience has shown, however, that the need for reform is urgent. As the Banks DIH case demonstrates, even long-established companies with strong reputations can take actions that compromise shareholder rights when operating in a weak governance environment. Until comprehensive reforms are implemented, Guyana’s shareholders remain vulnerable to corporate actions that, while perhaps legally constructed, fail to protect minority interests or promote good governance practices.

This situation cannot continue if Guyana hopes to attract and retain investment in its rapidly growing economy. As neighboring CARICOM countries have shown through their adoption of formal governance codes, the path to better corporate behavior exists. What remains to be seen is whether Guyana can summon the political will and regulatory resolve to follow it.

The Government of Guyana must act expeditiously to introduce a binding Code of Corporate Governance. Meanwhile, directors and officers of all companies must act within the framework of the relevant laws, their own corporate instruments and good corporate practices.

And regulators must not be hesitant or afraid to impose the penalties provided by law.

Conclusion

Budget 2025 intertwines economic management with electoral politics, potentially compromising fiscal discipline. While projecting 10.6% GDP growth and 13.8% non-oil sector growth, the budget lacks comprehensive stakeholder consultation and risks reduced tax revenues.

The budget reveals significant governance gaps through limited accountability for entities receiving substantial allocations like NDIA and CHPA, opaque discretionary funds totaling $9B for “targeted interventions,” and inadequate project management for key initiatives including Gas-to-Energy and the Demerara Bridge. Despite increased social spending, the untargeted cash grant distribution raises concerns, alongside unaddressed NIS policy reforms, weak campaign finance regulations, delayed constitutional reform, and ineffective Access to Information and Procurement Acts. The questionable quality of national statistics further compounds these issues.

The oversight system remains outdated despite growing budget complexity. While private auditing firms effectively monitor state corporations, this approach should extend to ministries and departments. Establishing a Budget Committee with financial experts and modernising parliamentary procedures are essential for improved resource management.

We anticipate constructive debate on these issues while emphasising the urgent need for institutional reform and enhanced governance accountability.