Rethinking the relationship with Europe

Today, October 1, the European Union’s sugar regime, which has for decades sustained the production of cane and raw sugar in the Caribbean, comes to an end.

Today, October 1, the European Union’s sugar regime, which has for decades sustained the production of cane and raw sugar in the Caribbean, comes to an end.

Earlier this year, the Commonwealth Marine Economies Programme published a report on the impact of climate change on Caribbean Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

In an age when most in the business of tourism are seeking to increase their income by selling authenticity to millennials and baby-boomers, it is perhaps puzzling that another rapidly growing industry segment now wants to deliver just the opposite.

A year from now, negotiations will begin for a successor agreement to the Cotonou Convention.

As the year proceeds, Mexico, the world’s thirteenth largest economy, is expected to rebalance its international trade relationships.

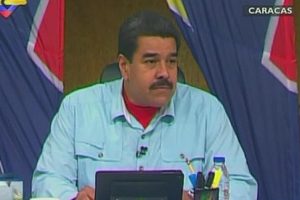

Having established a constituent assembly able to rewrite the Venezuelan constitution, take essential political and economic decisions, and confirm key appointments, President Nicolás Maduro’s government is now moving swiftly to assert its overall authority.

Speaking on August 11, at a press conference at one of his golf courses, the US President, Donald Trump, scored the equivalent of a foreign policy own goal.

Historically Caribbean railways existed to carry cane to factories, or raw sugar and molasses to ports.

When it comes to valuing tourism’s economic contribution, most Caribbean governments share publicly only arrival numbers and the country of origin of their visitors.

By any measure, the Caribbean’s infrastructure requirements are substantial. If the region is to be able to increase its competitiveness and give citizens the quality of life they desire, its transformation has become a matter of urgency.

Last month a report appeared indicating just how important one of the Caribbean’s overseas territories has become in facilitating global trade.

There is a pervasive view within and beyond the Caribbean that the regional integration process is foundering, and that its progress is being held back by an absence of political compromise and a failing bureaucracy.

According to speakers at the recently held Chicago Forum on Global Cities, nearly four fifths of future growth is likely to come between now and 2030, from urban centres with over 0.5 million people.

Last month, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) produced a worrying “situational update” on the implications of the accelerating numbers of Venezuelans arriving in Trinidad, Brazil and Colombia.

On June 16, speaking in Miami, President Trump announced measures reversing aspects of his predecessor’s policy of normalising relations with Cuba.

A little over a week ago, the British people went to the polls.

A few days ago, China struck a remarkable deal: it agreed with the state of California to work on projects that will help lower US greenhouse gas emissions.

For the Caribbean, climate change and its mitigation is like no other issue: it is existential.

When the former US President, Barack Obama, announced in late 2014 that he was easing travel restrictions on US citizens wishing to visit Cuba, a frisson ran through the tourist industry in the rest of the region.

A few days ago, the Prime Minister of Jamaica, Andrew Holness, and the President of the Dominican Republic, Danilo Medina, agreed to work towards a closer relationship.

The ePaper edition, on the Web & in stores for Android, iPhone & iPad.

Included free with your web subscription. Learn more.