TIFF 2020: “Night of the Kings” spins an enticing fable

In Philippe Lacôte’s moody “Night of the Kings,” telling stories becomes an act of survival.

In Philippe Lacôte’s moody “Night of the Kings,” telling stories becomes an act of survival.

In “Monday,” Argyris Papadimitropoulos takes the uncertainty that comes with exploring a new relationship and mines it for two hours as we watch a couple experience the highs, lows and everything in between of a new relationship.

In “Quo Vadis, Aida?” Jasna Đuričić stars as a Srebrenica resident whose position as a translator at a Dutch-run UN base becomes essential when members of the Serbian army encroach on the town.

Last year at TIFF, Nadav Lapid’s “Synonyms” presented the experience of an Israeli man acclimating to France as a frenetic, sensual bacchanal of chaos.

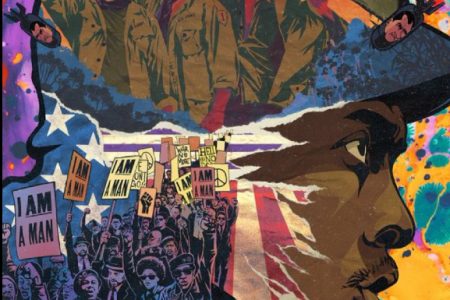

Four men walk into a room on a night in February 1964, unaware of how their shared – and distinct – legacies will come to define the best half century in American history.

I’m not sure I’ll see an opening-credits sequence this year at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) that’s better than that of “Akilla’s Escape”.

This year, with the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting the film industry, a smaller slate of films has been rolled out for the virtual TIFF 2020.

If viewed as an allegory, or as a film with any philosophical profundities to offer about the world, “The Burnt Orange Heresy” seems to collapse before our eyes.

In “How to Build a Girl”, Johanna Morrigan is a teenaged girl who reinvents herself as a worldly music critic, Dolly Wilde, complete with red hair and a scathing penchant for tearing down musicians.

In “Summerland”, Alice Lamb is entrusted with the care of a young boy seeking safety from his London home in her Kent cottage during the height of World War II.

The social and cultural implications of the present pandemic are so incisive, it feels impossible not to see it in any media that we consume.

Ambition is a tricky thing. On its face, the word, which means “a strong desire to do or achieve something,” is innocuous.

There is scene that comes a little over halfway into “Never Rarely Sometimes Always”, where director/writer Eliza Hittman reveals the meaning and value of the film’s title in one of the most searing moments in cinema of 2020.

Max Barbakow’s directorial debut is another entry in the long line of media about time loops.

It makes sense that the very best of “Miss Juneteenth” seems to emanate from the warm, but unflappable gaze of Nicole Beharie.

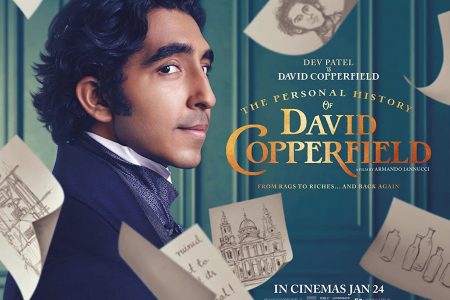

In “The Personal History of David Copperfield”, Armando Iannucci’s adaptation of Charles Dickens’ bildungsroman paints the varied locales of Victorian-era England with strokes of playful whimsy that bleed into its mood and form.

Every interaction of our lives is affected by the weight and history of things that came before – our politics, our forefathers, exigencies of power, the meeting points of class, race and gender.

Before the North American premiere of “Wasp Network” at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) last year, director Olivier Assayas appeared to introduce the film to the audience.

It’s anyone’s guess what the film industry, local and international, will look like whenever the world comes out on the other side of the current pandemic.

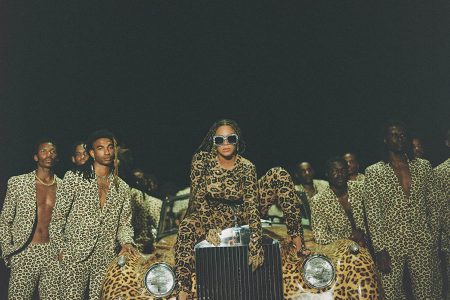

What does it mean for art to become political? The question occurred to me this past week watching the way protests against anti-blackness spilled out from the USA to the rest of the world after police killed yet another black life.

The ePaper edition, on the Web & in stores for Android, iPhone & iPad.

Included free with your web subscription. Learn more.