Today, January 26, is the 76th Anniversary of the Republic Day of India. The nation celebrates this occasion with flag raising, parades, official speeches, political and cultural events in India and in the Indian diaspora worldwide. In honour of the occasion, here’s a small sample of Indian poetry.

Today, January 26, is the 76th Anniversary of the Republic Day of India. The nation celebrates this occasion with flag raising, parades, official speeches, political and cultural events in India and in the Indian diaspora worldwide. In honour of the occasion, here’s a small sample of Indian poetry.

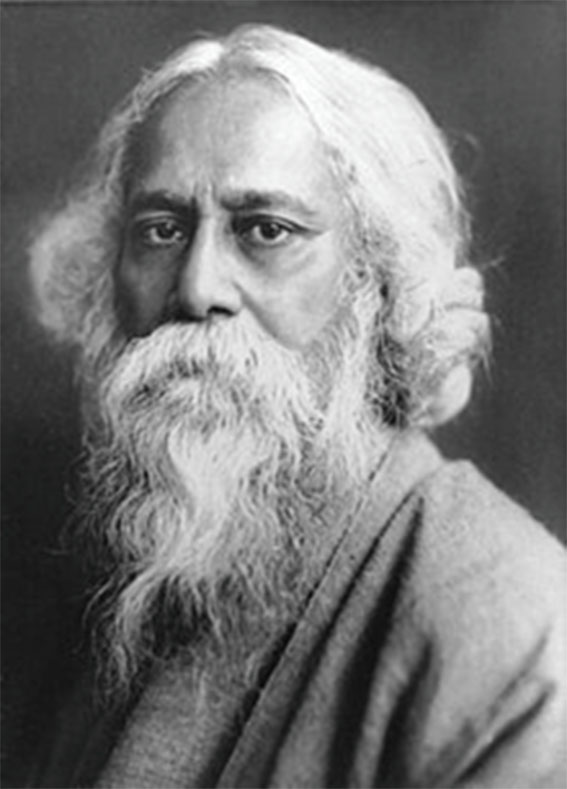

India became a republic and adopted its own constitution in 1950. It had obtained independence from Britain in August, 1947 and the partition of India took place when the country was separated from the newly created nation of Pakistan. On January 26, 1950, the British head of state was replaced by an Indian president. In the meantime, Indian literature, led by the international recognition of the work of Rabindranath Tagore, was, like the young nation, developing and slowly gaining acknowledgement.

The British Raj had direct rule over India between 1858 and 1947 when agreement was reached about independence following the independence movement led mostly by Mahatma Gandhi. The agreement was between British Governor Mountbatten and Congress Party leader Jawaharlal Nehru on the one hand and Muslim leader and separationist Mohammed Jinnah on the other that India (with its Hindu majority) would gain independence on August 15, 1947, as a separate nation from Pakistan, a newly created independent state with a Muslim majority. Nehru became the first Prime Minister of India while Jinnah was the first Governor of Pakistan.

The politics among Hindu, Sikh and Muslim factions was violent and it was a devastatingly bloody separation. But as the nations settled, their literature was experiencing its own brand of struggle in development. The two literatures avoided bloodshed but were not quite free of conflicts – colonial and ethnic politics in their development and world impact. The main battlefield was the United Kingdom where most of the publishing and some of the writing were taking place. The conflicts arose out of independence movements, a period of decolonisation, Indian and Pakistani migration to Britain and the ethnic struggles of the immigrant communities there. Colonies and former colonies from Africa and the West Indies had similar experiences.

Writing in English in India had a long period of growth and had its greatest advancement internationally when Tagore won the Nobel Prize in 1912. He remains India’s greatest writer, famous for his lyrical poetry and drama. His work made the most telling impact for several decades as a number of fiction writers and poets emerged in India and the UK. To a large extent, their work reflected the colonial situation and mainly advanced social realism. It joined a growing corps of writing that became known as Commonwealth Literature, a term that began to grow unpopular. It grouped together writings from countries belonging to the Commonwealth but did not include the British – generally, it covered countries which were once colonies of Great Britain.

It was, therefore, not a homogenous grouping, but one which, it seemed at one stage, was on the periphery of English literature. Resistance to the name became stronger and was articulated by Indian writers and critics led by prize winning novelist Salman Rushdie who declared that “Commonwealth Literature does not exist”. As Indian literature gained momentum internationally, it challenged the notion of being on the periphery of English literature, particularly if that was regarded as inferior. Indian literature was, of course, even before independence, increasingly published in English and in England.

As the twentieth century grew old, there emerged writings in English by Indians that challenged any attempt to keep them out of the hallowed halls of English literature. This was led by Rushdie, who objected to being called “Commonwealth”, along with others who came before him, and after. These include the highly decorated novelist R.K. Narayan, Anita Desai, Rohinton Mistry, the poet Kamala Das, Eunice de Souza and the prize winning novelist and poet Vickram Seth.

English language had long ago ceased to belong to the English, but there were still modes of separation of this work from English literature. Yet, even the term English Literature was avoided by Commonwealth territories because of its colonial associations and it was a mark of decolonisation when universities around the Caribbean and the Commonwealth started to use the term “Literatures in English”, having already discarded “Commonwealth Literature”.

However, Indian literature by the last quarter of the twentieth century, had imposed itself upon the world. It had established a presence in the UK to the extent that it had helped to transform English literature significantly. Fiction writers such as Rushdie, famous for “Midnight’s Children” and “The Satanic Verses”, and Seth, renowned for the novel “A Suitable Boy” have been foremost contributors to what developed as post-colonial literature in the twentieth century.

Post-colonial literature is an important development in modern literature and involves not only Indian writers but Indian literary critics are foremost in its articulation. One of these is Homi Bhabha, academic, critic and literary theorist one of the leaders in post-colonialism. Another is Gayatri Spiak, academic, feminist critic and literary theorist, who developed the theory of the sub-altern.

Indian literature is therefore a part of one of the most important literary developments that has its origins in the conflicts involving minority immigrant communities in the UK. The post-colonial writings arose from the responses of writers from India, the West Indies and Africa to the process of decolonisation at home in former British colonies and the experience as minorities in Great Britain. The political, cultural and social realities confronting ethnic minorities in Europe influenced the writing and its companion criticism and this was responsible for the use of the term Post-colonial Literature which replaced Commonwealth Literature. And this is where contemporary Indian literature may be placed.

The poetry reprinted here, however, is not from the contemporary verses, but from “the Bard of Bengal”, and from poetry that can best represent the nation of India on its Republic Day. It is from the work of Tagore (1861 – 1941), India’s greatest poet, whose most acclaimed verses in “Gitanjali” (1910) contain a prayer for his nation. It is the best of lyrical poetry and, when taken to the west, received the highest praise from W B Yeats of Ireland, who wrote the introduction to the 1912 English translation. “Gitanjali” is recognized as the deciding work that won Tagore the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, when he became the first non-European to win the award.

Tagore was born in Calcutta to a very wealthy and prominent family and grew up versed in the arts. His family was known for generous philanthropy. The literary works of this Bengali writer were a gift given to the world by Indian literature, and these selected poems are fitting gifts to celebrate the nation of India on its Republic Day.

Waiting

The song I came to sing

remains unsung to this day.

I have spent my days in stringing

and in unstringing my instrument.

The time has not come true,

the words have not been rightly set;

only there is the agony

of wishing in my heart…..

I have not seen his face,

nor have I listened to his voice;

only I have heard his gentle footsteps

from the road before my house…..

But the lamp has not been lit

and I cannot ask him into my house

I live in the hope of meeting with him

but this meeting is not yet.

Rabindranath Tagore

from Gitanjali

I

Thou hast made me endless, such is thy pleasure. This frail vessel thou emptiest

again and again, and fillest it ever with fresh life.

This little flute of a reed thou hast carried over hills and dales, and hast breathed through it melodies eternally new.

At the immortal touch of thy hands my little heart loses its limits in joy and gives birth to utterance ineffable.

Thy infinite gifts come to me only on these very small hands of mine. Ages pass, and still thou pourest, and still there is room to fill.

35

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments

By narrow domestic walls

Where words come out from the depth of truth

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way

Into the dreary desert sand of dead habit

Where the mind is led forward by thee

Into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

Rabindranath Tagore