Norma Rae is a 1979 film about a textile mill factory worker who joins a union to challenge her employers after her workplace compromises the health of co-workers and herself. At first glance it seems an unusual choice for a tribute to mothers for Mother’s Day tomorrow. Nothing new this week at the cinema presented itself as an adequate tribute to mothers, so I dug into film history for an appropriate one.

Popular film has a familiar trope for many female protagonists of a certain age – examining their worth as characters through the prism of their relationship with their children – but there was a deft message in Norma Rae that made me sit up as I re-watched it this week. The film is a loose depiction of a real incident which occurred in 1975 and in 2017 it still has relevance for poor, working women the world over.

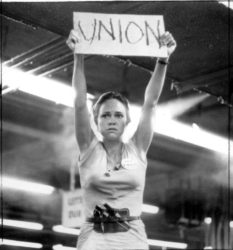

Mother’s Day will find many poor mothers tomorrow reluctant to accept the coming of Monday, when they will return to poor paying jobs where their rights are diminished. Norma’s journey from being a pushed-around woman to the unwitting saviour of her co-workers is a heart-warming, but not sentimental one. Buoyed by a human rights lawyer and disheartened by the lack of a union, Sally Field’s Norma takes a defiant stand during rush hour, stopping work and holding up a sign that says ‘UNION.’

After being arrested and making bail, she returns home like a wounded soldier, and makes her way through the house. The scene that follows is the crux of my focus today. What now? Will she rail against the injustices meted out to her? Will she sob? Will she rave? No, she heads to her children’s bedroom.

She rouses them from bed and takes them to the living room. She is ready to confess her soul and tells them, “Your mom is jailbird. Now, you’re gonna be hearin’ that, and a lot of other things. But you’re gonna hear it from me first.” All three children are under the age of 11. At this point, they might not even understand the what and why of Norma’s treatise. But it’s an important moment for Norma to face herself and to lay herself down for judgement. Imagine what a woman with three children, each from different fathers, would have endured in that era. Imagine what that same woman would endure in this era, especially when she’s working for minimum wage. It should be a non-issue, but it’s not. There’s not so much the sense that Norma is embarrassed of herself but a matter-of-factness in the way Fields portrays her with calm, defiance and self-acceptance. She tells her children that they each have fathers, including a dead former husband and another a man she does not know much. “I’m not perfect. I made mistakes,” she says, without sentiment, or even regret.

In an earlier scene, she admits that sometimes she’s too much. Sometimes, she’s not a very nice person. But this isn’t a film called Saint Norma. Sally Field, unlike some of her contemporaries, is not a chameleon who is adept at sinking into varying roles. She has a type, and is an expert at carving new creations from the familiar template of the woman who is barely keeping it together for the sake of her family and for the sake of her own sanity until the pressure is too much.

She tells them, “If you go in the mill, I want life to be better for you than it is for me. That’s why I joined up with the union, and that’s why I got fired for it. You understand me? Now, you kids… you know what I am. And you know that I believe in standin’ up for what I think is right.”

Her fear that this is their future is distressing, but we realise that she’s very likely correct. Pulling oneself up by the bootstraps from poverty is easier said than done, and we see it daily on the streets where vending mothers are forced to bring their children into the business, or labouring mothers out of the city are forced to do the same. It’s a stark reality that becomes familiar for many minimum wage working mothers all across this country, and the world.

And yet, like in Field’s performance, there is defiance that comes with this knowledge. They might be stuck in the mill, but they’re not going to lay down and accept just anything that comes their way. This a battle cry for future generations. More significantly, though, it’s an affirmation from Norma to herself representing her entire ideology. She is who she is and she’s going to stand up for what she believes in, no matter what the future may hold. It’s a message working mothers deserve to consider tomorrow. The scene, like the undervalued aspects of motherhood, is no loud and brash showpiece but quiet in its firmness. And like the film it builds to become a tribute to mothers who work, the ones in the less glamorous careers, the ones with children under ten, the ones with children whose fathers they do not care to know, the ones who will be missed by the rapid commercialisation of the day and instead wake up tomorrow to go to vend at a market, or in someone’s Regent Street store. For them, the battle wages on.

Have a comment? Write to Andrew at almasydk@gmail.com