Appraising the local refinery option: Step 1 – Basic oil refinery economics

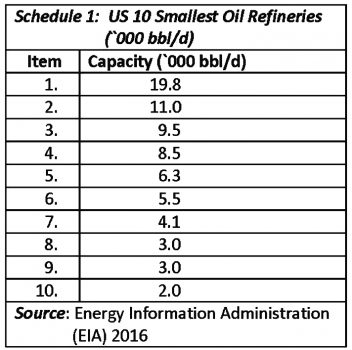

Introduction Today’s column addresses several economic factors which are key to the oil refinery business.

Introduction Today’s column addresses several economic factors which are key to the oil refinery business.

Introduction This week’s column and the next will attempt to evaluate the pros and cons of small mini-oil refineries.

Introduction My last column had introduced what is often deemed in the literature as the most fundamental observation related to oil refineries in energy economics.

Introduction Oil and natural gas industry analysts and energy economists repeatedly highlight the basic observation that no two oil refineries are the same; stressing that they are unique in essential ways.

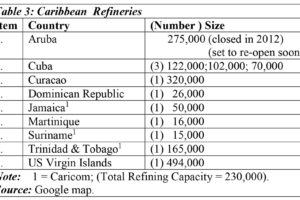

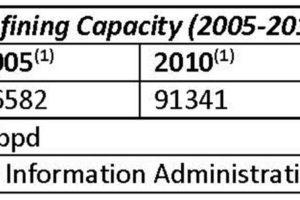

As repeatedly urged, readers need to be familiar with the basic structure/features of global oil refining, if they wish to make informed contributions towards Guyana’s first oil, particularly in view of the fact that a local refinery would likely contribute marginally (0.1 per cent) to global refining capacity.

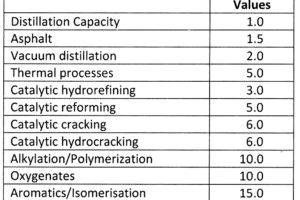

Introduction If one began with the standard industry description of an oil refinery that was earlier introduced, which is: “an industrial plant or complex that manages hydrocarbon molecules extracted from crude oil, natural gas liquids and national gas” (in the case of Guyana, at the Stabroek bloc Liza wells), that complex could produce an assemblage of different petroleum based products that can potentially reach several thousand.

Introduction Last Sunday’s column introduced several of what I labelled as nuts and bolts matters related to oil refining, of which I believe an informed Guyanese public needs to be aware.

Introduction In concluding last Sunday’s column (May 21), I had indicated that, starting today, I would offer commentary on the topic: establishing a local refinery to process Guyana’s expected production of crude oil, post-2020.

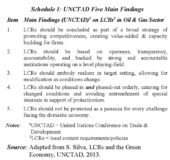

Today’s column starts with an offering of a few concluding comments on the topic considered over recent weeks: local content requirements/policies (LCRs) in the petroleum industry, as Guyana prepares for its own industry, scheduled to come on-stream post-2020.

Introduction My two previous columns (April 30 and May 7) were devoted to, respectively, the main findings of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) 2013, and the World Bank’s 2013 evaluation/research of the lessons to be learned from global experiences with local content requirements/policies (LCRs) in the oil and gas sector.

Introduction Today I provide my penultimate presentation on “lessons to be learned from global experiences with local content requirements (LCRs) for the oil and gas sector”.

Introduction There is a formidable body of literature devoted to economic theorizing on the efficacy of local content requirements (LCRs) policies generally, and in developing countries specifically.

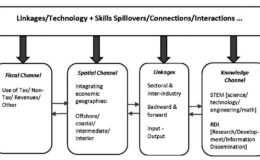

Introduction Today’s column continues the effort to provide for readers’ guidance a response to the burning question: What are the lessons to be learned from oil and gas producing countries that have implemented policies/regimes for local content requirements (LCRs)?

Introduction Last week’s column had indicated that, starting today, I would seek to draw lessons arising from global experiences with national local content requirement (LCR) regimes, which are aimed at maximizing economic benefits derived from the creation of export-oriented oil and gas extraction industries, based on significant domestic resource finds.

Introduction My aim has been in recent columns to lay out carefully the economic rationale in support of the proposition that, if Guyana’s coming oil and gas extraction industry is to play a transformative role in its economic development, then the dynamic integration of whatever economic benefits are derived from the industry into other economic sectors is essential.

Introduction In last week’s discussion of Guyana’s proposed local content requirements (LCRs) policy for its coming oil and gas extraction industry, I had introduced three key concepts, which require further elaboration.

Introduction In my New Year’s Day column this year I had indicated there are three policy priorities which seemingly guide government’s preparations for the development of its impending oil and gas-based extraction sector.

Introduction Today’s column concludes discussion on the institutional aspects of Guyana’s preparations for its coming petroleum industry.

Introduction At the conclusion of last week’s column, I had indicated the intention to wrap up in today’s column my discussion concerning the institutional architecture and governance in preparation for Guyana’s coming gas and oil industry.

Introduction Last week’s column advanced the view that Guyana’s membership of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a crucial plank in the institutional governance architecture being designed for managing its impending oil and gas extraction industry.

The ePaper edition, on the Web & in stores for Android, iPhone & iPad.

Included free with your web subscription. Learn more.