By Nigel Westmaas

The longstanding Guyana-Venezuela land boundary dispute occupies a distinct place in the annals of regional geopolitical conflicts. For Guyanese citizens, it has posed an existential threat, looming ominously especially since independence exhibited in military hostility from Venezuela, decades and decades of diplomatic skirmishes, and ongoing border tensions.

The roots of this conflict lie deep in the colonial past, where European imperial powers casually drew borders across the New World, often indifferent to local realities and sensibilities. In the case of Guyana and Venezuela, competing historical narratives emerged, each staking claims to territories defined by imperial arbitrariness rather than geographical or cultural coherence. This intensified dramatically in the 1960s when Venezuela formally contested the validity of the 1899 Arbitral Award (which Venezuela had accepted as a “final settlement” at least until 1905) that had established the boundary with then British Guiana.

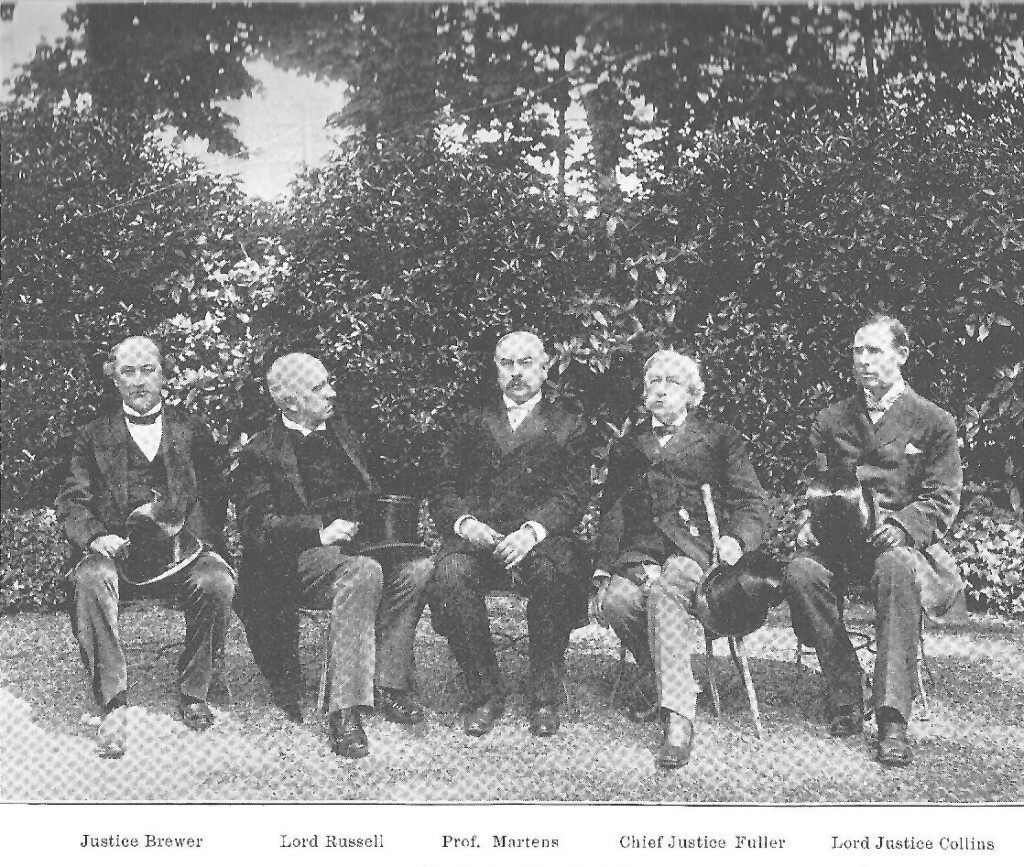

A tribunal of five arbitrators resolved the 1899 controversy between British Guiana and Venezuela, awarding most of the contested territories to Britain (now Guyana). The arbitration relied on international reputation and diplomatic pressures for enforcement rather than coercive mechanisms. The arbitrators representing Great Britain were Lord Justice Richard Henn Collins, a prominent British judge and jurist, and initially Lord Herschell (Farrer Herschell), who died early in 1899 and was replaced by Charles Russell, Baron Russell of Killowen, the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales. Represent-ing Venezuela, arbitrators appointed by the United States on Venezuela’s behalf were Chief Justice Melville Weston Fuller and Associate Justice David Josiah Brewer, both from the United States Supreme Court. The tribunal’s neutral arbitrator and president was Professor Friedrich Martens (Fyodor Fyodorovich Martens), a Russian diplomat, international jurist, and scholar. From independence Guyana’s case had to be marshalled through several mechanisms, the Geneva agreement, the UN process, the ICJ and the Joint Declaration at Argyll.

From independence Guyana’s case had to be marshalled through several mechanisms, the Geneva agreement, the UN process, the ICJ and the Joint Declaration at Argyll.

Faced with persistent territorial claims from Venezuela, education becomes a vital instrument of soft power that can include mobilizing classrooms, textbooks, and public fora to fortify national consciousness and defend territorial integrity.

Through informed public education, successive Guyanese governments have aimed to dispel misinformation, clarify national positions, and advance public dialogue. However, is this a sufficient approach? Effective public education at all societal levels must transcend being merely the government’s responsibility. It must become a strategic tool intentionally deployed to strengthen and promote national unity, particularly on issues where unity already exists. The soft power approach—emphasizing that moral, legal, and historical evidence firmly supports Guyana’s claim to the Essequibo—is a crucial and enduring element in the nation’s diplomatic strategy.

One issue is whether the historical border matter between Guyana and Venezuela is best classified as a controversy, dispute, or problem. The terms controversy and dispute are often used interchangeably in discussions on the issue. Although the term controversy appeared before the 1960s, it became particularly prominent during the period surrounding the Geneva Agreement. However, the term dispute is perhaps the most formal and precise designation. Indeed, dispute is legally recognized internationally as describing formal disagreements between states, particularly those related to territory or sovereignty. International law frequently refers to such disagreements explicitly as border disputes. Both the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the United Nations (UN) officially classify the Guyana-Venezuela issue as a border dispute, underscoring the presence of formal competing claims and significant questions under international law.

The literature on the Guyana and Venezuela boundary controversy, like the legal material in general supporting Guyana’s claim over the Essequibo is huge, ranging from official documents, seminal diplomatic assessments, academic articles published in journals, newspaper editorial commentary, and assembly of parliamentary debates dating back to the 19th century and of course the photographs and maps that continue to proliferate on the ongoing dispute.

In the late 19th century, the Daily Chronicle frequently published letters addressing the boundary question, a territorial dispute concerning British Guiana (now Guyana) and Venezuela. These discussions appeared as early as 1887, nearly a decade before the official Arbitration Award of 1899, which ultimately favoured British Guiana.

The issue continued to captivate public and political attention, particularly in the 1960s as Guyana approached independence. During this pivotal period, the press, including editorials, letters to the editor, and feature columns, actively engaged with the border controversy. Public debate intensified, reflecting growing national consciousness and the importance placed on clearly defining the nation’s territorial sovereignty prior to independence. The robust coverage by the press played a crucial role in informing the public discourse and shaping the emerging national identity around issues of sovereignty and territorial integrity.

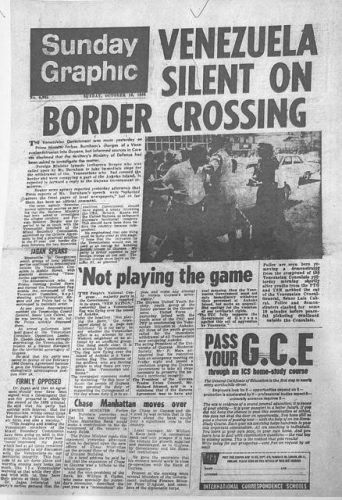

Among the headlines in Guyanese newspapers in the early 1960s include the following in the Guyana Graphic:

“Most Venezuelans unaware of border dispute – Gajraj” August 4, 1965

“When the Venezuelans invaded Guiana” (David Granger) August 8, 1965

“Venezuela not happy – rich oil strike” August 11, 1965

“Not an inch – to Venezuela says govt” October 10, 1965

“Land showdown? Venezuelan ambassador calls off talks” October 16, 1965

“No backing down – Venezuela = but we wish no war with BG in and claim” October 19, 1965

“Border talks – a moral victory over Venezuela” Guiana Graphic, October 22, 1965

“No word from Venezuela – border summit may not come off” November 3, 1965

“PPP comments on Venezuela border claim” November 6, 1965

“Police quiz Venezuelans held by border patrol”, November 26, 1965

“Venezuelan flag burnt at consulate” October 15, 1966

“Venezuela threatens our survival, says Ramphal” July 17 1968

“PM holds talks with opposition”, July 19 1968

At a more formal diplomatic level there have been plethora of Guyana foreign ministry reports for international fora defending Guyana’s position throughout the different administrations that have ruled Guyana since independence.

At a scholarly level, the works of Henry Jeffrey, Noel Menezes, Cedric Joseph, Nigel Gravesande, Cedric Joseph, Jay Mandle, Odeen Ishmael, and many others are available for informed and “armed” Guyanese.

The following chronology highlights key moments in the border controversy from the earliest period to the Argyl declaration:

Chronological timeline of key events: Guyana – Venezuela border controversy

1494: Treaty of Tordesillas: agreement between Spain and Portugal, mediated by Pope Alexander VI, intended to settle disputes over newly discovered territories.

1814: Treaty of London – Britain given Essequibo, Demerara and Berbice succeeding the Dutch

1823: Monroe doctrine: that the Western Hemisphere was closed to future European colonization or intervention. While it asserted neutrality toward existing European colonies, it warned European powers against further territorial ambitions in the Americas, implying that such actions would be viewed as threats to US interests. Over time, the doctrine shaped US foreign relations, becoming a justification for American dominance and intervention throughout Latin America, the Caribbean and Asia Pacific.

1830s: Venezuela becomes independent of Spain

1835–1840: Britain commissioned surveyor Robert Schomburgk maps British Guiana’s frontiers. Schomburgk’s survey (completed in 1840) proposed the “Schomburgk Line,” extending British Guiana’s claim by roughly 30,000 square miles westward

1841: Venezuela – which had become independent from Spain by 1830 – protested the British boundary claim as an encroachment. Caracas asserted that the true boundary was the Essequibo River, effectively claiming all territory west of the Essequibo

1844–1850: Britain offered a compromise in 1844 (giving Venezuela control of the Orinoco river mouth), but Venezuela ignored it

1876: The dispute flared up again after gold was discovered in the contested interior. Britain advanced new claims to about 33,000 additional square miles beyond the Schomburgk Line (into what Venezuela saw as its territory)

1886–1887: Britain unilaterally declared the Schomburgk Line as the provisional frontier in 1886

1887: Venezuela breaks off diplomatic relations with Britain

1876-1896: Venezuela called for US support based upon Monroe Doctrine of 1823

1887 +: US urged Great Britain and Venezuela to renew relations while offering Venezuela her sympathy

1894: Venezuela invokes Monroe doctrine, especially the Olney corollary, that is, that the British attitude represented a challenge to the Monroe Doctrine. Subsequently, in October 1894 “Venezuelan forces crossed the border into British Guiana and established a post; the British colonial police and magistrate left without putting up any resistance.”

1895: The crisis peaked with the Venezuelan crisis of 1895. US President Grover Cleveland’s administration, citing the Monroe Doctrine, demanded that Britain submit the matter to international arbitration. The Olney Corollary was an extension of the Monroe Doctrine articulated in 1895 by US Secretary of State Richard Olney. It asserted that the United States had the authority to intervene in territorial disputes within the Western Hemisphere, particularly between European powers and Latin American countries.

1897: Treaty of Arbitration launched in Washington (aka Treaty of Washington)

1899: An international tribunal in Paris issued its Arbitral Award after meeting for “some fifty-five sessions”, which fixed the boundary largely along a modified Schomburgk Line. Venezuela officially accepted the award as a “full, perfect, and final settlement” at the time.

1905: The boundary survey was completed by a mixed commission, and concrete markers were placed, finalizing the border per the 1899 Award.

1949: In 1944, Severo Mallet-Prevost, who had served as the official secretary for the U.S.-Venezuela delegation during the 1899 Paris Arbitral Award concerning the Venezuela-British Guiana boundary dispute, penned a memorandum to be published posthumously. In this document, he alleged that the arbitration decision, which largely favoured Britain, resulted from political pressure exerted by the tribunal’s president, Friedrich Martens, leading to a compromise that deprived Venezuela of rightful territory. The memorandum was released in 1949, after Mallet-Prevost’s death, and reignited Venezuela’s claims over the region whose boundaries were settled by the 1899 decision.

1962: Venezuela formally renounced the 1899 Award and revived its claim to the Essequibo region. Venezuelan Foreign Minister Marcos Falcón Briceño told the United Nations that the award was “null and void” due to the alleged collusion revealed in the Mallet-Prevost memo.

1966: Geneva Negotiations – the UK, British Guiana, and Venezuela signed the Geneva Agreement of 1966 – a treaty to seek a “practical, peaceful and satisfactory” resolution to the controversy.

In a provocative move shortly after Guyana’s independence, Venezuelan troops occupied Ankoko Island, a small border island in the Cuyuni River that is half within Guyana. Venezuela unilaterally built a military outpost there, which it maintains to this day.

1970: With the Mixed Commission’s four-year term ending without a resolution, the parties agreed to a 12-year moratorium on the dispute. Guyanese Prime Minister Forbes Burnham and Venezuelan President Rafael Caldera signed the Port of Spain Protocol (in Port of Spain, Trinidad), which put Venezuela’s claim on hold until 1982

1982–1983: As the 12-year Port of Spain moratorium approached expiry, Venezuela signaled it would revive the claim. During the 1982 Falklands War (UK vs. Argentina), Venezuela expressed renewed interest in Essequibo

1983: Venezuelan President Luis Herrera Campins refused to renew the Protocol when it lapsed, formally reasserting Venezuela’s territorial claim

1990: The United Nations Secretary-General, acting under the Geneva Agreement, appointed a Good Officer process to mediate. Over the ensuing decades, U.N.-appointed envoys engaged in talks with Guyana and Venezuela

1999–2004: Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez initially took a less confrontational tone. Under Chávez (who came to power in 1999), Venezuela focused on regional integration and at times downplayed the Essequibo claim. In 2004, during a visit to Georgetown, Chávez even remarked that he considered the border controversy “finished,” signalling a desire for warmer relations

2013: A Venezuelan navy vessel seized the seismic research ship Teknik Perdana, which was surveying for oil in offshore waters claimed by Guyana

2015: Venezuela responded forcefully to Guyana’s oil breakthrough. In May, President Nicolás Maduro issued a decree unilaterally extending Venezuela’s maritime boundaries to encompass nearly all the waters off Guyana’s Essequibo region

2018: With Guyana’s support, the UN Secretary-General formally referred the dispute to the International Court of Justice

2020: The ICJ ruled that it has jurisdiction to hear the case (specifically, to determine the validity of the 1899 Award). The ICJ ordered Venezuela to refrain from “actions that would alter Guyana;s control over the disputed area…pending a final decision in the case.”

2023: In a dramatic escalation, Venezuela held a national referendum asking its citizens whether to make the Essequibo region a formal Venezuelan state. Following the referendum, Venezuela’s National Assembly approved measures to formally annex Essequibo. Venezuela published new official maps showing the disputed 159,000 km² region as its “State of Guayana Esequiba”

December 2023 : Joint declaration in Argyle, St Vincent and the Grenadines “for dialogue and peace between Guyana and Venezuela” between President Irfaan Ali of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana and President Nicolas Maduro of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela held discussions on matters consequential to the territory in dispute between their two countries. The discussions were facilitated by the Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Pro-Tempore President of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) Prime Minister Ralph E Gonsalves