By Moses Bhagwan & Nigel Westmaas

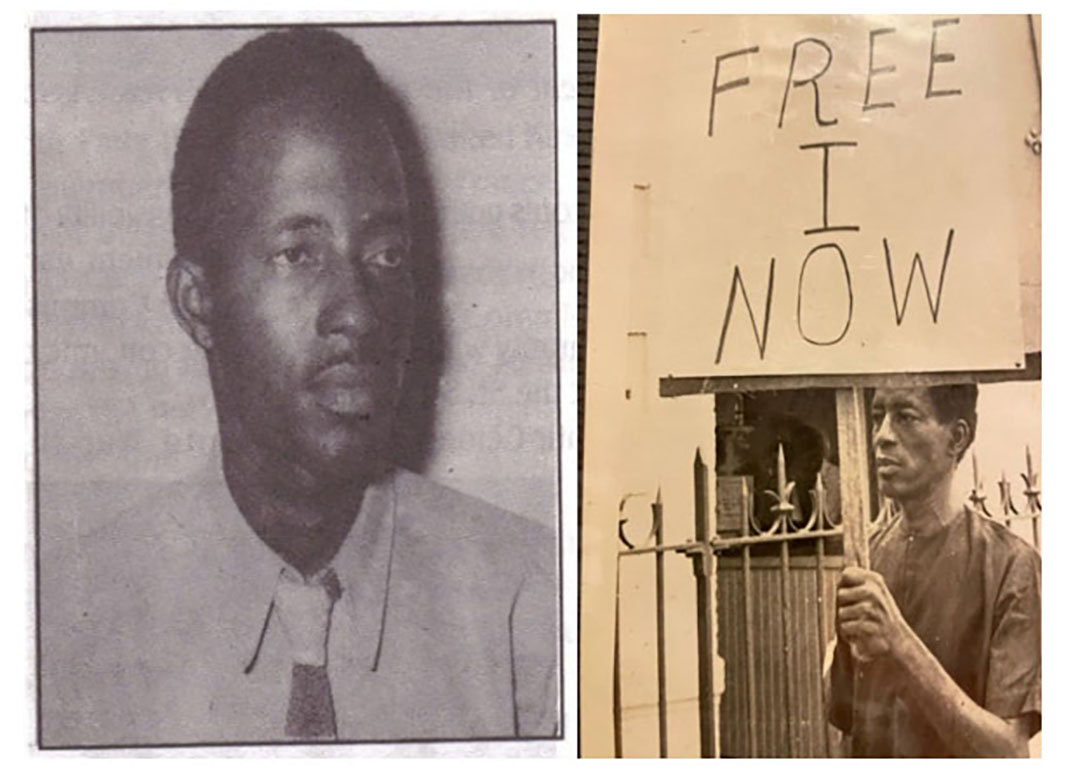

Last Friday April 4, Eusi Kwayana crossed 100 years. Born Sydney King in Lusignan in 1925, his birth year coincided with several significant global events. Sun Yat-sen, the Chinese nationalist leader, founder of modern China, and head of the Kuomintang (KMT), passed away. In the United States, the Scopes Trial famously unfolded in Dayton, Tennessee, over the teaching of evolution in schools, reflecting broader tensions between science and religion. Television technology was first publicly demonstrated, ushering in a new era in communication. 1925 was the year that Marcus Garvey was imprisoned in the US. It was the birthyear of Malcolm X, who would become a prominent civil rights leader and who was tragically assassinated in 1965.

Last Friday April 4, Eusi Kwayana crossed 100 years. Born Sydney King in Lusignan in 1925, his birth year coincided with several significant global events. Sun Yat-sen, the Chinese nationalist leader, founder of modern China, and head of the Kuomintang (KMT), passed away. In the United States, the Scopes Trial famously unfolded in Dayton, Tennessee, over the teaching of evolution in schools, reflecting broader tensions between science and religion. Television technology was first publicly demonstrated, ushering in a new era in communication. 1925 was the year that Marcus Garvey was imprisoned in the US. It was the birthyear of Malcolm X, who would become a prominent civil rights leader and who was tragically assassinated in 1965.

In then British Guiana, Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow had already established the British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU) in 1919, which by 1925 was forcefully advocating for workers’ rights. Against this backdrop Kwayana emerged as a remarkable figure whose practice transcended boundaries as a cultural activist, poet, playwright, teacher, politician, journalist, author and griot.

One of Eusi Kwayana’s earliest politically self-conscious memories dates back to Lusignan around 1929, when he was about four or five years old. He vividly recalled a woman, perhaps aged between 60 and 65, sitting in a doorway on a bench in a range yard, enjoying the warmth of the sun with her legs crossed and smoking a clay pipe. Addressing him directly, she said, “Pickney, Congo ah high nation, Congo ah high nation.” Her words, clearly affirming African pride and heritage, emphasized that the horrors of slavery could never erase the fact that Africans originated from great and dignified civilizations. Kwayana never forgot it. Kwayana and the poet Martin Carter often rode their bicycles to and from Georgetown. On one such occasion, Carter stopped at Le Ressouvenir—a site associated with the 1823 Demerara revolt—and, in a gesture echoed in the title of one of his later poems, physically listened to the land.

The Guyanese writer Jan Carew once said he remembered Kwayana as a “tall ascetic, speaking so softly you had to lean forward to hear what he was saying, looked like a black Jesus and carried an aura of gentleness around with him, but you sensed that there was implacable resolution at the core of that gentleness…” Kwayana was indeed a self-disciplined, austere figure – his diet consists of raw food, and he recalls Victory in Europe (VE) Day in 1945, when after imbibing and subsequently becoming ill, he resolved never to drink again, declaring rum unfit for human consumption.

In the 1950s, Kwayana regularly tuned into Radio Moscow on his Berec radio, balancing its broadcasts against those from the BBC and Voice of America. He bought his first ‘matchbox’ car – the brakes and radiator didn’t work very well – from the artist Aubrey Williams in 1952 for $250. He got a Morris Oxford after he became minister in 1953; given his generous nature, both cars were used for carrying people back and forth from Buxton like a free taxi.

In the 1950s, Kwayana regularly tuned into Radio Moscow on his Berec radio, balancing its broadcasts against those from the BBC and Voice of America. He bought his first ‘matchbox’ car – the brakes and radiator didn’t work very well – from the artist Aubrey Williams in 1952 for $250. He got a Morris Oxford after he became minister in 1953; given his generous nature, both cars were used for carrying people back and forth from Buxton like a free taxi.

Kwayana was an associate member of the Indian National Congress (INC) of British Guiana. The INC comprised prominent individuals such as Pandit Sama Persaud and Fred Roopchand, the latter being a Roman Catholic and gold miner. The organisation primarily operated along the East Coast of Demerara, particularly before 1947, and was renowned for publishing an annual almanac that detailed important Hindu religious festivals, feasts, holidays, and other significant cultural and religious events.

Kwayana visited Ghana (1964-65) where he met Kwame Nkrumah three times, and attended a speech given by Che Guevara.

As is well known, Kwayana along with others, including Tacuma Ogunseye, Ngozi Moses, Sase Omo and Sybil Sargeant, founded the African Society for Cultural Relations with Independent Africa (ASCRIA) in 1964. In the 1970s, ASCRIA and the Indian Political Revolutionary Associates (IPRA) came together to occupy vacant sugar estate lands and break down divides through multiracial cooperation. Moses Bhagwan recalls that “Eusi and I met secretly in a motor car in a deserted spot at Happy Acres as the sun darkened. We discussed closer working relations. He then invited me into the heart of Buxton to talk about the Cane Farmers Bill being piloted through the Parliament. We were critical of the Bill.”

While Kwayana is best known for his political activism, his contributions to political discourse extend well beyond activism. He played a pivotal role in the ASCRIA Bulletins and ASCRIA Drums, publications associated with the African cultural-political movement of the 1960s.

Remarkably, Eusi Kwayana holds the unique distinction of having composed the official songs for three major political parties in Guyana: the PPP (“O Fighting Men”), the PNC (“Battle Song”), and the WPA (“People’s Power”). How many Guyanese today know this? What is lost when this kind of history is not told?

THE SCRIBE

A “writing machine,” the Buxton sage has produced hundreds of works across multiple genres—poems, critical reviews, short stories, letters to newspapers, opinion pieces, song lyrics, obituaries, court motions, parliamentary interventions (motions and speeches), editorials, political statements, essays, press releases, and plays for both theatre and grassroots events.

His literary span stretches from The Prodigal Daughter (his first play, written in the early 1940s) to the book The Legend: Post-Emancipation Villages in Guyana, Making World History (2016), co-authored with David Hinds.

Eusi Kwayana’s recognition as poet and political lyricist at Guyana’s 2007 Folk Festival in New York underscores his immense contribution to Guyanese and Caribbean political-cultural life—a contribution that has seldom been fully acknowledged. His writings range from poignant lyricism on culture, people, and village life to the often anguished, self-effacing critique of Guyana’s political landscape—including his own role in it.

One of his most remarkable works, Buxton-Friendship in Print and Memory, exemplifies his method—a deeply democratic respect for people from all walks of life. Published by Red Thread Women’s Press (1999), this village history illuminates the minutiae of everyday life while reinforcing Kwayana’s reverence for both the printed word and the oral tradition, the latter long marginalized in formal scholarship but deeply embedded in the cultural traditions of Guyana and the Caribbean. Kwayana also wrote several plays, including Christus the Messiah, Proclamation (on the 1823 Demerara Revolt), The King and I, and the prize-winning Promised Land (1965). During the same period, he wrote theatre reviews under the alias Kiskadee Cloud.

POLITICAL FIGURE, NOT POLITICIAN

Despite his towering contributions, Kwayana remains one of the most misunderstood figures in Guyanese political history. And no political proposal has dogged him more than the call for ‘partition’ in 1961. The plan primarily advocated ‘joint and equal Prime Ministerships,’ with partition identified as a last resort. At the time, Kwayana felt that it would bring equality of rights and power for Indians and Africans and attempt to end racial antagonism.

Reflecting on this period in Caribbean Daylight (1992), a New York-based newspaper edited by Rohit Kanhai, Kwayana remarked, “My habit of looking critically at my own actions has provided other actors with a shield. This habit, which I think is a good one, provides others with cover, and all they do is add more and more to their storehouse of non-responsibility to win some quick short-lived advantage: whatever is not founded on truth will fall apart because reality has no supports on which falsehood can rest.”

Kwayana’s philosophy of multiracialism—tailored to Guyana’s unique socio-political landscape—is best captured in his celebrated 1978 speech, Racial Insecurity and the Political System. This speech laid the foundation for a self-critical assessment of racial divisions in Guyana and became integral to the WPA’s broader philosophy of multiracialism—a legacy that continues to inform contemporary debates on race and politics, even if unacknowledged. He later expanded upon this in two major analyses of the cultural contributions of Indians and Africans at the Genesis of a Nation conference held at the Pegasus Hotel in 1988.

Between the early 1970s and 1990s, Kwayana was the principal contributor (without bylines) and publisher of Dayclean, a single-sheet WPA publication produced under conditions of state repression and paper scarcity.

Kwayana’s entry in Guyanese politics was never casual, accidental, superficial or opportunistic. Throughout he conveyed a depth of meaning, gravity and sense of purpose and urgency to every manifestation of his political instincts and interventions. Few figures in our history have been as transformative or as deeply reflective. Kwayana gave extraordinary thought to the meaning of his work—its connection to the essence of our collective being, whether expressed through the individual, the village, or the nation of villages. His concern extended to children, the elderly, indigenous peoples, the infirm, and the causes of premature death. He stood firmly for the rights of women and the recognition of martyrs. No one has been more conspicuous in their openness to transformation, or more public in the evolution of their thought and action.

Kwayana was prescient (a “see far” man) in his sense of the situation, a disciplined and careful reader of context. During the 1953 elections, he made the suggestion that the PPP should not set itself the goal of winning a majority and become the government. That must have been heresy. The movement, he contended, needed time for its ideas to be more deeply rooted among the people. This suggestion (warning?) was not heeded. We know the history of the collapse of the fragile unity in 1955. You have reason to consider Kwayana a prophet. He stands among those rare political-cultural activists whose life and work define each major phase of our country’s recent history. We know of no one who could grasp the sense of a moment or situation as intuitively and comprehensively as he.

Within the WPA, when doubts arose and our vision clouded, when we found ourselves at a standstill—who else did we turn to, if not Kwayana?

Eusi affects us all in different ways. He was called the Sage of Buxton, the village politician—just two among the many titles he acquired. It is in his nature to locate and uplift the basic units of our social existence. You can find this in his writings—this attentiveness to the singular, which always added up to a man of expansive vision. His outlook embraced ideas and causes across the Caribbean, Africa, India, and the Americas.

PARLIAMENT

Renowned for his mastery of parliamentary procedure, Kwayana possesses an acute grasp of the minutiae of motions and legal frameworks. He was equally adept at exposing the limitations of Guyana’s judicial system as he was at exploiting its legal structures in pursuit of justice. He frequently filed private legal motions in support of various causes, and his legal writings—still to be compiled—would undoubtedly enrich Guyanese legal theory and practice.

Because of the limitations of the 5th parliament (1986-1992) and his own preferred mode of representation, Kwayana made the WPA office and his frequent visits to villages and the rural areas “centres of representation,” turning Parliament into a “living forum.” He reopened the use of citizen petitions to the National Assembly as a means of expressing grievances. Outside of Parliament, the WPA MP, helped by other WPA activists, assisted senior citizens; mothers due for social impact amelioration payments; farmers with water problems; and persons denied the reasonably prompt issue of passports. He visited the Georgetown hospital on several occasions, taking extensive notes of its deficiencies and speaking with patients. These were only a few of the representations he made.

In August 1987, the WPA MP physically stood with protesting crowds as the kero and gas crisis unfolded. His words were vigilant on the deprivation and abuse of the working people: “So long as suffering of this kind is encouraged and maintained by the government my pen will not sleep in my hand, nor will my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.”

What were the origins of Kwayana’s skill in the Parliament? A likely possibility was his generation’s experience from the 1940s to the 1960s, with its ingrained knowledge of the ‘system’ when fighting British control of the legislature and colony. Cheddi Jagan, Forbes Burnham, HJM Hubbard, Janet Jagan, Winifred Gaskin, WOR Kendall, Boysie Ramkarran and others all exhibited a range of parliamentary prowess during their own shifts in the Chamber. These parliamentarians were forced to be creative and knowledgeable of the system out of sheer necessity to ensure their survival against the British constitutional and colonial system.

Decades later, in the early 1970s, there is the true-life incident told by a visiting journalist from the US affirming Kwayana’s incorruptibility. According to the New Yorker report, “after a paid state visit to Africa, he (Kwayana) received a thousand-dollar check for “additional expenses and inconveniences.” He sent it back, received another check, and returned that too, with a note saying he had not had any additional expenses and, furthermore, had “not been inconvenienced in the least.”

We have all been ‘convenienced’ by the 100 years that Eusi Kwayana has lived on this earth.

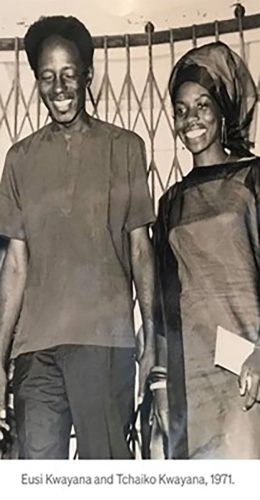

Happy born day, brother Kwayana. We salute you, your sons Alaf and Kofi, your daughter Iyabo, and your late great partner in life, sister Tchaiko Kwayana.