The ownership of land at Calabash Lake, near Queenstown on the Essequibo Coast, reportedly included in the Amerindian reserves, is being contested by Queenstown residents, who believe it was bought by their ancestors.

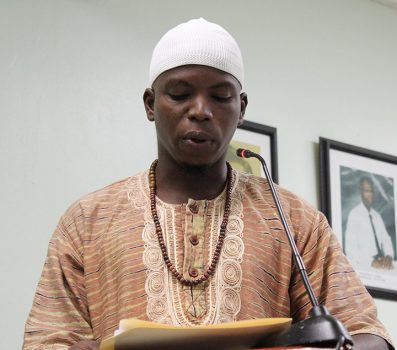

The claim was made on Thursday before the Commission of Inquiry set up to investigate African ancestral and other land matters, and was brought before the tribunal by Cornell Beaton.

Queenstown resident Beaton, who identified himself as a social worker, stated that residents believe that the section of land was included in the lands bought by freed African slaves.

“There was evidence that our ancestors had demarcated the boundaries of this land as it was a part of the agreement in the terms of purchase. However, sir, there has been an unprecedented act of usurping of ancestral lands and cover-up. We say this because when the Amerindian boundaries were drawn, this stretch of land was included in the area of reservation and we have been asked by persons in authority to withhold information and evidence on their acquisition of this land,” Beaton stated.

He told the commission that Queenstown had been sold to 15 freed Africans for $15, and explained that the agreement took the form of an absolute grant.

The witness said that he has not observed any Amerindians occupying the space, but noted that persons have been logging in the area, although he could not comment on whether this activity was legal or not.

“…I would like to bring you to the grant that says that they paid $15, that was the purchase price, and this land was given to…persons and it says their heirs, executors, administrations and assigns—and I think that should be administrators—absolutely and forever. However, it went further to say that this would be under these conditions. And the last paragraph in the document says if any of the preceding conditions are not complied with, this grant may be revoked. So while they’re saying it’s absolute, there are conditions that had to be met. And if those conditions were not met, then the grant would not have been made absolute. A grant is made absolute notwithstanding the words written into the grant; the grant is only made absolute when you would have fulfilled all the conditions, and then the Crown puts a stamp on it and says this is now an absolute grant,” Commissioner Carol Khan-James explained.

She noted that if they had not complied with the conditions, the land would go back to the state.

“So, we have to research here to see whether the conditions were kept, whether there’s that stamp to say that the grant was made absolute, before we can authenticate the statement to say, “this land belonged to my ancestors,”” Khan-James continued.

She reminded the witness that ancestral lands are determined not only through documentation, but also by occupation, citing the case of runaway slaves and the establishment of maroon communities.

“…And once there is proof that they remained there and occupied there, we can consider all of that as ancestral lands. Ancestral land doesn’t really only mean it has to be titled land; lands that were bought by the slaves. So we need to accept that. So when we make the statement about the lands were taken and given to the Amerindian community, we may not be accurate when we say “our lands were taken away,” the Commissioner further stated.

Garvey Town

The other area the residents are claiming ownership of is Garvey Town, also known as Garvey Bush, which is reportedly being continuously occupied by persons from other locations who are engaging in economic activities on the lands, to the benefit of themselves and their own communities. He also named logging as well as farming as activities being pursued in Garvey Town by these outsiders.

Describing the location, Beaton related that there are three canals running through the estates of Dageraad, Mocha and Westfield, which make up Queenstown.

“One of these such canals separates the residential from the agricultural area in Queenstown. This is the land that is under contention presently. This area is famously known as Garvey Town. It is called by this name because 100 years after the purchase of Queenstown, the village was honoured by the visit of a renowned scholar and black activist Marcus Garvey…,” he explained.

He related that the visit had inspired the descendants of those who purchased the lands to form the Marcus Garvey Association.

“…This group proceeded to develop the said area into a more residential and agricultural setting. In the 1930s, a race course was developed where horse racing used to be a featured event so as to enhance the social and economical framework of that village. The Marcus Garvey Association was known for providing and supplying the entire Essequibo Coast as well as the Suddie and the Georgetown Public Hospital with agricultural produce. This was just up to the second world war,” he said.

Beaton said that based on the evidence of the social and economic activities which occurred on the land, “it was and still is the property of our ancestors, and therefore, it should be given back to the descendants of those freed Africans, of which I am one.”

Beaaton had stated in his evidence that Queenstown was the first village to be bought by freed African slaves, but Commissioner Khan-James, who related that she is from the area, pointed out that history shows that the first village to be bought was Victoria. She also said that Queenstown was said to have been bought by Carberry, who went on to divide the land and sell portions.

“Now, I would like to know whether Garvey Bush was part of that purchase,” Khan-James stated, noting that documentation needs to be examined to prove and disprove such.

Beaton had stated that the records, which were kept at the village office, had been destroyed by fire after the change in administration.