By Nigel Westmaas

The constitutional history of Guyana—formerly known as Guiana and encompassing (at different times) the two colonies of Essequibo (established in 1616) and Demerara (established in 1746), along with Berbice (established in 1627)—is fundamentally intertwined with its political history. This history has been shaped by colonial conquest, conflict, dissent, resistance, monopoly control, and systemic racism, and through restrictions on voting rights for the majority of the population. Except for the Kofi-led revolutionary interregnum of 1763–1764, Guyana remained largely under Dutch and British rule, with a brief period of French control in 1782.

The Dutch West India Company that initially governed these colonies, implemented an administrative framework that afforded minimal, if any, representation for the local inhabitants. In 1732, the Dutch instituted the Court of Policy, a body composed of the Governor, five appointed officials (including the Fiscal Officer and Vendor Master), alongside five colonists chosen by the Governor from a pool nominated by the College of Kiezers (Electors), an electoral council primarily of Dutch plantation owners. One qualification for being a kiezer was control over at least 25 enslaved persons.

Early constitutional changes

In the early stages of its colonial history, the Court of Policy emerged as the central executive and law-making body. Over time, with the inclusion of financial representatives, a new entity—the Combined Court—was created. This structure differed from those found in other British colonies in the region prior to emancipation. Lutchman refers to this arrangement as the “Old Representative System,” highlighting its unique characteristics compared to the more uniform governance models of neighbouring English colonies. Lutchman further explained that this system was defined by an assembly controlled by planters and their allies, a

narrow and prejudiced minority within the colony’s population. At the same time, it is important to recognize that British Guiana did not function as one of the typical Crown Colonies, “in which the power of the Sovereign, exerted through the Secretary of State for the Colonies, is paramount in all matters.”

In 1787 a committee of the States General of Holland and the directors of the Dutch West India Company produced a report that became known as the “Plan of Redress.” The petitioners, who crafted the complaint/report largely planters and influential settlers, sought greater autonomy in local governance and for the Colony’s Court of Policy to have more say in decision-making rather than being dictated by the Dutch West India Company (WIC) and the Netherlands. In 1789, according to Hume Wrong (1923) a “single Court of Policy was set up for Demerara and Essequibo.”

With the formal British takeover of the colony under Major-General Hugh Carmichael in 1812, he terminated the College of Kiezers and this marked a significant shift, as “by this Proclamation of Carmichael’s female suffrage was introduced into British Guiana and women allowed the right of direct election of representatives to the Legislature. Prior to that, they only had the privilege of electing to the College of Kiesers(sic); the privileges were lost in 1849 and only restored in 1928.” The Court of Policy and Financial Representatives continued as the Combined Court, which persisted, with minor adjustments, even after the Guiana colonies were formally ceded to Britain in 1814. A modified College of Kiezers was re-established in the 1830s, with its members elected for life by planters. In 1831 the Guiana colonies became unified under the name British Guiana.

The Combined Court remained with incremental modifications until the partial abolition of slavery in 1834. With full emancipation from slavery in 1838, additional reforms were introduced to address the demands of a growing population of black citizens.

The ‘Civil list’ disputes followed when the Combined Court refused at times to fund the annual budget thus making it an unmanageable and uncontrollable organ of the government due to its complete control over the finances.

The emergence of a middle class around the 1880s brought shifts in political power. Many individuals, both prominent and lesser-known, became members of the colony’s growing organizations, such as the Bakers’ and Teachers’ Associations and professional groups. However, no seamless alliance existed between the working class and the rising middle class. Their relationship was marked by continuous tension, punctuated by occasional cooperation. This tension was particularly evident during the 1905 riots when many middle-class leaders urged moderation among striking workers. In the early period of their rise, it would be inaccurate to describe this group as a fully formed class, as their consciousness as a class or awareness of their class role had not yet fully developed. It is also important to recognize that, in many respects, the middle class or liberals owed their origins to the working people. This connection would later be reflected in the vocal support some members of the middle class lent to the demands of the poor, although this solidarity was often strained as their class allegiances shifted and swayed with changing opportunities.

One historian further suggested that the middle class was “composed of two conservative elements: firstly, the domestic capitalist who sought privileges similar to those enjoyed by foreign capital, and secondly, a Coloured and Black intelligentsia or professional group that desired recognition, but at the same time was wary of the similar ambitions of the Black working class.” This duality illustrates the complexity of middle-class politics, where aspirations for power and recognition were sometimes in tension with broader social and economic forces, including their relationship with the working class. This was evident in the example of AA Thorne , the Barbados-born labour leader, journalist and politician. As Walter Rodney observed, “even A A Thorne, who stood most firmly on the side of the wage earners, explicitly disassociated himself from the ‘rabble’ and the ‘centipedes’ who supposedly did the looting and the stoning.” Nonetheless, the forums and institutions established by liberal elements occasionally served as platforms for the working class to advance their own struggles.

The 1891 constitutional reform, according to Harold Lutchman (1974) was “regarded as a turning point in the political life of British Guiana, because of the belief that it was the year in which the planters were deprived of their power and influence…” The 1891 alteration led to an increase in the suffrage vote, and the College of Kiezers was abolished. This meant an increase in the number of Guyanese who were allowed to vote. From a voting electorate of 1916 in the 1850s it had increased to 4,000 about a decade after the 1891 reform. There were elections under this system in 1892, 1897,1901, 1906, 1911, 1916, 1921, and 1926 but the franchise (right to vote) remained severely limited, with at one point only 11,103 people registered to vote.

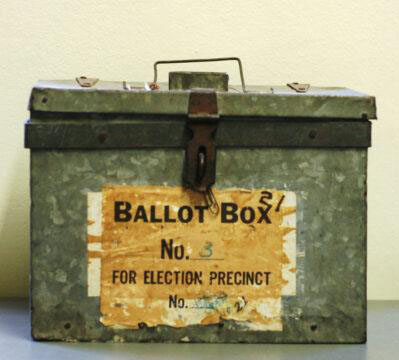

In 1896, what A R F Webber called “the greatest change in constitutional practice” emerged with the introduction of the ballot box. Immediately after this reform, in the 1897 elections, more and more “radicals,” according to Webber, captured seats. In 1898 came the introduction of annual voter registration and the Peoples Association (founded 1903), was described by Kimani Nehusi (1991) as “the first political organization to develop permanent and prolonged contact with the Guianese people” pushed for regular voter registration from this period.

Between 1909 and 1916, subtle shifts in political power became evident as elected representatives were increasingly drawn from the Black and Coloured communities gradually diminishing white dominance. By the 1920s, demographic and ethnic changes in the composition of the Court of Policy and the Combined Court had accelerated, culminating in the victory of the Popular Party in the 1926 elections.

A few individuals rose to prominence during this liberal wave in the colony, including Nelson Cannon (a locally born white politician), Webber, R E Brassington, and J P Santos. Lutchman, in analyzing their motivations, found that they were a diverse group with various personal and political motivations. Among the factors driving these men to seek public office was personal prestige, and the practice of “requisitioning candidates,” where prominent citizens would formally invite a candidate to stand for election in a specific constituency.”

The 1926 General Elections and the domination of the liberal element in its result is most attributed to the reaction of the British Government. It was certainly a very competitive election and described as being fought with “unexampled ferocity” It was preceded by several developments between parties, libel actions and the continuation of controversy over a by-election held in 1923.

The 1928 Crown Colony imposition

The 1928 imposition of Crown Colony rule in British Guiana can be classified as a constitutional coup or colonial coup from above. It was a drastic and unilateral restructuring of political power, designed to dismantle even the limited forms of local governance in favour of direct British authoritarian rule. The 1928 Constitution officially consolidated British Guiana as a Crown Colony with a Legislative Council, a significant shift in governance that came after a period of burgeoning middle-class and liberal political activity. By the time of the arrival of direct Crown Colony rule, liberal or middle-class politics in British Guiana had already reached a substantial level of activity. Historical records suggest that this rising political engagement was one of the motivating factors that led the British authorities to clamp down.

The Crown Colony witnessed the establishment of the 30-seat Legislative Council (the New Council had 14 elected members, elected in single-member constituencies under limited franchise, but were now outnumbered by 16 appointees). The Governor remained the supreme authority, while the Legislative Council was made up of both nominated and elected members, though the elected members represented a minority. The seemingly unassailable power of the plantocracy was also weakened by internal divisions and attrition in the ranks. Despite these shifts, the planters displayed remarkable resilience, often gaining the upper hand at key moments. As Rodney observed, evidence of their power lay “in their ability to raise and use public funds in their own interest and to deny revenue to the British Governor and his administration if they so chose.”

Post-war developments

Post-World War II saw increasing pressure for constitutional reform, driven by labour movements and nationalist leaders like Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham. In 1951, the Waddington Constitution was introduced, creating an elected legislature for the first time, though the Governor retained significant powers.

Following the recommendations of the Waddington Commission, significant constitutional reforms were implemented in Guyana, leading to the replacement of the Legislative Council with the House of Assembly. This marked a pivotal step in the evolution of the country’s political structure. However, the reforms faced challenges.

The People’s Progressive Party (PPP), founded by Jagan and Burnham, won the 1953 elections under this Constitution. However, fears of communist influence led Britain down the road of repression. As is well chronicled in the narrative of the modern history of Guyana, Governor Alfred Savage suspended the Constitution in October—just 133 days after it had been enacted. In place of the suspended government, Savage established a transitional administration made up of conservative politicians, businessmen, and civil servants, which marked a temporary regression in the democratization process.

By 1957, four years after the suspension, a new Constitution was implemented, the interim Legislative Council was reconstituted, this time with 14 elected members. This was the first of two Legislative Councils to be inaugurated during this period, with the second operating from 1957 to 1961. The Legislative Assembly now had more elected members, but Britain maintained control over defence, foreign policy, and internal security

The shift from FPTP to Proportional Representation

In 1961, another wave of constitutional reforms brought about the establishment of a Legislature comprising an elected 36-member Legislative Assembly, which marked a shift towards greater representation.

Before 1964, colonial Guyana used the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, inherited from British colonial rule. Under this system, candidates ran in single-member constituencies, and the one with the most votes in each constituency won the seat. This system tended to benefit parties with strong regional support, as it could grant them a parliamentary majority even if they did not win a majority of the overall votes.

The 1964 electoral reforms, imposed by the British colonial government, shifted the system from first-past-the-post (FPTP) to Proportional Representation (PR). While proponents justified the change as a means of achieving “fairer representation,” the timing and context of the reform suggest a strategic political maneuver. The shift to PR significantly altered the electoral landscape, making it more difficult for the PPP, which had consistently dominated under FPTP, to secure a parliamentary majority. Whether viewed as a necessary step toward broader political inclusivity or as a calculated effort to curb the PPP’s influence, the reform had lasting implications for Guyana’s political trajectory. Proportional Representation established a unicameral 54-member House of Assembly. Under this system, 53 members were elected through PR in a single nationwide constituency, while the Speaker was selected by the MPs. Although the PPP won the largest share of seats, the PNC-UF coalition secured enough support to form a new government under Forbes Burnham.

After Guyana gained independence in 1966, the House of Assembly was renamed the National Assembly, solidifying the transition to a sovereign parliamentary system.