Oil, Government Take & Spending: Navigating Guyana’s Development Challenges – 19

Introduction Today’s column concludes my overall assessment and evaluation of Guyana’s Green Paper on its proposed Natural Resources Fund (NRF).

Introduction Today’s column concludes my overall assessment and evaluation of Guyana’s Green Paper on its proposed Natural Resources Fund (NRF).

Introduction Today’s column continues to advance my overall assessment/evaluation of Guyana’s Green Paper, which proposes to establish a Natural Resources Fund (NRF) next year.

Introduction Today’s column is numbered 16 in the sequence devoted to evaluating the “top-10 development challenges” that I predict spending Guyana’s Government Take from the coming petroleum sector has to navigate.

Introduction Today’s column starts my evaluation of the Green Paper on Guyana’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF), laid by the Government of Guyana (GoG) in the National Assembly on August 8th, 2018.

SWFs &Global Capital Circuits Today’s column revisits my earlier discussion (January 8 to February 5, 2017) of Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs).

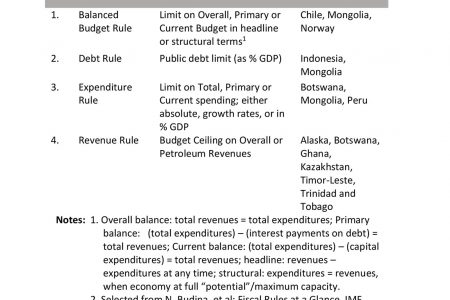

Introduction Today’s column considers the challenge of navigating external pressures on Guyana to pursue a spending path for its expected Government’s Take, which conforms with what economists term the “permanent income hypothesis (PIH) budget rules”.

Introduction Today’s column starts with a wrap-up of the discussion on intergenerational equity.

Wrap-up: Implementation Lags As promised last week, today’s column first indicates the main lessons to be learnt from other developing countries’ experiences in dealing with implementation lags when preparing for the coming on-stream of a relatively massive extractive petroleum sector such as Guyana’s.

Introduction: “Oil for Cash” This week’s column addresses the development challenge posed by implementation lags.

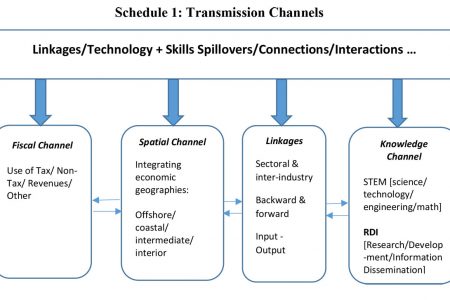

Introduction This week, I conclude my discussion on the requirements for avoiding the perils of enclave-type development in Guyana’s economic structures.

Introduction Today’s column wraps-up my consideration of absorption capacity. This is the fourth on the list of top-ten development challenges, which spending Guyana’s expected significant Take (petroleum revenues) has to navigate in coming years in order to achieve sustained development.

Introduction Today’s column continues the discussion on absorption capacity. This is on my list of top-ten development challenges, which spending of Guyana’s expected significant Government Take from first oil and first gas will have to contend with, starting 2020.

Introduction Today’s column starts my discussion of the fourth of the top-ten development challenges that spending of Guyana’s expected significant “Government Take” will have to navigate in the coming years of oil and gas production and export.

Introduction Because of the amount of material I still have left to cover and the usual space limitations, today’s column is confined towards advancing the discussion of the Governance Curse.

Introduction Today’s column wraps up my discussion of the Resource Curse.

Introduction Today’s column considers the second topic in my list of the top ten developmental challenges, which the spending of Guyana’s significant estimated Government Take from the petroleum sector must navigate.

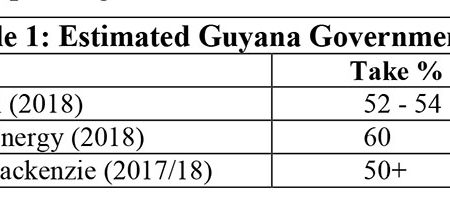

Introduction: Top Ten Last week’s column wrapped-up my evaluation of Open Oil’s financial modeling of Guyana’s 2016 Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) with the local ExxonMobil subsidiary and its partners.

Introduction Today’s column concludes the discussion of Open Oil’s modeling exercise of Guyana’s 2016 Production Sharing Agreement (PSA).

Today’s column continues with my critiques of Open Oil’s financial modeling of Guyana’s 2016 Production Sharing Agreement, PSA.

Introduction Today’s column continues with my critiques of Open Oil’s financial modeling exercise of the Guyana 2016 Production Sharing Agreement, PSA.

The ePaper edition, on the Web & in stores for Android, iPhone & iPad.

Included free with your web subscription. Learn more.