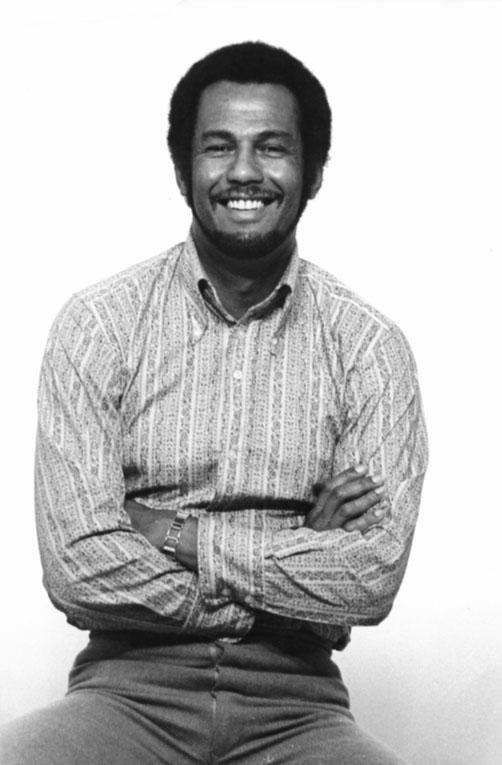

I wonder how many people reading this article have heard of Cyril Ewart Grant (better known as Cy)? I suspect not many, although he should be better known in his home country of Guyana – if only because of the significant impact he had on race relations and equal rights in the UK – far from his home country of Guyana.

I came across Cy’s name following a chance reference from a colleague as I was researching a Remembrance Day speech I was due give whilst British High Commissioner to Guyana. I was amazed to find the story of a man who was not only one of the first West Indian Officers in the RAF, but someone who also became the first person of African descent to appear regularly on UK television, and who later became a social activist dedicated to addressing racial inequality and encouraging multicultural understanding after the British inner-city riots of the early 1980s.

But who was Cy Grant and how did he end up having such an influence in the UK?

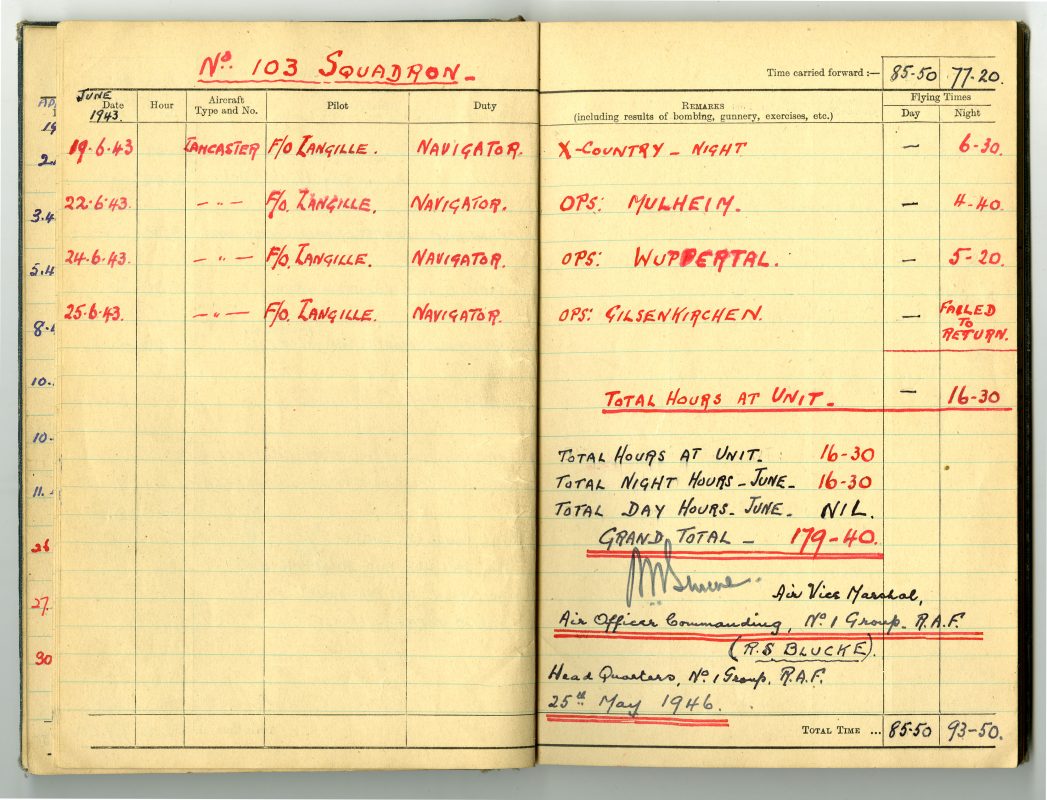

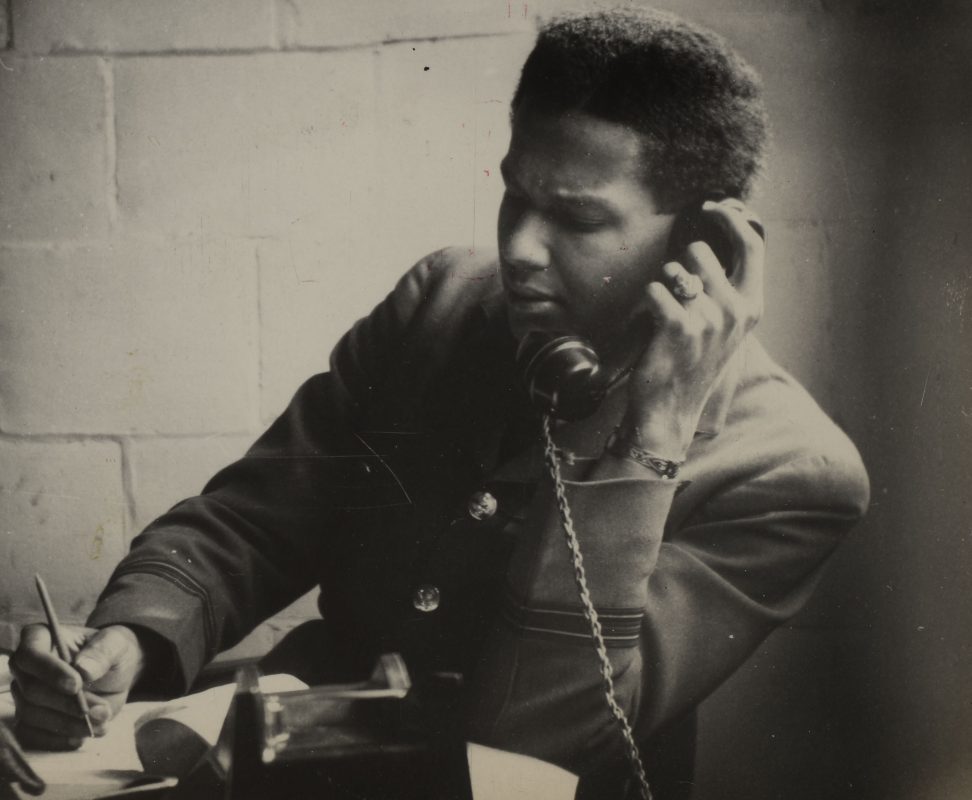

Cy was born in Beterverwagting in then British Guiana on 08 November 1919. In 1941 he joined the RAF as a Navigator – one of a handful of West Indian officers accepted at the time (and one of only four Guyanese selected to serve as aircrew).

In his autobiography, A Member of the Royal Air Force of Indeterminate Race (so named to reflect how the Nazis referred to Cy in one of their publications after he was shot down), Cy said his decision to sign-up: ‘had been prompted solely by a desire for adventure and to get away from what I foresaw would be a dull future in a British colony’. He wanted escape, he wanted adventure. Ultimately, however, he came to believe that: ‘warfare denudes you of your humanity … I feel no sense of pride’. Although this in no way diminished Cy’s respect for what his fellow aircrew had done, or his work to see that their sacrifice be acknowledged.

Cy’s operational career in the wartime RAF was, like so many others, short. He was a Navigator on a 103 Squadron Lancaster shot down on the night of 25/26 June on only the crew’s third operational mission after bombing Gelsenkirchen.

Speaking about being shot down Cy said: ‘by the time we reached the coast, we were a flaming comet over the Dutch sky. Both wings were on fire’. It soon became clear they would not reach the UK.

Cy parachuted to safety and after a short period on the run (ultimately being given up by a Dutch policeman) he was imprisoned first in Stalag Luft III, then Belaria and Lukenwalde. In a strange quirk of fate the German Commanding Officer of Stalag Luft III had actually visited British Guiana before the war.

Cy’s time in PoW camps was, in his own words: ‘equivalent to having a University education. Not only did I have an opportunity to reflect upon my life … [but] during this time I actually began to question how I got to be in this situation and to look back at my life in Guyana and what had prompted me to join up … It certainly had nothing to do with patriotism.’

In a reckoning of his Second World War experiences Cy said: ‘Being a prisoner of war … made me aware that warfare was indefensible and barbaric even when it appeared that it could be justified.’ So began a long post-war life of social activism.

Soon after the war Cy qualified as a Barrister. But his real success came when he pursued a career in acting and singing. He was the first man of African descent to make regular appearances on British TV when, in the 1950s on the satirical Tonight show, he sang the news calypso style. He had his own TV series, voiced Lt Green in Gerry Anderson’s Captain Scarlet, and starred in films and TV shows with actors such as Doug McClure, Peter Cushing, Roger Moore, Richard Burton, and Joan Collins. During the 1950s Cy also graced the front cover of The Radio Times – the UK’s leading TV-related magazine.

The significance of Cy’s TV and film career cannot be under-estimated. It occurred at a time when the UK was bitterly divided on racial grounds and when racism (‘no blacks, no dogs, no Irish’ was a common sign in guest houses and other places during this time) was all pervasive.

By the 1970s race relations in the UK were at a low ebb. Enoch Powell had made his infamous and incendiary ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in April 1968. In the early 1980s race riots broke out in many British inner cities and whilst the violence was not new to me (growing up in Northern Ireland where an anti-British terrorism campaign was ongoing) it was shocking to many people. Although, in truth, it should not have been surprising given the simmering tension and injustice which existed at the time.

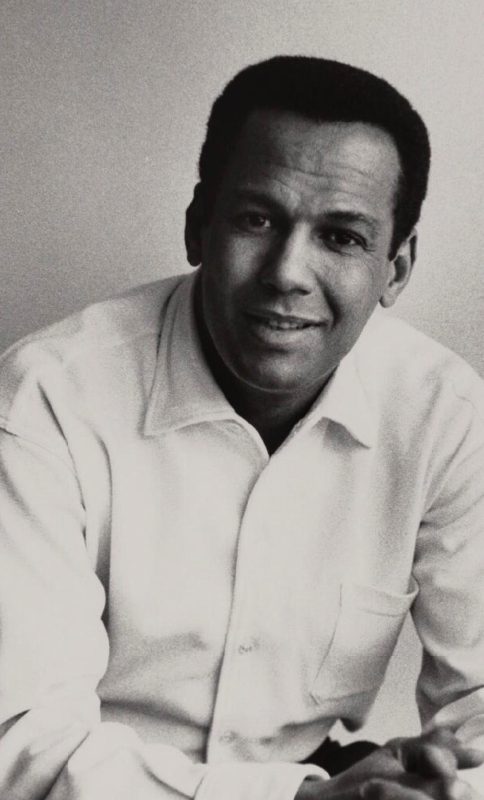

In the face of such division (and despite describing himself as ‘a very angry Black man’) Cy saw how important it was to challenge discrimination, address its root causes and improve race relations. He therefore set up the Drum Arts Centre in the 1970s (a landmark institution for Black theatre) to provide a national centre for African artistic talent. In the 1980s he was the Director of the Concord multicultural festivals – designed to foster improved race relations.

Cy campaigned tirelessly for the rights of minority groups, but also for understanding and accommodation. He appealed to our need to understand culture and the importance of our creative roots. He brought the experience of a courageous and long life in his attempts to make the UK a better place.

Did he succeed? I am the first to say that the UK is a far from perfect place, especially in these modern times. But Cy – the Guyanese from BV – played a vital role in making things better. He certainly played his part.

On 13 February 2010 Cy died, aged 90. In November 2017 a Blue Plaque was unveiled at his home in Highgate London where he had lived for 50 years before his death.

One month after his death Cy was honoured by Bomber Command at a ceremony in the House of Lords proclaiming him as an ‘inspirational example’ of how men and women of all races fought side-by-side for freedom. And notwithstanding his clear distaste of war he helped set-up an online archive to trace and commemorate Caribbean aircrew who had fought in the Second World War.

He was also a firm supporter of the Bomber Command Memorial Appeal. Whilst he didn’t live to see the unveiling of the Bomber Command monument in Green Park in June 2012 he would, no doubt, see it as a fitting tribute to the over 55,000 Bomber Command crew who died in the Second World War. That number includes two of his crewmates who did not survive on the night of 25/26 June 1943 – Jo Addison of the Royal Canadian Airforce and Sergeant RL Hollywood.

Looking back over Cy’s life he gave so much to the UK both during the Second World War, but more importantly, afterwards. He was a war hero, a poet, a musician, a songwriter, a broadcaster and an actor. But he was also a social and community activist. He stood up for equal rights in the UK and worked tirelessly to foster improved race relations during the difficult times of the 1970s and 1980s – quite the achievement.

Returning to my initial question how many people might know Cy’s story? Probably not as many as should. It is up to us to make sure his name is more widely known and appreciated. Cy was yet another son of Guyanese soil (one of many!) who had an impact far beyond the shores of the country.

The author thanks Cy Grant’s family, and especially his daughter Sami, for their support and encouragement in telling the story of their father.

About the author

Greg Quinn OBE is a former British Diplomat who has served in Estonia, Ghana, Belarus, Iraq, Washington DC, Kazakhstan, Guyana, Suriname, The Bahamas, Canada, and Antigua and Barbuda in addition to stints in London. He now runs his own government relations, business development and crisis management consultancy: Aodhan Consultancy Ltd (www.aodhaninc.co.uk).